Sommige artikelen in Wiccan Rede Magazine waren niet alleen heel goed op het moment dat ze werden gepubliceerd, maar hebben sindsdien hun waarde behouden. De meeste lezers van Wiccan Rede Online hebben deze artikelen nooit kunnen lezen, wat jammer is. In deze categorie, Tijdloze Teksten, publiceren we een aantal van dit soort artikelen opnieuw.

Dit artikel werd geschreven voor het nummer Samhain 2006 van Wiccan Rede, door Merlin, die mede-oprichter was van Silver Circle en lang hoofdredacteur was van Wiccan Rede.

* Het beeldmerk ‘Hot items’ stond voor dit type artikelen:

Een diepgaande bespreking van controversiële onderwerpen, en van verschillen tussen de wicca als inwijdingstraditie en de solo-hekserij.

Er ligt een behoorlijk hoge drempel tussen het lezen over wicca, en ook daadwerkelijk je eerste ritueel uitvoeren. Meestal kiest men dan om bestaande gepubliceerde rituelen te gaan uitvoeren. Maar juist dan bestaat het risico dat het een toneelstukje blijft, dat het te weinig aansluit op je eigen ervaringswereld. Maar hoe kan dat dan anders?

Als je voor het eerst een ritueel uit wilt gaan voeren komt er een hele grote berg vragen en problemen op je af. Vragen rondom de datum en tijd van het ritueel. Waar moet je het uitvoeren, thuis, of in de vrije natuur? Hoe zit het met huisgenoten, de telefoon, of met toevallige passanten in de natuur? Of misschien voel je je niet veilig buiten in het bos, of héb je helemaal geen bos in de buurt? Vragen over het ritueel zelf, de tekst, invocaties, muziek. Vragen over de aankleding, moet het skyclad of in een gewaad of in gewone kleding? Vragen over de kleuren van de kaarsen, over de positie van het altaar, over het formaat van de cirkel, over de ingrediënten in de wierook. En nog veel meer. Een gigantische waslijst van dingen, waarvan je je ineens realiseert dat je ze eigenlijk zou moeten weten voordat je aan een ritueel begint. En vaak genoeg zie je door de bomen het bos niet meer en komt de tijd van het ritueel naderbij, en glijdt voorbij, zonder dat je het ritueel ook uitvoert. Je keert terug naar de gemakkelijke leunstoel en het volgende boek, wetend dat je nog zoveel meer moet leren voordat je ook de praktijk in kunt duiken…

De oplettende lezer heeft echter in het bovenstaande misschien iets opgemerkt. Het gaat allemaal om dingen, om fysieke voorwerpen of fysieke omstandigheden, om praktische punten. De vraag wat een ritueel is, wat een ritueel beoogt, waarom je het uit zou voeren, hoe een ritueel in elkaar zit, die vragen worden niet gesteld. En de beginner stelt zich die vragen meestal ook niet. Het loopt zo tegen de herfstequinox of tegen Samhain, je wilt ‘iets’ gaan doen, en zoekt een geschikte rituele tekst op. En daarmee is het inhoudelijke deel meestal opgelost, uitgezocht, klaar, afgedaan.

Met de keus voor een bestaand ritueel, neem je natuurlijk ook de keus van de schrijver over voor een bepaald thema, een focus. En je neemt ook alle praktische zaken over die onderdeel zijn van de vormgeving van het ritueel. En dan loop je dus tegen alle vragen aan die hierboven zijn genoemd.

Je kunt het geheel echter ook helemaal omkeren. Je kunt ook beginnen met je eigen antwoord op vragen rondom de functie van een ritueel, de thematiek, de vormgeving, en op die manier iets samenstellen dat én eenvoudig is, én aansluit bij je eigen ideeën, én praktisch uitvoerbaar, én bovendien goed werkt. Dat je dat niet vanzelf kunt spreekt voor zich, dit artikel wil aan de hand van een voorbeeld laten zien hoe je zoiets voor elkaar krijgt. Het wil als het ware een soort algemene rode draad aanreiken, waar je zelf mee aan de slag kunt.

Laten we maar bij de allermoeilijkste vraag beginnen. Want als je die niet kunt beantwoorden, is de rest eigenlijk zinloos. Die vraag is wat de functie van een ritueel is. Wat wil je bereiken? Waar is het voor? Waarom zou je een ritueel willen doen? Wat is het nut? Wat is de essentie van een ritueel? Wat voor invloed heeft het op jou? En nog veel meer vragen zou je kunnen stellen rond dit centrale thema, de vraag naar het ‘waarom’.

Er zijn heel veel antwoorden mogelijk, en ofschoon lang niet alle mogelijke antwoorden ook zinvol zijn, zijn er best veel verschillende invalshoeken te bedenken. Sommige antwoorden liggen voor de hand.

Eén zo’n antwoord is de behoefte om uitdrukking te geven aan jouw gevoel van verbondenheid met de wicca en met de goden, door middel van een ritueel. Meestal is dit geen intellectueel-beredeneerd motief maar een gevoelsmatig motief, je voelt je geroepen om een ritueel te doen, het trekt aan je, je voelt dat je op de een of andere manier op zoek bent naar een vorm van direct contact dat verder gaat dan ‘erover lezen’, en een ritueel ligt dan het meeste voor de hand. Sleutelwoorden zijn contact, verbondenheid, warmte en gevoel. Het is de pure religieuze instelling – het woord religie stamt af van het Latijn voor ‘verbinden’ – en je zoekt hier het contact met het goddelijke, en met de stroming als geheel.

Een andere mogelijke invalshoek is je behoefte aan inzicht, kennis of informatie. Misschien zit je met een probleem, met levensvragen, met twijfels, en kom je er via de normale wegen niet uit. Dan zoek je naar antwoorden vanuit de hogere werelden, antwoorden van de goden, naar inzichten die je leven in een bepaald perspectief zetten, zodat je een betere keus zult kunnen maken.

Sleutelwoorden zijn hier dus inzicht, informatie, perspectief, koersbepaling. Dit is het voorstadium van het stuk uit de wicca dat ‘hekserij’ wordt genoemd, het actief ingrijpen in het leven van jezelf of anderen. Dat actieve ingrijpen moet gebaseerd zijn op een goed en helder spiritueel inzicht, en het verkrijgen van dat inzicht kan een legitiem doel zijn in je rituelen.

Nog een mogelijke invalshoek voor een beginner om rituelen te willen gaan doen, is om direct te gaan toveren, magie te bedrijven enzovoort. Laat ik met een understatement maar zeggen dat we het daar niet over zullen hebben in dit artikel ☺ Maar het voorwerk, de voorstudie, de basiskennis die je nodig hebt om later magisch werk te kunnen doen, dat is inzicht in je eigen levensloop, en in de levensloop van anderen, in de wetmatigheden die daarin werkzaam zijn, en dáár kun je wel degelijk nu al mee aan de slag.

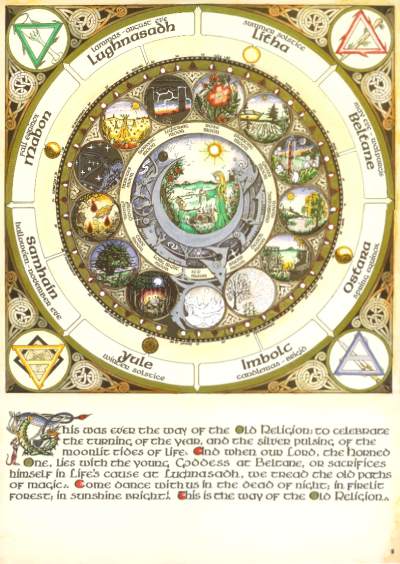

En nog een invalshoek tot slot, is de behoefte om de jaarcyclus te vieren, de gebeurtenissen in de natuur om je heen. Een volle maan, of een seizoen. Ook hier het aspect van verbondenheid, van het innerlijk willen meebeleven van de dingen die om je heen in de natuur gebeuren.

Als ik de voorgaande punten samenveeg, gaat het dus om de emotionele behoefte om een ritueel te vieren om in contact te komen met de goden, en/of gaat het om spiritueel inzicht of spirituele leiding, en/of gaat het om het vieren van verbondenheid met de natuur om je heen.

Er zijn allerlei manieren om deze drie aspecten vorm te geven. Zo is de traditionele manier om je liefde voor de goden te tonen door ze te eren, door offers aan te bieden, offers in de zin van ‘iets moois dat je hebt’ aanbieden, en dat kan iets creatiefs zijn, het kan werk zijn, zelfs een park schoonmaken kan een offer aan de goden zijn. En de traditionele manier om met de goden te communiceren, om de goden te ‘verstaan’, om raad en inzicht en advies te ontvangen, is om een divinatiesysteem te gebruiken, zoals de runen of de tarot. En voor de natuurprocessen om je heen kies je een sleutelwoord van iets dat nu op dit moment gebeurt. ‘Oogst’ ligt voor de hand, vanaf Lammas tot Samhain wordt er van alle geoogst, dus oogst is altijd goed ☺ Wat je ook kiest, de vormgeving is essentieel, want een ritueel is per definitie iets dat op het fysieke vlak plaatsvindt, en dat dus een ‘vorm’ moet hebben, gebruik maakt van symboliek enzovoort, hoe simpel je het ook houdt.

Vanaf het moment dat je gaat nadenken over het maken van een ritueel of een opzet, kun je al proberen om open te staan voor spirituele input, voor ideeën en ingevingen vanuit de hogere wereld. Als ik op die manier een ritueel op basis van bovenstaande gegevens samenstel, dan zou dat er als volgt uit zien.

Ik begin met het thema ‘oogst’, dat wordt mijn centrale thema, de kapstok zeg maar. En als centraal symbool in dit thema neem ik een appel. De appel speelt een belangrijke rol in onze westerse mythologie, er zit een verband met Avalon, met de onderwereld en Samhain, en met het pentagram. Die appel wordt horizontaal doorgesneden zodat de vijfster van het klokhuis zichtbaar wordt. Het getal 5 is verbonden met de vijf elementen, en omdat het rituele thema ‘oogst’ is ga ik ook de oogst op het gebied van deze elementen nader uitwerken.

De vijf elementen zijn natuurlijk het aardse element, zaken als geld, een huis, een baan, het water-element, gevoelens, liefdesrelaties, verdriet, het lucht-element, zaken als communicatie, studie, kennis, het vuur-element, passie, hartstocht, levenskracht en gezondheid, en het spirituele element, zaken die met je spirituele ontwikkeling, groei en inzicht te maken hebben.

Als je extrovert bent en veel bezig met dingen maken, en creatief, dan zou je iets dat je hebt gemaakt, of waar je nog mee bezig bent, aan de goden kunnen opdragen. Als een offer, of als iets waar je de zegen van de goden voor wilt vragen. Als het afgelopen jaar, waar je nu (oogst!) de vruchten van plukt, in het teken stond van een liefdesrelatie die nu in de beginfase zit, zou je dus de zegen van de goden daarvoor kunnen vragen, en je daarbij realiseren dat het om het water-aspect gaat.

Als je meer introvert bent en meer behoefte hebt om voor jezelf dingen op een rijtje te zetten, of aan de goden te vragen wat er in hun ogen nou belangrijk was het afgelopen jaar, kun je divinatie gebruiken. Je kunt bijvoorbeeld een tarotkaart trekken. De kleur geeft het gebied aan – een kelken-kaart gaat dus over het watergebied, en de kaart zelf geeft aan om welke ervaring het ging of welke persoon voor jou belangrijk was, of welke rol je zelf vervulde die belangrijk was.

Ik pak opnieuw een paar ideeën bij elkaar om daar een eenvoudig ritueel van te maken. Het thema is dus ‘oogst’, en mijn eigen voorkeur is om iets symbolisch met de goden te delen – dat wordt de appel – en om na te denken over het afgelopen jaar, en ik ga dat doen door de goden te vragen om 5 dingen uit te kiezen die belangrijk waren, één voor elk element.

Ik begin met het laatste, ik verdeel de tarot in vijf stapeltjes, leg elke kleur gesloten bijeen bij de juiste windstreek, en de grote arcana apart in het midden of op het altaar. Als eerste kies ik uit de zwaarden in het oosten willekeurig één kaart, met de vraag aan de goden om mij iets te laten zien dat op luchtgebied, intellectueel, studie etc. van belang was het afgelopen jaar. Wat is mijn ‘oogst’ op het intellectuele gebied? Die kaart leg ik in het oosten. Het is niet echt belangrijk dat je de ‘objectieve’ betekenis van de kaarten kent, het gaat erom welke gebeurtenis uit het afgelopen jaar naar voren komt als jij de kaart ziet, díe gebeurtenis is de kern. Of díe persoon – de hofkaarten mag je uiteraard als mensen zien die belangrijk zijn geweest dit jaar, of als rollen die je zelf hebt vervuld. Ik neem een paar minuten om hierover na te denken. Dan is het zuiden aan de beurt, de staven, vuur, passie, hartstocht maar ook levenskracht en gezondheid. Ook hier de vraag wat de goden belangrijk vonden het afgelopen jaar. In het westen kies je een kaart uit de bokalen, in het noorden uit de pentakels, en tot slot in het centrum een van de grote arcana, en die leg je in het midden, direct voor je.

Als je hierboven het ritueel alvast hebt gevisualiseerd heb je jezelf dus zien zitten in het midden van een cirkel, met vier kaarsen op de vier windstreken, stapeltjes kaarten en één omgedraaide kaart bij elke windstreek, je hebt een paar minuten gemediteerd bij elke windstreek, en kijkt nu weer naar het noorden / het altaar terwijl je met de laatste, vijfde, kaart bezig bent die in het centrum ligt.

Een variatie die mogelijk is, is dat je éérst alle vijf kaarten omdraait, en dan pas per kaart mediteert. Soms is overzicht handig, soms leidt het af. Wat in elk geval zinvol is, is dat je aan het eind de andere vier kaarten nogmaals beziet in het licht van je spirituele ontwikkeling die in de vijfde kaart wordt aangeduid.

Hierna komt de appel aan de beurt. Het kan zijn dat je een mooie tekst hebt, of dat je liever recht uit het hart spontaan iets wilt zeggen, maar de strekking is dat je de appel met de goden wilt delen en daarmee wilt bedanken voor de oogst van het jaar, zoals die nu, in de vorm van vijf kaarten, om je heen ligt. Je snijdt de appel horizontaal door. Vijf kaarten, zoals de vijfster die in de appel verborgen zit. Je legt de beste helft op het altaar en eet de andere helft zelf op. De helft op je altaar die kun je na afloop van het ritueel ergens in de natuur neerleggen.

En daarmee hebben we de hoofdlijnen van het ritueel opgezet. Maar wat veel belangrijker is, je hebt nu zelf in de gaten wat de kern is, en wat er franje is. Natuurlijk is een mooi altaar leuk, en wierook en muziek, maar als je dat vergeet of niet hebt, no problem, want het is niet essentieel. Wat essentieel is, is een pak tarotkaarten en één appel en een mes, en dat is alles. De rest is inderdaad franje, zelfs de kaarsen zijn franje. Natuurlijk, als je het kunt, en het voelt vertrouwd, dan kun je een cirkel trekken. En als je het prettig vindt, kun je wierook branden, en muziek opzetten. Gebruik wel instrumentale muziek zonder teksten – zeker als je zit te mediteren kan muziek je erg beïnvloeden. En natuurlijk kun je een altaar opzetten, en cakes en wijn, en zelfs maankoekjes bakken. En je kunt skyclad werken of in gewaad. En je kunt een speciale dag uitzoeken, volle maan, een jaarfeest of zo. En het zal allemaal bijdragen aan de sfeer. Maar het is niet de essentie. De essentie is heel eenvoudig, eenvoudig genoeg om in een park of bos gedaan te worden, want een voorbijganger ziet niks meer dan iemand die in het gras zit te mediteren en tarotkaarten om zich heen legt. Eenvoudig genoeg om ‘ergens’ tussen Lammas en Samhain gedaan te worden, op een willekeurige dag of avond. Eenvoudig genoeg om op je slaapkamer op bed te doen, als je zoals velen geen aparte plek hiervoor in huis hebt.

Als je het geheel overziet, valt wellicht op dat de appel het centrale thema is, als symbool van de oogst. Via de appel kwamen we op het getal 5, de vijf elementen, en de ‘oogst’ van dit jaar op elk van deze vijf elementaire gebieden, en het gebruik van de tarot omdat de tarot ook deze vijf kleuren kent. Als je nu een ander symbool had gekozen voor een oogst, een korenschoof, of een dier, of zelfs een andere vrucht, een tros druiven bijvoorbeeld, was je dus ergens anders uitgekomen met de verdere vormgeving van het ritueel. Dat betekent dat je de appel dus niet zomaar in dit ritueel kunt vervangen door wat anders zonder dat het ritueel zelf aan coherentie gaat verliezen. Dat is een belangrijke inzichtelijke les in rituelen ☺ Anderzijds laat het ook zien dat je heel veel verschillende kanten op kunt.

Wat ik hiermee heb willen laten zien is dat het niet zo moeilijk hoeft te zijn om een zinvol ritueel te maken, mits je dicht bij jezelf blijft, dicht bij wat voor jou belangrijk is, dicht bij de steekwoorden of sleutelwoorden die je aanspreken. Hiermee kun je een schat aan rituele ervaring opdoen waardoor je ook gepubliceerde rituelen snel zult leren doorzien en de kern of essentie eruit zult kunnen halen. En laat je niet in de maling nemen door de eenvoud – ingewikkelde rituelen zijn ingewikkelder, niet noodzakelijk beter ☺

Ik faal dus als een malle dat ik daar effe geen zin in heb. Misschien speelt ook mee dat dat felbegeerde donker zich net zo makkelijk manifesteert als oorlog. Zal wel ergens heel goed voor zijn en het gaat erom dat beide partijen liever gelijk dan geluk hebben, dat ze de vijand in zichzelf niet kunnen omarmen en over hun schaduwzijde heen kunnen stappen, en die mensen hebben echt nog iets uit te zoeken met elkaar, maar ik blijf me er ongemakkelijk bij voelen.

Ik faal dus als een malle dat ik daar effe geen zin in heb. Misschien speelt ook mee dat dat felbegeerde donker zich net zo makkelijk manifesteert als oorlog. Zal wel ergens heel goed voor zijn en het gaat erom dat beide partijen liever gelijk dan geluk hebben, dat ze de vijand in zichzelf niet kunnen omarmen en over hun schaduwzijde heen kunnen stappen, en die mensen hebben echt nog iets uit te zoeken met elkaar, maar ik blijf me er ongemakkelijk bij voelen.