(Continued from Part I)

The Survival of Paganism at Harran

Late in the 9th century, the Harranian Pythagorean Thabit ibn Qurra was invited to found a Sabian school at the Bayt al-Hikmah in Baghdad. Thabit was adamantly Pagan, but maintained his position as an advisor to the caliph, even when making statements at the caliph’s court like:

Paganism, which used to be the object of public celebration in this world, is our heritage, and we shall pass it on to our children. Lucky the man who endures hardship with a well-founded hope for the sake of paganism! Who was it that settled the inhabited world and propagated cities, if not the outstanding men and kings of paganism? Who applied engineering to the harbors and the rivers? Who revealed the arcane sciences? Who was vouchsafed the epiphany of that godhead who gives oracles and makes known future events, if not the most famous of the pagans? It is they who blazed all these trails. The dawn of medical science was their achievement: they showed both how souls can be saved and how bodies can be healed. They filled the world with upright conduct and with wisdom, which is the chief part of virtue. Without the gifts of paganism, the earth would have been empty and impoverished, enveloped in a great cloud of destitution (Fowden 1993: 64-65).

Note: The word translated as “pagan” is the Syriac word hanputho. Tamara M. Green, Professor of Classical and Oriental Studies at Hunter College (City University of New York) and one of the world’s leading authorities on Harranian religion, also reproduces this passage, but she leaves hanputho untranslated. After the quoted passage, Green notes…

‘We are the heirs and transmitters of hanputho,’ Thabit declared, and although this Syriac word, like its Arabic cognate, hanif, is often translated as ‘pagan’ when applied to preislamic religions, it may also have here the same meaning as hanif seems to be given in the Qu’ran: ‘a possessor of the pure religion.’ … it is not improbable that Thabit, familiar with Muslim doctrine, could have used this word purposefully because of its Qu’ranic associations with Abraham, in order to provide the link between the first hanif and Sabian ‘heirs and transmitters’ at Harran (Green 1992: 114).

Green continues with a lengthy discussion of the Arabic word hanif and the cognate Syriac word hanputho, noting that al-Biruni (d. 1050 CE) reports in his Chronology of Nations that before the Harranians were known as Sabians “they were called hanifs, idolators and Harranians” (Green 1992: 116). While hanputho and hanif had somewhat different meanings, the words were indeed related, used interchangeably with “Sabian”, and applied to pagans.

In the 10th century, the amir ‘Adud al-Dawlah issued an “edict of toleration” specifically permitting the traditional rites of Harranian Pagans.

In the 11th century, after the Muslim conquest of North Africa and Spain, the Ghayat al-Hakim (“Aim of the Sage”), a book known in Latin as the Picatrix, was written in Spain by “al Majriti” (Pingree 1980; 1986). Considered the basis of the grimoire tradition of Europe (including material that survives down into the Books of Shadows of certain modern Craft traditions), the Picatrix includes significant material about the religion and rites of the Harranians. This same “al Majriti” is also our source for the Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa (“Epistles of the Brethren of Purity”), a mystical Muslim order incorporating teachings from Neoplatonic, Hermetic, and even Buddhist sources (Netton 1991). Both books contain material from each other and have a Harranian source (Nasr 1993: 25-104). Whether “al Majriti” was himself a Harranian Sabian is unknown.

David Pingree has pointed out that many of the Greco-Roman magical texts evident in the Picatrix passed into Arabic by way of Sanskrit, picking up Indian magical terms and Sanskrit names for the Gods along the way (Pingree 1980). Truly, Harran deserved the name “crossroad”.

The Last Days of Harran and the Return of Paganism to Europe

Later in the 11th century, 1081 CE, the Temple of the Moon God was finally destroyed by al-Shattir, an ally of the Seljuk Turks, contemporaneous with the rise of Ash’arism (Green 1992: 98-100). At this point, the “con-job” story became the “official” Muslim view. Also late in the 11th century, c. 1050 CE, the Christian writer Michael Psellus, studying in Constantinople, received an annotated copy of the Hermetica from a scholar from Harran. It is quite possible that these were sacred texts that had escaped the decline and ultimate destruction of the temples (Scott 1982: 25-27, 108-109; Copenhaver 1992: xl; Faivre 1995: 182). Copies of the Hermetica eventually made their way to Western Europe, igniting the interest of Cosimo de’Medici who, in 1462, set a young Marsilio Ficino to the task of their translation. Thus began Europe’s fascination with the Hermetica (Copenhaver 1992: xlvii-l; Faivre 1995: 30, 38-40, 98), a fascination that would help fuel the Renaissance.

During the First Crusade, Harran was often contrasted with its neighbour to the north, Edessa (known today as Urfa). Edessa was the birthplace of the prophet Abraham and the first city to convert to Christianity (Segal 1970: 60-81). Edessa converted after its king, Abgar, wrote to Jesus requesting healing. The apostle Thaddeus came with a cloth bearing the image of Jesus’ face. Abgar was healed and his kingdom converted. The cloth, known as the Mandylion, was an important relic during the Crusades (Segal 1970: 215; Wilson 1998: 161-175). (Recently discovered documents have led some to believe that it is the same cloth that later came to be called the Shroud of Turin.)

In the 12th century, Edessa was the capital of the short-lived Crusader County of Edessa. The Crusaders occupying the city were described as “roaming about the countryside at will”. Their presence might explain an unusual architectural feature that survives at Harran.

In Harran’s Citadel , there is a Christian chapel of Crusader architecture (Lloyd & Brice 1951: 102-103). There is no record of any Crusaders ever conquering the city (Segal 1970: 230-251; Green 1992: 98; Gunduz 1994: 133). The presence of the chapel would appear to indicate a peaceful Crusader presence. The fact that the chapel is side-by-side with the Citadel’s mosque, even sharing an entry hall, is even more striking. It was far more common for chapels and mosques of that time to be built on top of each other or to be co-opted one from the other. Is this another example of the city’s remarkable religious tolerance?

This chapel contains another interesting feature: a floor of black basalt brought from hundreds of miles to the East, which is found in only one other place at Harran. The floor of the temple of the Moon God (currently under the remains of the Grand Mosque) is of the same black basalt construction. Muslim accounts have always referred both to a temple of the Moon God under the Grand Mosque and to one in the Citadel (Lloyd & Brice 1951: 96; Gunduz 1994: 204; Kurkcuoglu 1996: 17). The black basalt floor under the Crusader chapel suggests these Crusaders, whoever they were, built their chapel on top of the Citadel’s Moon God temple.

Christian writers at Edessa delighted in contrasting itself, the first Christian city, known as “the Blessed City”, with Harran, the last Pagan holdout, called “Hellenopolis”. Unfortunately, Edessa is higher up the water table from Harran. As Christian Edessa grew and prospered it sank more and more wells, gradually drying up the wells of Harran, inlcuding the Well of Abraham.

Finally, in 1271 CE, the Mongols conquered the area around Harran. They decided that Harran was too much trouble to control (they would probably open their gates to the next army to come along), too remote to garrison, but too valuable to destroy. They arrived at an unusual and dramatic solution.

They deported the populace of the city, walled up the city gates, and left it.

There is no record of the city being destroyed, sacked, burned, or in any other way damaged. The space enclosed by the city walls gradually filled up with wind-blown dirt.

Since that time, only three parts of Harran have been kept relatively clear of covering soil. The Citadel at the south end of the city and the central tumulus in the center are on hills and so remained above the accumulated debris. The area of the first Islamic university (and its Grand Mosque) have been kept clear by human effort because of its historical and religious significance to Muslims.

It is widely believed that the university area also contains the site and remains of the Temple of the Moon God. The discovery at this place about 10 years ago by Dr. Nurettin Yardimci of three stela erected by Nabonidus in the 5th century BCE and dedicated to Sin seem to confirm this.

Everything else is about thirty feet below the current ground level. It is difficult to over-estimate the treasure-trove of artefacts and knowledge waiting to be uncovered.

A Treasure Waiting to be Uncovered … or Destroyed

The most recent archaeological information on Harran can be found in three articles published in issues of Anatolian Studies by Seton Lloyd and William Brice in 1951 and by D.S. Rice in 1952. These expeditions confined themselves to surveying the site and clearing the rubble from in front of one of the city gates.

H.J.W. Drijvers, author of Cults and Beliefs at Edessa, visited Harran sometime in the 1970s, and Tamara Green, author of The City of the Moon God, visited Harran in 1977, but both confined themselves to observing the discoveries previously reported and did not uncover any new material.

Nurettin Yardimci has headed a small but meaningful effort at Harran, doing restoration work on buildings that were falling down and working with a Belgian team to excavate the Roman-period dwellings on the central tumulus, but this effort had to be suspended in the mid-90’s after only a couple of seasons due to Kurdish violence (Bucak 1998: pers. comm.). The results of the tumulus dig have not yet been published.

It is surprising that Harran remains virtually untouched.

When Anna and I met with Eyyup Bucak, the Director of the Museum in Urfa in 1998, he was clearly greatly concerned over the amount work to be done in his area and the little time remaining in which to do it. He explained that the Turkish government was engaged in what was (and is) called the GAP project, a dam across the Euphrates that would provide water for irrigating the Harran Plain. The rising waters behind the dam would eventually cover six important Neolithic sites. Accordingly, rescue archaeology was underway at a furious pace. This was taking all available funding and energies. While Dir. Bucak said that he would welcome foreign interest in Harran, the Turkish government’s regulations make it very difficult for foreign archaeologists to work in Turkey. Turkey has a long history of their archaeological treasures being plundered by foreigners and is understandably wary.

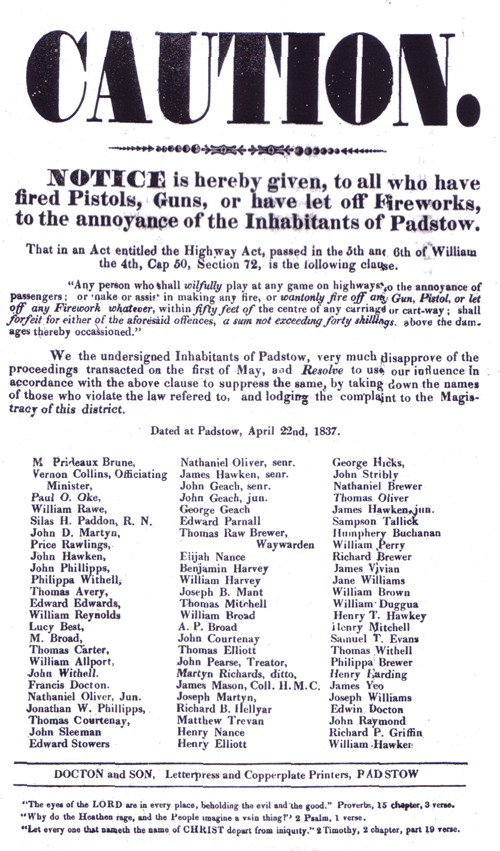

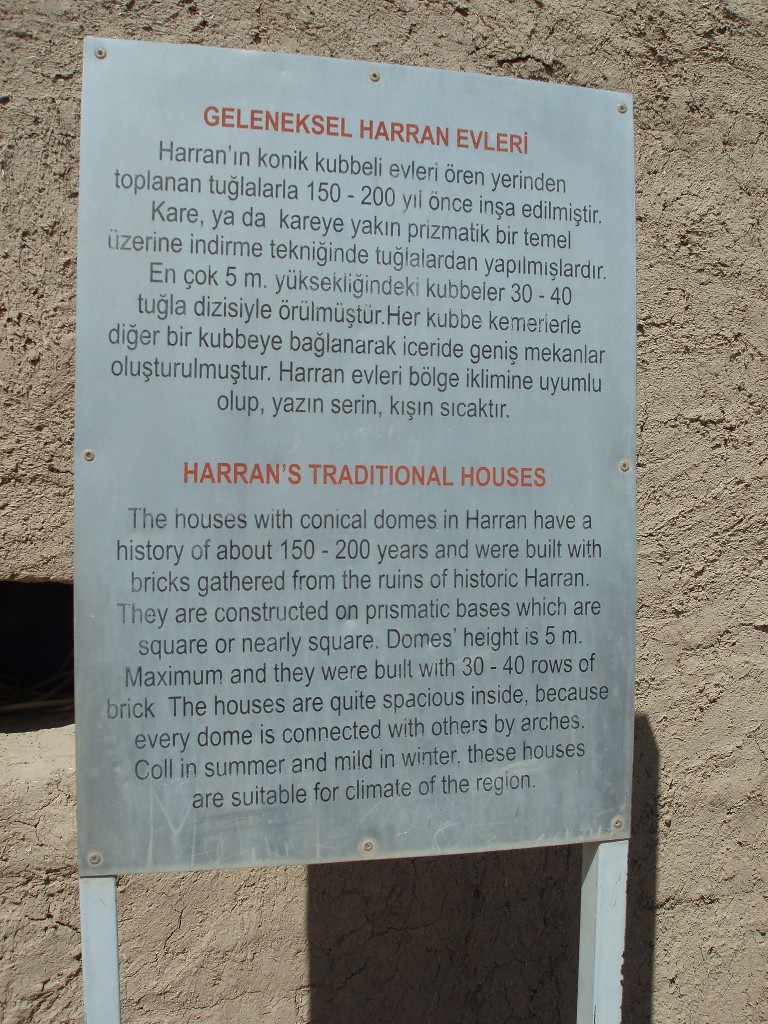

The primary purpose of the GAP project is bringing irrigation to the Harran Plain. Irrigation means crops; crops means farmers; farmers mean settlement. When Lloyd, Brice, and Rice visited Harran in the 50’s, only a few of the “distinctive beehive huts” of the local nomads could be found in the filled-in area inside the old city walls. Now, permanent houses are being built there. Turkey does not exercise “eminent domain” over archaeological sites. Whatever is under a house is lost forever.

(You can see the rapid growth in irrigation and farming online at http://www.fas.usda.gov/pecad/highlights/2002/10/turkey/images/Landsat_Harran.htm)

In 1998, Anna and I also met with two professors of Islamic theology from the local University of Harran at Urfa, Dr. Mustafa Ekinci and Prof. Kamil Harman. Dr. Ekinci is a specialist in esoteric movements in Islam. When I explained my interest in early Muslim and pre-Muslim esoteric movements at Harran, they not only professed ignorance of the subject, but actively disapproved of my studying it. The Ash’arite view of the Harranians prevails and contributes to a lack of interest in excavating Harran. (And when the topic drifted into them inquiring about our own religious beliefs … the evening got interesting and we sorely taxed the abilities of our able translator.)

Harran was a thriving Mesopotamian and later Hellenistic city of some 10 to 20,000 people for nearly 3000 years. Towards the end, for about 500 years, Harran would appear to have been a kind of intellectual refugee camp for educated members of the mystery cults of late antiquity, eventually becoming the font from which Hermetic and Neoplatonic learning returned to Europe.

Many of the Pagans of Harran had fled the triumph of Christianity in the West. All of them, including the practitioners of the indigenous Moon cult, were surrounded by an ever-expanding Islam. The Pagan community of Harran must have lived with a constant awareness of being the last refuge of the old Pagan religions. These “Pagan refugees” would have had every reason to preserve their traditions for future generations. Some were Mithraists, well aware of the concept of turning cycles of ages. Others would have known that their own sacred texts, the Hermetica, predicted the fall of Paganism, and its eventual return.

Ibn Shaddad, who wrote a financial inspection report on Harran in 1242 CE, only twenty-nine years before its demise, described cisterns feeding public fountains, four madrasas (theological colleges), two hospices, a hospital, two mosques (in addition to the Grand Mosque), and seven public baths. In addition to these, Ibn Jubair, who visited the city in 1184 CE described “the city’s flourishing bazaars, roofed with wood so that the people there are constantly in the shade. You cross these suqs as if you were walking through a huge house. The roads are wide and at every cross-road there is a dome of gypsum” (Rice 1952: 36-39).

Harran was the last haven of Mediterranean Paganism up until the 11th century… only 800 years ago. It was never destroyed, it was never sacked, and it was never dug up by treasure hunters. It was just abandoned and allowed to fill in with dirt. And it has never been excavated. It is not difficult to imagine that under some 30 feet of wind-blown sand and dirt, the heritage of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Paganism is just waiting, intact, for someone to dig it up.

But they’ll have to hurry …

Another effect of the GAP project, and its attendant increased irrigation, is that the water table of the Harran Plain is once again rising. Whatever treasures are waiting underground, whatever documents survive (and the Museum at Urfa believes there are likely to be many), will soon be below the water table. The city walls will act as a coffer-dam for a while, but in about 15 years whatever documents from antiquity lie untouched a few yards down at Harran will be lost forever.

I hope that an increased awareness of Harran’s history as a crossroads of cultures and religions, its significance for the transmission of the knowledge of antiquity into Islam and the West, its example for our times of peaceful relations between Pagans and Muslims, and the tremendous potential for the recovery of lost knowledge in the form of surviving texts will lead to the necessary excavation and preservation and study of this site.

I fully expect the final unveiling of Harran to rival Pompeii in the splendor and value of its contents.

Recommended Books & Articles on Harran & Harranian Religion:

(Note: I am indebted to Brandy Williams for first making many of these texts available to me and for sharing the fruits of her own extensive research on the subject.)

al-Biruni, The Chronology of Ancient Nations, trans. & ed. by C. Edward Sachau, Hijra International Publishers, Lahore, Pakistan, 1983

Ali, Abdullah Yusuf, trans., The Holy Qur-an: English translation of the meanings and Commentary, The Custodian of The Two Holy Mosques King Fahd Complex For The Printing of The Holy Qur-an, al-Madinah, 1405 AH

Athanassiadi, Polymnia, “Persecution and Response in Late Paganism: The Evidence of Damascius”, in The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Volume CXIII, The Council of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, 1993

—————————-, and Michael Frede, eds., Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1999

Betz, Hans Dieter, ed., The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation (including the Demotic Spells), 2nd (revised) edition, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992

Bucak, Eyyup, personal communication, January 7, 1998

Chuvin, Pierre, A Chronicle of the Last Pagans, HarvardUniversity Press, CambridgeMA, 1990

Chwolson, D., Die Ssabier und der Ssabismus (2 vols.), Oriental Press, Amsterdam, 1965

Copenhaver, Brian P., trans. and ed., Hermetica, CambridgeUniversity Press, 1992

Crowther, Patricia, Witch Blood!, House of Collectibles, Inc., New York, 1974

Drijvers, H.J.W., “Bardaisan of Edessa and the Hermetica: The Aramaic Philosopher and the Philosophy of His Time”, in Jaarbericht van het Vooraziatisch-Egyptisch, Genootschap Ex Oriente Lux 21, Leiden, 1970 (Bardaisan was a Hermeticist at nearby Edessa)

——————-, Cults and Beliefs at Edessa, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1980

——————-, “The Persistence of Pagan Cults and Practices in Christian Syria”, in Garsoïan, Nina, et al., ed., East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the Formative Period (Dumbarton Oaks Symposium, 1980), Dumbarton Oaks, WashingtonD.C., 1982

Faivre, Antoine, The Eternal Hermes: From Greek God to Alchemical Magus, Phanes Press, Grand Rapids, 1995

Fowden, Garth, Empire to Commonwealth: Consequences of Monotheism in Late Antiquity, PrincetonUniversity Press, PrincetonNJ, 1993

Gardner, Gerald B., Witchcraft Today, Rider & Company, London, 1954

———————–, The Meaning of Witchcraft, The Aquarian Press, London, 1959

Gimaret, D., “Shirk”, in Encyclopaedia of Islam CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0, Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999, vol. IX, p. 484b-485b

Godwin, Joscelyn, Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival, Phanes Press, Grand Rapids, 1993

Green, Tamara, The City of the Moon God: The Religious Traditions of Harran (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, Volume 114), E.J. Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992

Gündüz, Şinasi, The Knowledge of Life: The Origins and Early History of the Mandaeans and Their Relation to the Sabians of the Qur’an and to the Harranians, (Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement 3), OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford, 1994

Hammer-Purgstall, Joseph, tr., Ancient Alphabets and Hieroglyphic Characters Explained (translation of Ibn Wahshiya’s “The long desired Knowledge of occult Alphabets attained.”), W. Bulmer, London, 1806

Hassan, Selim, Excavations at Giza, Goverment Press, Cairo, 1946

Ilsetraut Hadot, “The Life and Work of Simplicius in Greek and Arabic sources”, in Sorabji, Richard, ed., Aristotle Transformed: The Ancient Commentators and Their Influence, Gerald Duckwoth & Co., London, 1990

Islam, Khawaja Muhammad, Narratives of the Prophets, Farid Book Depot (Pvt.) Ltd., Delhi, 1999

Kurkcuoglu, A. Cihat, Harran: The Mysterious City of History, Harran Koylere Hizmet Goturme Birligi, Anakara, 1996

Lewy, Hans, Chaldaean Oracles and Theurgy: Mysticism, Magic, and Platonism in the later Roman Empire, Etudes Augustiniennes, Paris, 1978

Lloyd, Seton, and William Brice, “Harran”, in Anatolian Studies, Vol. I, pp. 77-111, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, Ankara, 1951

Majercik, R.T., The Chaldean Oracles (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, Volume 5), E.J.Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, 1989

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, “A Panorama of Classical Islamic Intellectual Life” and “Hermes and Hermetic Writings in the Islamic World”, in Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, Islamic Life and Thought, State University of New York Press, Albany NY, 1981

—————————, An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1993

Netton, I.R., Muslim Neoplatonists: An Introduction to the Thought of the Brethren of Purity, EdinburghUniversity Press, Edinburgh, 1991

Nock, Arthur Darby, ed. & trans., Sallustius: Concerning the Gods and the Universe, CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge, 1926

Pingree, David, “Some of the Sources of the Ghayat al-Hakim”, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Volume 43, pp. 1-15, The Warburg Institute, London, 1980

——————, ed., Picatrix: The Latin version of the Ghayat Al-Hakim, The Warburg Institute, London, 1986

——————, “The Sabians of Harran and the Classical Tradition”, in International Journal of the Classical Tradition, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2002

Prag, Kay, “The 1959 Deep Sounding at Harran in Turkey”, in Levant: Journal of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, Vol. II, pp. 63 – 94, The British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, London, 1970

Remes, Pauliina, Neoplatonism, Ancient Philosophies #4, University of California Press, BerkeleyCA, 2008

Rice, D.S., “Medieval Harran: Studies on its Topography and Monuments”, in Anatolian Studies, Vol. II, pp. 36-84, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, Ankara, 1952

Ross, Steven, K., Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire, 114 – 242 CE, Routledge, London and New York, 2001

Scott, Walter, ed. & trans., Hermetica: Introduction, Texts and Translation, Hermes House, Boulder CO, 1982

Segal, Judah Benzion, “Pagan Syriac Monuments in the Vilayet of Urfa”, in Anatolian Studies, Vol. III, pp. 97 – 119, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, Ankara, 1952

————————–, “The Sabian Mysteries: The Planet Cult of Ancient Harran”, in Vanished Civilizations of the Ancient World (Edward Bacon, ed.), Thames and Hudson, London, 1963

————————–, Edessa: “The Blessed City”, OxfordUniversity Press, Oxford, 1970

Shaw, Gregory, Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus, PennsylvaniaStateUniversity Press, University ParkPA, 1995

Smith, John Holland, The Death of Classical Paganism, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1976

van der Meer, Annine, “The Harran of the Sabians in the First Millennium A.D.: Cradle of a Hermetic Tradition?”, presented at the session on Western Esotericism and Jewish Mysticism at the IAHR congress in DurbanS.A., 2000

Wallis, R.T., Neoplatonism, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1972

Walbridge, John, “Explaining Away the Greek Gods in Islam”, in Journal of the History of Ideas 59.3, 1998

——————–, The Wisdom of the Mystic East: Suhrawardi and Platonic Orientalism, SUNY Press, AlbanyNY, 2001

Wilson, Ian, The Blood and the Shroud, The Free Press, New York, 1998

Yardimci, Nurettin, “Excavations, Surveys and Restoration Works at Harran”, in Frangipane, M. et al, eds., Between the Rivers and Over the Mountains: Archaeologica Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri Dedicata, Universita di Roma, Rome, 1993

Zimmern, Alice, Porphyry’s Letter to His Wife Marcella: Concerning the Life of Philosophy and the Ascent to the Gods, Phanes Press, Grand Rapids, 1986

See the Photo Gallery.