Abstract

The Triple Moon Goddess of contemporary Pagan and New Age thought is generally assumed to be an invention ex nihilo of the 20th century, with no precursor in classical antiquity, created by the poetic imagination of Robert Graves (1895-1985), with possible inspiration from the classicist and anthropologist Jane Ellen Harrison (1850-1928). However this hypothesis is incorrect. The Triple Goddess was presented in the 20th century before Graves. In addition, this paper is the first to reveal some astrological and esoteric as well as scholarly writings of the 19th century which presented and discussed a triple moon goddess from the ancient world whose identity would have been familiar to most educated men (and a few women) of the time.

Present-day Wicca and Goddess religion take as one of their central deities a threefold Moon goddess who is allegedly of great antiquity. In their influential book The Witches’ Way (1984), Janet and Stewart Farrar state ‘The concept of the Triple Goddess is as old as time; it crops up again and again in widely differing mythologies, and its most striking visual symbol is the Moon in her waxing, full and waning phases’.[i]

The American witch Starhawk in her seminal book The Spiral Dance writes: ‘The Moon Goddess has three aspects: As She waxes, She is the Maiden; full, She is the Mother; as She wanes, She is the Crone’.2 Outside Wicca, Jungian analyst Nor Hall describes ‘the labyrinthine realm of the goddess, where the reigning trinity was feminine’, and claims: These [lunar] phases variously became associated with three weird sisters, three fates, or three goddesses who, when seen together, represented the life span of women from beginning to end.3 The founder of Wicca, Gerald B. Gardner, gives these three phases or aspects names: ‘She is often represented in ancient art as three figures in one, Artemis, Selene and Hecate. Artemis is the waxing moon, Selene the full moon, and Hecate the dark moon.4

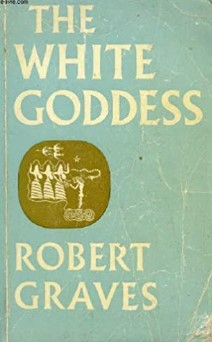

The Triple Moon Goddess is thus claimed to be ancient and (by some authors) universal. Recent commentators, however, for example Michael York and Miranda Seymour, have attributed this goddess’s development specifically to the poetic imagination of Robert Graves (1895-1985), whose ‘historical grammar of poetic myth’ The White Goddess develops the Triple Goddess’s imagery in detail. Ronald Hutton adds that before Graves the poet and occultist Aleister Crowley had also described a triple moon goddess, and concurs with Miranda Seymour that Graves at least may have drawn on the work of the Cambridge academic Jane Ellen Harrison at the turn of the twentieth century.5 Since then we have learned more. The Triple Moon has a much more ancient provenance. In 2000 the present author published a lecture which identified descriptions of a triple Moon in passages by commentators from the ancient world, identified Jane Harrison’s explicit use of these in works not considered by the earlier commentators, and highlighted the role of Hecate, a triple goddess who was specifically linked with the triple moon in this context, as well as with both the murkier side of witchcraft and the exalted heights of mysticism. Parts of this were summarised by Ronald Hutton, together with his own findings, in his collection Witches, Druids and King Arthur, and in 2004 I published a further article investigating the astro-cosmological background to the development of the triple Moon deity in classical and late antiquity.6 This is a beginning, but the question of the importance or otherwise of the Triple Moon Goddess in the public, as opposed to the philosophical, religion of antiquity remains open, and in addition there has been no further investigation of earlier discussions of her in the modern period. Investigating the latter question sheds some light on the former.

Ancient scholiasts and the Triple Moon

In The White Goddess and other works, Graves claims that all goddesses are patterned on the White Goddess archetype. He speaks of her (named after Leukothea, a sea goddess worshipped widely in the Greek maritime colonies) as if she were all goddesses and he identifies her with the moon, saying ‘the New Moon is the white goddess of birth and growth; the Full Moon, the red goddess of love and battle; the Old Moon, the black goddess of death and divination’.6a The harsh, destructive side of the Moon’s symbolism is regularly present in Graves’ writings and is traced by him to English vernacular tradition. Two of his early poems, I Hate the Moon (1915) and The Cruel Moon (1917), attribute to his nurse the belief that ‘the look of the Moon drives people mad’, and references to ‘the horrible strong stare’ of that celestial body recur throughout his poems. Nevertheless, as we shall see, the symbolism of the waning Moon as a cruel goddess was current long before Graves or his nurse. The White Goddess reads as an inspired work interpreting mythological themes both projectively into their use for the practising poet and retrospectively into speculations about the nature of prehistoric religion. Although Graves’ assumptions about prehistoric matriarchy and sacrificial religion were conventional enough at the time, 7 his specific illustrations, for example, the notorious ‘tree alphabet’, and his interpretations of the underlying meaning of historically documented rituals, such as the coronation of the medieval Irish king who bathed in mare’s broth,7a were not. Yet although The White Goddess is a work of interpretation rather than a historical textbook, it still invites historical questions about the extent to which the Triple Moon Goddess figured in the common imagery and interpretation of antiquity. How similar was Graves’ presiding deity to any goddess known from the ancient world?

Graves describes the White Goddess most fully in chapter 22, ‘The Triple Muse’. Here, he cites a precedent from the Renaissance, a poem by the Tudor poet John Skelton, a pioneer of the new Classical learning which was infiltrating the universities at that time, whom Erasmus called ‘the first scholar in the land’, that is, in England.8 This poem, The Garland of Laurell, written in 1523, conjures a spirit:

by these names three:

Diana in the woodes green,

Luna that so pale doth sheen,

Proserpina in Hell.

Graves adds that these three names refer to but a single goddess. He continues:

As Goddess of the Underworld [Persephone] she was concerned with Birth, Procreation and Death. As Goddess of the Earth [Diana] she was concerned with the three seasons of Spring, Summer, and Winter: she animated trees and plants and ruled all living creatures. As Goddess of the Sky she was the Moon, in her three phases of New Moon, Full Moon, and Waning Moon … As the New Moon or Spring she was girl; as the Full Moon or Summer she was woman; as the Old Moon or Winter she was hag.8a

Graves’ equation of this goddess with the three ages of woman is, he says, derived from the ‘Triple Goddess, as worshipped for example at Stymphalus’, that is, Hera, who had three temples there where she was worshipped as a girl, as a married woman and as a widow; Graves cites Pausanias, the second century BCE author of an extant ‘Description of Greece’.8b

As a competent classicist, a product of the normal education of a young gentleman in the early twentieth century, Graves’ poetic talent was trained in the composition of Latin and (to a lesser extent) Greek verse. His version of the Argonautica, his translation of Apuleius’ Golden Ass, his accounts of the Greek and Hebrew myths9 are exhaustively researched, albeit embellished, and later, in The Greek Myths, published seven years after The White Goddess, he meticulously lists the ancient sources of his information and interpretations. He is not likely to have invented these interpretations out of thin air. The identity of Luna, Diana and Proserpina had in fact been given long before Skelton by one of Graves’ ancient sources, the fifth-century commentator Servius. Glossing Vergil’s Aeneid IV 511, which mentions ‘triple Hecate, the three faces of the virgin Diana’. Servius comments: ‘When [Diana] is above the earth she is believed to be Luna; when on earth, Diana; when below the earth, Proserpina.’ Servius’ commentaries were available in Skelton’s day, and a paraphrase of this passage even appears as a note to modern school editions of the Aeneid, which implies that it has been a standard interpretation for some time.10 Graves mentions Servius and other commentators (as well as the Greek magical papyri) in his footnotes to The Greek Myths (for example chapter 31, ‘The Gods of the Underworld’), in which he also observes that Hesiod’s account of Hecate (in the Theogony 411-52) shows her to have been ‘the original Triple-Goddess, supreme in Heaven, on Earth and in Tartarus’.

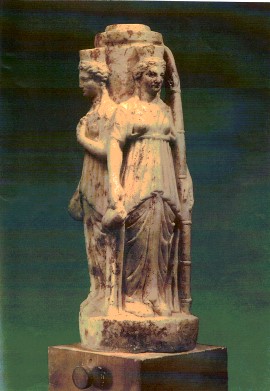

(From N. Papamatzis, Ancient Corinth, Ekdotike Hellados, Athens, 1978)

Graves’ further comments on these three levels of lunar rulership (heaven, earth and underworld) amalgamate several ancient sources. Those on the first and last levels are straightforward. Continuing his explanation of the Triple Moon in the Aeneid IV 511, Servius continues, ‘to the one goddess people assign the powers of birth, active life and death’. He does not identify that goddess specifically with the underworld goddess Proserpina, as Graves does, but with the Moon. We should note however that birth, active life and death are the powers of the three Fates, who will appear in what follows. Concerning the celestial level, a goddess of the sky identical with the three phases of the Moon is described in many philosophical commentaries, e.g. Cornutus on Theocritus’ Idylls 2.12 (a different section of which is quoted by Graves in The Greek Myths 31), but not for the phases given by Graves. The ancient scholiasts’ phases are explained as the crescent, half and full moon, not the waxing, full and waning phases. However every classically-trained schoolboy would have known that waxing, full and waning lunar phases were recognised in the ancient Greek calendar. This was measured by the lunar month, divided into three ten-day phases beginning at the new moon. These phases were actually called ‘waxing’, ‘middle’ and ‘waning’ (as in Hesiod’s Works and Days 819-21), which gives all three instances of the fourth day of each ten-day period (called ‘decanate’ in the remainder of the present paper). At a fundamental level then for the ancient Greeks the moon was the month and was divided into three equal phases.

J.E. Harrison: the Moon as mother of the Seasons

Graves’ version of the waxing full and waning moon draws not only on these sources, who are listed in the footnotes to The Greek Myths, but also, it seems, on an early twentieth-century commentator, as we see when we investigate his middle image, that of the goddess Diana as spring, summer and winter, the three seasons of the ancient Greek year. A link between the decanates of the triple month and the three seasons was offered by Jane Ellen Harrison, who is indeed proposed by Seymour and Hutton as a major influence on Graves. Her theory is found not in Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, where it is sought by these researchers, but in her even more influential book Themis. Here Harrison claims explicitly that triple goddesses such as the Fates, Charities and Hours (i.e. Seasons) are derived from the triple Moon and she links them with the triple Hekate as the latter’s attendants. In two rather dense passages she states (the interpolations in square brackets are mine):

The triple Charites who dance round the column [of Hekate in the museum at Prague] are triple because of the three phases of the Moon. . . . The Horae or seasons of the Moon, her Moirae, are preceded by the earlier Horae, the Seasons of Earth’s fertility: at first two, spring for blossoming, autumn for fruit, then under the influence of a moon-calendar three.11

The three Horae [Seasons] are the three phases of the Moon, the Moon waxing, full and waning … the Moon is the true mother of the triple Horae, who are themselves Moirae [apportionments, Fates], and the Moirae, as Orpheus tells us, are but the three moirae or divisions (mere) of the Moon herself, the three divisions of the old Year [already explained by Harrison as the lunar month: Servius: Aeneid V 284]. And these three Moirae or Horae are also Charites.12

In The Greek Myths Graves offers what is effectively a paraphrase of the second passage, with an additional gloss on the three ages of woman:

The Moerae, or Three Fates, are the Triple Moon-goddess … Moera means ‘a share’ or ‘a phase’, and the moon has three phases and three persons: the new, the Maiden-goddess of the spring, the first period of the year; the full moon, the Nymph-goddess of the summer, the second period; and the old moon, the Crone-goddess of autumn, the last period.12a

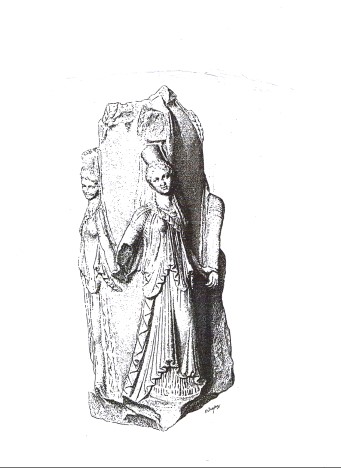

The Three Graces dancing round a (headless) statue of Artemis/Hekate Epipyrgidia

Since Graves tells us (in the introduction to The Greek Myths) that he had read Harrison’s Prolegomena at least, these two passages suggest that he had also read Themis and borrowed directly from its author, particularly in his linking of the moon’s phases with the seasons. Their association with the three stages of a woman’s life is alluded to not only in The White Goddess (see above) but also in Graves’ introduction to The Greek Myths,13 where he introduces the three phases of the moon as, once more, the three ages of woman and the three seasons of the year, also as the three levels of air, earth and sea with their three presiding goddesses, as in Servius above, and ends with a reference to their attribution to a single goddess in the three shrines of Hera at Stymphalus. If Graves was not actually drawing on this passage in Harrison’s work, he appears to have read the same ancient authors and drawn exactly the same conclusions.

Jane Harrison’s own assertion is referred by her to the Orphic commentators of antiquity. Texts attributed to Orpheus, the legendary poet and musician who may or may not have lived in the unchronicled age before the Trojan War, were claimed as inspiration by religious and philosophical sects from the sixth century BCE onwards, with a major burst of composition during the first two centuries of our era. This latter period was itself a time of syncretism and the systematisation of previously unrelated cults, but the process had been going on among scholars at least since Ptolemy I of Egypt founded the great library at Alexandria around 300 BCE. It is from this earlier period that Harrison’s footnoted reference to Orpheus comes. She refers the reader to Epigenes, a Greek grammarian who was active in the third century BCE.14 Epigenes is quoted by the 2nd-century Christian martyr Clement of Alexandria as reporting that Orpheus ‘said the Fates are … divisions of Selene: the thirtieth and the fifteenth and the first [literally “the new moon”]’.14a In other words, the days (or longitudinal degrees, another meaning of moira) of the New Moon, Full Moon and Dark Moon, the first, middle and last day of each of the three decanates of the 30-day lunar month described above, are equated to the Spinner, Measurer and Cutter of the thread of life, the three Fates. (The ancient calendrical and astrological theories which formed the background to Epigenes’ interpretation are discussed in my 2004 article; see footnote 6.)

Here then is our threefold Moon of the waxing, full and waning phases, and here is her link to triads of goddesses such as the Fates and the Graces. Harrison’s second footnote to the passage in Themis refers us back to an earlier book, Mythology and Monuments of Ancient Athens (1890), in which she discusses the joint worship of the three Graces and ‘Hekate the Moon’, although, as she tells us in Themis, ‘I did not then see that the triple form had any relation to the Moon’.15 In this earlier study she links the Graces not with the Fates, the three stages of human life, but with the Seasons, which in Greece were also triple. Later, in Themis, two pages after the passage quoted above, Harrison emphasises the likely importance and antiquity of the worship of the Moon ‘in her triple phases’ from Cretan times on, and later asserts that ‘Moon-elements are found in nearly all goddesses and many heroines’.16

Jane Harrison’s writings, then, are a clear prototype of some passages in Graves’ work. Moreover, both authors refer to ancient texts which explicitly state the existence of a Triple Moon Goddess who is also identified with three other goddesses of independent origin. It was not only professional academics who drew attention to the composite lunar deity, however. The esoteric current of the late nineteenth century also knew of the Triple Moon.

Astrologers and mystics: the esoteric tradition

A similar figure to the Graves’ Triple Goddess had been described fifteen years earlier by the magician, poet and novelist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) in his own novel Moonchild:

For she [i.e. the Moon] is Artemis or Diana, sister of the sun, a shining Virgin Goddess; then Isis-initiatrix, who brings to man all light and purity, and is the link of his animal soul with his eternal self; and she is Persephone or Proserpine, a soul of double nature, living half upon the earth and half in Hades … and thirdly she is Hecate, a thing altogether of Hell, barren, hideous and malicious, the queen of death and evil witchcraft.17

These are three of the usual goddesses, plus a fourth, Isis, herself most famously described as the Moon in the second-century novel by Apuleius, the Metamorphoses, or The Golden Ass. A note to the first edition of Moonchild states that the novel was written in 1917, when the author was in America, and indeed a very similar passage appears in the unfinished Treatise on Astrology (Liber 536), which Crowley wrote also, in collaboration with the American astrologer Evangeline Adams, in 1917-18 but which was not published until 1974, long after his death, and so is unlikely to have been available to Graves and Gardner. (According to Crowley’s diaries, Gardner met with Crowley on three separate days in May 1947 and discussed not the Moon Goddess but the establishment of a branch of the latter’s magical order, the OTO, in Britain. Gardner met Graves only in January 1961, after the publication of The White Goddess and of Gardner’s books and magical rituals, when he and the Sufi writer Idries Shah came to visit Graves in Majorca.18) Crowley’s passage runs:

One of the favourite epithets of the Moon-Goddess among the Romans was Trivia, she of the three ways, because she had three forms. She is woman, both as mother and as child … There is however a certain sinister aspect of the life of a woman to understand. … Among superstitious peoples, [the embittered post-menopausal woman] would . . . obviously acquire the reputation of being a witch. The waning moon was, therefore, taken as the symbol of every kind of devilry. She is Hecate, the Queen of the Stryges. A good modern picture of this idea is given in “Macbeth”.19

Crowley too was a poet of some ability and great learning, like Graves thoroughly competent in the ancient classics but equally a creative writer rather than a scholarly analyst. He read Hebrew and Persian as well as Latin and Greek,20 and was familiar with the literature of these languages, as a glance at his opus will demonstrate. His early poem Orpheus: a Lyrical Legend (1905) displays a formidable grasp of versification; he wrote an account of the voyage of the Argonauts (as did Graves) as also of the legends of Osiris, of Ahab and of Jezebel; and, looking forward to the creation of a new Irish republic, he named one of his poems after Horace’s Carmen Saeculare, the festival ode with which the emperor Augustus inaugurated the Roman ‘New Republic’ in 17 BCE. Quotations and adaptations from the works of ancient authors pepper his texts.21 With this background, Crowley’s description of his lunar goddess, like that of Graves, is likely to be drawing directly on ancient originals.

Crowley’s identification of the moon with womanhood is however partly a modern phenomenon. As Hutton has demonstrated in detail,22 the symbolism of the Moon Goddess became increasingly prominent in European art and literature from the Renaissance onwards, gaining strength as a counter-cultural image after the Enlightenment. In English literature indeed she ousted the native Sun Goddess. Milton’s lines from the mid-seventeenth century:

For yet the Sun

Was not; shee in a cloudie Tabernacle

Sojourn’d the while,22a

could not have been written fifty years later. During the Enlightenment, the Moon Goddess began to be seen as the archetype of Woman.

Crowley’s comments in Moonchild and the Treatise on Astrology, to the effect that the Moon is Woman, are however also consonant with an astrological commonplace, going back to the earliest astrological texts from the ancient world. The Roman poet Manilius in his Astronomica (c. 9 BCE) describes the third and ninth houses of the horoscope as complementary realms, called “Goddess” and “God”, the abodes of the Moon and the Sun respectively. The Moon, the poet tells us, also “mirrors what is fated in the fading edges of her face”, recalling Epigenes’ identification of the three Fates with the Moon’s successive phases.22b Later the astrologer Ptolemy, writing in the second century CE, tells us:

since there are two primary kinds of natures, male and female, and of the forces already mentioned that of the moist is especially feminine … the moon and Venus are feminine, because they share more largely in the moist.22c

In medieval and early modern astrology the Moon primarily signified women, and this has continued into modern psychological astrology.23 Crowley’s description of the Moon as a threefold being, by contrast, is not part of mainstream astrology, despite Manilius’ gentle hint. Nor is Crowley’s emphasis on the Moon’s baleful influence, reiterated in his and Adams’ section on Neptune and the Moon:

Venus has a certain ease and jollity: the Moon is cold, dim, mother of illusions … Alone she is but the planet of witches; strange beasts prowl in the darkness; poisoners gather their deadly herbs beneath her as she wanes … in combination [Neptune and Luna] bring the maximum deviation from balance, and all unbalanced force is evil.

His American co-author Evangeline Adams, in her own later book Astrology, Your Place Among the Stars, omits both Crowley’s threefold imagery and his negative attitude. She names the Moon ‘Selene, or Diana, or Luna’, and describes her as ‘complete woman, in all phases, untouched by male caresses’. But these three names are used practically as synonyms, with no reference to Proserpina or Hecate, and Adams goes on only to describe two phases, the waxing phase (‘the child, innocent and receptive … also huntress like her brother Apollo’), and the full moon (‘glorious … She is now Sophia, the Virgin Wisdom of the Father’). Madness and infatuation are ascribed by Adams to the waxing moon, but only in response to an impious approach by the human seeker, and the prevailing tone of her whole description is rapturous and positive.24 So is Crowley’s jaundiced attitude and emphasis on a threefold astrological Moon merely the product of his own background and imagination?

Of his background, certainly, but not necessarily in the psychoanalytic sense. Crowley trained as an occultist in the Golden Dawn, which he joined in November 1898. The training manuals of the Golden Dawn at the time included a brief coverage of astrology,25 and published versions include, in the Third Knowledge Lecture, a reference to that luminary’s three phases ( ‘In its increase [the Moon] embraces the side of Mercy; in its decrease the side of Severity, and at the full, it reflects the Sun of Tiphereth’)26 and a possible allusion to triplicity in the assignation of the triple number 369 to ‘Chasmodai, the Spirit of the Moon’. 27 More important however is the fact that the Golden Dawn, founded in 1888, came into being some thirteen years after, and partly in response to, the Theosophical movement of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-89). One of the founders of the Golden Dawn had allegedly turned down Mme Blavatsky’s offer to co-found the Theosophical Society with her, and in their early years the two organisations had members in common.28 Israel Regardie, the great exponent of Golden Dawn teachings from the 1930s on, as well as sometime secretary to Crowley, regularly refers the reader to Blavatsky’s writings, and Crowley himself published her mystical work The Voice of the Silence in his own periodical The Equinox (III, 1). Blavatsky’s work permeated the occult circles of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; her synthesis of Oriental and Western mystical doctrines, published in Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), as well as the work of the Theosophical Society, laid the foundation for twentieth-century New Age spirituality and stimulated existing magical lodges to reformulate their teachings in response to hers.

Here is where we find unambiguous reference to the malevolent Triple Moon. For Blavatsky, writing about esoteric systems generally rather than the specifically astrological, the Moon was:

“the cold residual quantity, the shadow dragged after the new body [the Earth], into which her living powers and ‘principles’ are transfused. for she is a dead, yet a living body. Constantly vampirised by her child, she revenges herself on it by soaking it through and through with the nefarious, invisible and poisoned influence which emanates from the occult side of her nature … The particles of her decaying corpse are full of active and destructive life, although the body which they had formed is soulless and lifeless. Therefore its emanations are at the same time beneficent and maleficent – this circumstance finding its parallel on earth in the fact that the grass and plants are nowhere more juicy and thriving than on the graves; while at the same time it is the graveyard or corpse-emanations which kill. And like all ghouls or vampires, the moon is the friend of the sorcerers and the foe of the unwary.”29

This jaundiced view is presented as a scientific description of the physical nature of the Moon. The satellite’s ‘metaphysical and psychic nature’ is kept as ‘an occult secret’ (ibid.), but it may perhaps be guessed at from Blavatsky’s description of lunar symbolism:

For the ‘Fathers’ – such as Origen or Clemens Alexandrinus [elsewhere described as initiates of the pagan temples – PHJ] – the Moon was Jehovah’s living symbol: the giver of Life and the giver of Death, the disposer of our being … For, if Artemis was Luna in heaven and, with the Greeks, Diana on earth, who presided over child-birth and life: with the Egyptians, she was Hekat (Hecate) in Hell, the goddess of death, who ruled over magic and enchantments. More than this: as the personified moon, whose phenomena are triadic, Diana-Hecate-Luna is the three in one. For she is Diva triformis, tergemina, triceps – three heads on one neck [footnote: “The goddess Trimorphos in the statuary of Alkmenes”], like Brahma-Vishnu-Siva. Hence she is the prototype of our Trinity, which has not always been entirely male.30

Here then is the threefold Moon of antiquity, presented in a standard text of the nineteenth-century occult revival, earlier than Harrison’s writings, with references to commentators both ancient and modern. In this passage Blavatsky refers to the poet, journalist and amateur Egyptologist Gerald Massey (1828-1907); elsewhere to the ancient authors Damaskios, Porphyry and Hesiod, and to the eighteenth-century Cambridge Platonist Thomas Taylor.31 As the passage above demonstrates, Blavatsky’s work is a polemic rather than a critical study, yet it is a polemic based on wide critical reading or discussion. Who were her informants? It turns out that Jane Harrison was far from being an isolated thinker. When we turn to academic theories contemporary with Blavatsky and the Golden Dawn, we find the Threefold Moon Goddess traced – and debated – in detail.

A nineteenth-century link? Diana Nemorensis

One ancient example of a triple Moon goddess achieved great prominence in the English-speaking world at the turn of the twentieth century. The monumentally influential work of Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough, expanding through three editions between 1890 and 1912, made a Roman triple Moon goddess and her priest-king into the paradigm image of archaic, prehistoric religion for the twentieth century. All three editions of Frazer’s work open with the same vivid description of the grove of Diana Nemorensis, Diana of the Woodland Glade, whose shrine lay in the Alban Hills within sight of Rome. Although Frazer does not mention the fact, every classical scholar and public schoolboy would have known that this particular Diana was known by classical times as a goddess of the Moon who was three in one. As Crowley observes, she was surnamed Trivia: ‘She of the Three Ways’.

Poetic references to the threefold Diana from the ancient world which would have been familiar to all educated people (thus Graves and Crowley) in the early twentieth century include the first century poet Martial, congratulating the emperor Domitian on his property: ‘From here (the Alban hills) you can see Trivia’,31a and mentioning the ‘kingdom of Trivia of the grove’.31b Horace describes her as ‘thrice invoked … a triple goddess’,31c and Virgil in the Aeneid VII 516 calls Lake Nemi, known as the ‘mirror of Diana’ in her grove, ‘Trivia’s lake’.31d The epithet Trivia, a translation of the Greek Trioditis, ‘She of the Three Ways’, is properly used not of Diana but of Hekate, whom Graves mentioned as the original Triple Goddess. As we have already seen, Hekate, an Anatolian goddess known from earliest times in Greece, was associated there with three roads (perhaps originally the three celestial ‘Ways’ of heaven, earth and underworld), as well as with death, harmful magic and the underworld. By the first century BCE, the ‘Golden Age’ of Latin literature with which nineteenth-century schoolboys were generally familiar, the name ‘Trivia’ retained sinister overtones but was regularly used of Diana and of the Moon generally, not simply of Hekate or even of Diana Nemorensis. Catullus, in a poem to Diana, first apostrophises her in her familiar form as maiden, daughter of Jove and Latona, mistress of mountains, woods, chasms and other wild places, then adds: ‘You are called Juno Lucina by women suffering in childbirth, you are mighty Trivia and by its familiar light are called the Moon; you, Goddess, measur[e] the monthly course of the year.’31e Likewise equating Diana with Trivia and the Moon, the learned Varro, Catullus’ contemporary, speculates how ‘Titan-born Trivia is Diana, and she is called Trivia … perhaps because she is said to be the moon, which moves along three paths in heaven: in altitude, latitude and longitude.’31f Here then is Diana, in literature with which all well-read Victorian gentlemen would be familiar, as a triple Moon goddess. She is seen the as goddess of three ways and equated with the moon, but she is not specifically identified with the waxing, full and waning Moon.

The Roman poets knew, although Graves and Crowley would not have known, that Diana at her temple in the grove was actually portrayed as triple. At the very time that Graves was producing his final revision of The White Goddess, archaeologists were in the process of identifying the goddess of Nemi’s image at the site. The temple image, as imagined or recorded on a series of coins minted in 43 BCE at Aricia, had the form of three figures standing side by side, linked together by a crossbar in an archaic design typical of the fifth century BCE. Each figure carried the attribute of a particular goddess: a bow for Diana, a poppy for the moon goddess Luna, ruler of sleep, or perhaps for Hekate, and an indistinct object, possibly a pomegranate, for the underworld goddess Hekate or Proserpina. In the imagination of coiners and possibly in the temple image itself, it thus seems that Diana Nemorensis was indeed portrayed, at least in the first century BCE, as the trinity described by the scholiasts and later by Skelton as Diana/Artemis, Luna/Selene, and Proserpina/Hekate.32 Luna and Hekate/Trivia are identified with Diana in the texts above, and we have already seen Servius’ much later explanation, c. 400 CE, of another contemporary reference, that of Virgil in the Aeneid IV 511 to the vengeful Dido invoking ‘triple Hecate, the three faces of the virgin Diana’.32a

(The Lariscolus coin image is from Alfoldi 1960)

Here then is another available inspiration for Graves’ and Crowley’s Triple Moon Goddess, and interestingly, when Gerald Gardner’s witch religion was challenged in the 1960s by a rival contender, the latter adopted the very title of the priest of Diana at Aricia: Rex Nemorensis. 33 The implication is that he was re-enacting the ritual combat described by Frazer as conferring the priesthood of the grove. To gain this each contender, usually a runaway slave with little to lose, had tear a branch from a sacred tree in the grove and then fight the existing holder, known as the King of the Grove, rex nemorensis, to the death. Yet whatever might later have become the case in Gardner’s witch cult, Diana Nemorensis does not figure as the prototype of Graves’ Triple Moon Goddess. Graves refers to her in The White Goddess33a and briefly mentions her feast-day on the Ides of August (itself described by Statius, another poet of the Golden Age, in his Silvae, referring to the ‘Aricinian grove of Trivia’33b), but does not discuss her triplicity and uses a late source, the fifth-century CE poet Commodianus, to identify her with Nemesis, the Greek goddess of retribution. Chapters 101 and 116 of The Greek Myths give the origin myth of the holy site at Aricia, specifically identifying the bloodthirsty Artemis of Taurus, the supposed prototype of Diana Nemorensis, with Hekate and adding ‘to the Latins she is Trivia’ (with a reference to Servius).33c Thus we have the equation of a particularly savage version of Artemis with the Greek Nemesis and Hekate and with Diana Trivia in her grove at Aricia, but neither of these chapters mentions the three phases of the Moon. Chapter 31, identifying Hekate on Hesiod’s authority as ‘the original Triple Goddess, supreme on heaven, on earth, and in Tartarus’,33d adds that the Greeks had emphasised her destructive qualities at the expense of her beneficent ones and made her into the queen of the (destructive) witches and companion of Proserpina the underworld queen. Graves therefore does not present Diana Nemorensis as the prime image of his triple goddess of the waxing, full and waning Moon, but as a being of savagery who is only incidentally triple.

Frazer too emphasises not the Aricinian goddess’s triplicity but her savagery, suggesting that this is a primeval form of religion. He refers to Virgil’s description, in Aeneid VI 136, of the ‘golden bough’ which the mythical ancestor of the Roman ruling family, Aeneas, was obliged to offer to Proserpina the underworld queen,33e and which Servius says was the same bough that featured in the ritual combat which characterised Diana’s priesthood and which Frazer presents as the opening image of his book. It was this bloody combat, and not the threefold nature of Diana, which drew Frazer’s attention. Frazer intimated that the ‘king’ and his office were an example of ‘primitive’, magical religion which had somehow persisted unchanged into a civilised age.34 The priesthood of Diana Nemorensis was in a sense to be taken as the paradigm of all priesthoods, an early model of pre-civilised humanity, and Diana herself was thus available be seen as the prototypical ancient goddess. Yet Frazer did not even mention Diana Nemorensis’ triple nature. He stresses her role as a goddess not of the Moon but of wild Nature, of healing and midwifery, and as patroness of prisoners and slaves: a powerful counter-cultural image. He dwells on the bloodthirstiness of her priesthood and her apparent origin as a Great Goddess in Asia, presiding over fertility but not marriage, worshipped with orgiastic rites and paired with a subordinate god who in Sparta, for example, was called Karneios, a name which seems to have produced variants in modern Wicca.35 Indeed, later in The Golden Bough Frazer’s model of a many-faceted Great Goddess is not triple but dual, not lunar but chthonic, that of the corn-mother Demeter and her daughter Kore or Persephone.36 All these features resurface in present-day Pagan nature-worship, but with the addition of the goddess’s triple nature as recorded by the Roman poets and presumably thought by them to be archaic, the sanctuary ‘sacred to an ancient rite’ as Ovid has it in his Fasti36a.

The Golden Bough then does not offer a direct clue to the re-emergence of the Triple Moon Goddess, but the wide-ranging impact of Frazer’s central image, the bloodthirsty ritual of Diana of Aricia, may well have reminded Edwardian classicists of that goddess’s triple nature. In any case, Graves does not present his Triple Moon as an established goddess of Roman or even Greek religion, but as a dimly-glimpsed shadow from the Stone Age, whose worship had been distorted (according to the archaeological orthodoxy of the time) by patriarchal invaders attacking late Minoan culture.37 The present investigation does however suggest that that the Moon goddess acquired increased importance during the late Republic and early Empire in Rome. As we have seen, a poem from that period, the Astronomica of Marcus Manilius, hints at soli-lunar duotheism, describing how astrologers allot ninth house activity to ‘the God’, who is the Sun, and the opposite third house to ‘the Goddess’, the Moon, though she is not in this case a triple being (see note 22b). At the inauguration of his ‘New Republic’ at the Secular Games in 17 BCE, the emperor Augustus had inaugurated the worship of Apollo (as Sun god) and Diana (as Moon goddess) as the prime celestial deities, apparently dominating the traditional deities of Rome and of Olympus. In addition it is also from the early Common Era that the first astrological commentaries on the identity of Luna, Diana and Hekate/Proserpina come. These clues require fuller investigation separately, but as far as precursors of Graves are concerned, Franz Cumont, who in 1912 published a series of lectures on astral religion in the ancient world, was of the opinion that by the early third century CE this stellar philosophy, originally the preserve of a few intellectuals, had become the all-pervading theology of the Roman Empire. Graves, according to his own boast, had certainly read much of the literature of later antiquity, if not Cumont’s lectures themselves.38 In the same way, the process by which in fifth-century Athens links were forged between Artemis, the prototype of the triple goddess of Nemi, Selene, Hekate and Persephone, would seem less self-evident than is normally supposed. 39 To develop these topics would however be a diversion from the present subject, the nineteenth-century precursors of Graves.

Scholarly sources: the German encyclopaedists

Jane Harrison’s own sources, credited in her footnotes and acknowledgements, are the academic commentators, particularly the German researchers, of the previous fifty years. The great scholarly compendia of the nineteenth century, dictionaries of classical antiquity which continue to be used as reference works today, debated the issue with some gusto. Here we find many prototypes of the twentieth-century Triple Moon Goddess. Harrison’s own argument that the Charites are triple under the lunar rulership of Artemis-Hekate, which she refers to ‘the mythological acumen of Dr Robert … from whom the whole of this view is taken’, had also appeared in W.E. Roscher’s lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology.40 In these discussions the triple goddess is generally seen as Hekate rather than Luna or Artemis, though not invariably. Thus Roscher’s Lexikon explains the image of the waxing, full and waning Moon as the three faces of Hekate, although Preller-Robert’s Griechische Mythologie dismisses the lunar interpretation of Hekate’s three faces as an invention of the philosophers of late antiquity but still sees Artemis as primarily a Moon goddess rather than, as present-day scholars generally believe, a goddess of the wilds.41 Other commentators such as Pauly and Wissowa and the Oxford classicist L.R. Farnell stood out against the lunar interpretation of both goddesses, seeing Artemis primarily as a deity of agriculture and fertility, attributing her lunar rulership essentially to the poetic imagination of the Roman writers of the Golden Age quoted above, and seeing Hekate as primarily the triple goddess of heaven, earth and underworld, or rather sea, described by Hesiod.42 Two extended articles require special mention. In 1880-1 Eugen Petersen’s three-part article ‘The Triple Hekate’ in the Archäologisch-Epigraphische Mittheilungen aus Oesterreich 43 exhaustively surveys the then-extant triple statues from the ancient world, the Hekataia, catalogues them by salient features and discusses their interpretation by ancient commentators, including Hekate’s association with various triads of goddesses, lunar phases and calendar decanates, three-way junctions and cosmic strata that we have already encountered above. Petersen writes of Hekate and Artemis throughout as Moon goddesses. His discussion of the triads of maidens dancing around some triple Hekataia, the impossibility of deciding whether they are Nymphs, Hours or Charities, and the association of these and the Muses with ecstasy, mania and prophecy,44 anticipates some of Harrison’s and Graves’ themes, as does his attempt to interpret the images on the robe of the Hekate of Hermannstadt in the third of his articles, which Harrison also attempted in Mythology and Monuments.45 Petersen’s line drawings of the Hekataia are reproduced facsimile by Harrison and credited as such by her.46 The other article, also cited by Harrison, is that on ‘Triplicity’ by Dr H. Usener (1902-3), 47 again a systematic overview but this time of triads of deities from a wide range of cultures. Its third section includes an investigation of the alleged development of Hekate from a double to a triple form, supposedly occasioned by the increasing importance of the concept of triplicity and thus the introduction, at an unspecified date, of the triple lunar month, which ‘unavoidably affected the depiction of the Moon Goddess and led to her three-bodied form with its resultant manifestations’.47a Here once more a triple Moon Goddess is taken for granted, is identified primarily with Hekate and is explained with reference to the three decanates of the lunar month, the waxing, full and waning moon, and later47b to the other triplicities given by the poets and their scholiasts.

These examples demonstrate the existence of an extensive discussion in the nineteenth century, long preceding Robert Graves, of the nature of a triple Moon-goddess already familiar from the images, poetry and philosophy of antiquity.

What was its impetus? As mentioned above (p.10), an interest in the Moon Goddess as a romantic symbol of femininity had been growing throughout the modern period in western Christendom. Interest in triple deities may also have been linked with the new Biblical scholarship of the time, placing Hebrew and New Testament religion within the same historical and anthropological spectrum as other religions, with the result that for example Usener could confidently assert, ‘The Christian dogma of the Trinity of God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost was not revealed, but developed and grew under the influence of the same internal pressures whose effects we have seen among the religions of antiquity,’ a conclusion which is now accepted historiography.48 In the preface to the second edition of Themis in 1928, Jane Harrison observed that the present generation of scholars, to her great relief, took almost as ‘matter of historical certainty based on definite facts’ the ‘heresies’ which she had proposed and which had seemed ‘rash’ to her colleagues at the turn of the century. These included ‘that gods and religious ideas generally reflect the social activities of the worshipper’ and ‘that the Great Mother is prior to the masculine divinities’.49 These were the orthodoxies which Robert Graves took for granted.

The Triple Goddess takes definitive form: Briffault, The Mothers

However the first systematic presentation of the Triple Moon Goddess in the twentieth century was not made by Robert Graves but, so it would appear, by Robert Briffault in his three-volume set The Mothers, some 2100 pages of text published in 1927, over twenty years before The White Goddess.50 Here we see all the main features of the New Age Triple Moon Goddess, particularly encapsulated in chapter xix, ‘The Witch and the Priestess’, and chapter xx, ‘The Lord of Women’. The Moon deity, at first a god, later a goddess, is here said to be a feature of primitive matriarchy, part of a religion which ‘in its primitive stages is indistinguishable from magic’,50a a women’s religion which is ‘not speculative, but practical’, owing to the ‘inaptitude of women for abstract speculation’,50b in which it is believed that ‘woman derives her powers as a witch, like her powers of reproduction, from the moon’.50c Chapter xx tells us that Moon deities are ‘commonly triune’, and gives examples from around the world including the Greek goddesses and the commentaries of their interpreters already discussed. It adds that the moon is seen by many cultures as dangerously ambivalent and taboo, a feature that recalls to us Graves’ cruel Goddess; that it is seen as the source of divine inspiration as well as lunacy; that it is the source of magic power; and that it is associated worldwide with such attributes as the hare, the dog and the serpent. Chapters. xxi and xxii argue that the waxing and waning of the moon are the prototype not only of human ideas of immortality and reincarnation but of all mathematical cosmology and calendration ands thus that the moon is the source of the “higher” cosmic, abstract religion. These same features also make the moon the personification of fate and of the threefold goddesses of fate.50d Here Briffault reproduces the Orphic and philosophical passages which we have already seen in Harrison and her German predecessors, interpreting the three Fates as the powers or ‘divisions’ of the Moon and claiming likewise that in origin and functions it is difficult to distinguish the Musae from the Horae from the Charites etc. Every assertion has a footnote, including not only the ancient writers discussed above, but also interpreters and ethnographers from the nineteenth century going far beyond (though of course including) Harrison, Roscher, Petersen and Usener. Later Briffault criticises Farnell’s disputation of the triple nature of the lunar deity:50e in brief, his work is not only a seminal presentation of the Triple Moon Goddess theory but also through its extensive references allows the development of its argument to be traced.

Briffault’s work, with its accumulation of (alleged) examples from around the world, can be placed in the anthropological tradition which immediately followed Frazer, before the professionalisation of the field, aiming at universal generalisations about human society rather than the isolated findings within a narrow field of expertise which both preceded it and have followed it. Like Frazer’s work it is open to criticism because of overgeneralisation and misinterpretation of its sources: vol. II p. 602 for example claims, on the authority of an article published in 1863 about Arabian concepts of fate, that the Arabian goddess Manat was threefold, a moon goddess and the goddess of fate, as well as (following an 1880 book of German folk-tales) that the Teutonic Norns, like the Greek and Roman Fates, were likewise moon-goddesses. Such a wide-ranging approach however has the strength of being able to challenge special pleading based on ignorance of relevant data outside one’s own field – a charge levelled by the new anthropologists at, among others, Christian theologians of the time. Like The Golden Bough, The Mothers also spoke the twentieth-century language of science, which would gain it readers in a scientific age. Whereas Graves’ thesis, albeit a commentary “logically deduced from reputable ancient documents”,51 on the then-orthodox theory of Stone Age matriarchy and the Great Goddess, is a work of poetic interpretation, Briffault’s study is presented non-poetically, anthropologically, and as a series of incontrovertible observations. The lunar deity of The Mothers is described not as an archetypal being, the poet’s muse or the wellspring of femininity, but simply as a naïve personification of the visible moon in its various phases, explained in the evolutionary paradigm of Briffault’s age as a pre-scientific attempt to explain and control the world, to be replaced in the fulness of time by proper scientific theory.

As a literal description Briffault’s account appealed to systematic as well as to inspired thinkers. Its attempt to describe a universally widespread pattern of social ordering attracted the attention of a Jungian theorist, Dr M. Esther Harding. Her book Women’s Mysteries Ancient and Modern, published in 1955,52 generously acknowledges Briffault’s work as ‘invaluable in making the present study’ but does not so much as mention Graves. Harding also draws on nineteenth-century and earlier theorists of the triple Moon, including Goblet d’Alviella, La Migration des Symboles, (1894), Félix Lajard Sur le Culte de Mithra (1847), and apparently a publication from 1774, A New System or Analysis of Ancient Mythology, by Jacob Bryant.53 D’Alviella’s commentary on the coin from Metapontus, bearing a triscele image, which Harding reproduces as ‘Coin of Mesopotamia entitled “Hecate Triformis”’ and explains as the crescent, full and dark moon, is in fact to the effect that this coin is of later date than the solar trisceles he has already identified but that the three aspects of the crescent, half and full moon, explained as the source of the three faces of Hecate Triformis by the commentator Cleomedes [in the second century CE], gradually caused the simple symbolism of the lunar crescent to multiply to a triad shaped in imitation of the pre-existing solar triscele.54 Harding, whose much shorter book of some 250 pages is cited as a reference by Nor Hall in the book quoted at the opening of this article, gives what is effectively an accessible précis of Briffault, including the threefold lunar deity, first god then goddess, many examples from the Near East rather than simply from Greece, Rome and Northern Europe, an interpretation of lunar cycles as signifying rebirth or immortality and prompting mathematical cosmology, as well as Briffault’s idiosyncratic spelling of the name of the Babylonian moon god, ‘Sinn’, and his description of Ishtar, goddess of the morning and evening star, as a Moon goddess. Harding does not however emphasise Briffault’s theory of witchcraft as early matriarchal religion, and whereas he sees the supposed matriarchal stage of religion as part of a primitive past which evolution has fortunately left behind, Harding uses his examples to illustrate her own Jungian account of the continued importance of the feminine and of the primitive in the functioning of the healthy psyche.

Here then is another chain of derivation of today’s triple Moon goddess, one which may prove to be entirely independent of Graves. Briffault is not listed in the index of Graves’ White Goddess or Greek Myths, nor in those of his biographers, Martin Seymour-Smith, Miranda Seymour and Richard Percival Graves,55 and so it may be that, amazingly, the erudite Graves had not read him.

Conclusion

Two conclusions emerge clearly from this investigation. The first is that Graves and Crowley were not the first to propose a triple Moon goddess in the modern age, but that such a being, known from ancient texts, had already been the subject of lively discussion in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Furthermore, a comprehensive theory of the importance of a moon deity, usually triple, in ‘primitive’ religion and magic had already been published by Briffault in a systematic and influential work some twenty years before Graves.

The second is that far from this goddess being a pure invention of the modern age, the ancient world has indeed left us a substantial number of texts describing a triple Moon goddess, whose importance or otherwise in the broader society of the time remains to be investigated. In particular the association (later identification) of Selene, Artemis, Hekate and Persephone beginning in the fifth century BCE, the possible importance of a Moon goddess at the start of the Roman imperial era, and her re-emergence (or continuance?) in late antiquity, since the ‘three in one’ trinity of Ceres/Proserpina, Luna and Diana is singled out for criticism by Arnobius,56 are all matters which have received little critical discussion since the great nineteenth-century polemics.

Prudence Jones

First published – Prudence Jones, ‘A Goddess Arrives: Nineteenth Century Sources of the New Age Triple Moon Goddess’, Culture And Cosmos, Vol. 9 no 1, Spring 2005 pp. 45-70. Published in Wiccan Rede Online with permission, many thanks to Prudence.

CULTURE AND COSMOS

A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy Vol. 9 no 1, Spring/Summer 2005 Published by Culture and Cosmos and the Sophia Centre Press, in partnership with the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, in association with the Sophia Centre for the Study of Cosmology in Culture, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Faculty of Humanities and the Performing Arts

Lampeter, Ceredigion, Wales, SA48 7ED, UK.

www.cultureandcosmos.org

References

- Janet and Stewart Farrar, The Witches’ Way (London 1984), p.71.

- Starhawk, The Spiral Dance (San Francisco 1979), p. 78.

- Nor Hall, The Moon and the Virgin (London 1980), pp. 1, 3.

- Gerald B. Gardner, The Meaning of Witchcraft (London 1959), p. 133.

- Robert Graves, The White Goddess, a historical grammar of poetic myth (1948, revised edition London 1961) [hereafter Graves, Goddess]; Michael York, The Divine versus the Asurian, Bethesda, Maryland, 1995), p. 387); Miranda Seymour, Robert Graves, Life on the Edge, (New York, 1995) [hereafter Seymour, Graves], pp. 306-7, 311; and Hutton, Ronald, The Triumph of the Moon (Oxford, 1999) [hereafter Hutton, Triumph], pp. 41, 179.

- Prudence Jones, ‘Triads and Trinities’, Pagan Dawn 135: 14-16; 136: 26-28 (London 2000); Ronald Hutton, Witches, Druids and King Arthur (London, 2003), pp.97-8; Prudence Jones, ‘”Aspects” of Deity’, Astrology and the Academy, ed. Nicholas Campion et al. (Bristol 2004), 25-48. 6a. Graves, Goddess, p.70.

- See e.g. summary in Hutton, Triumph, 25-40, 123-125. 7a Graves, Goddess, p.384.

- Seymour, Graves, p. 62, referring to Graves’ Collected Letters I: 66-7. 8a. Graves, Goddess, (p.386). 8b. Pausanias, Description of Greece, VIII 22, 2.

- The Golden Fleece (London, 1944); (tr.) The Golden Ass, by Lucius Apuleius (London, 1950); The Greek Myths (Harmondsworth, (1960; 1st ed. 1955) [hereafter Graves, Myths]; (with Raphael Patai) Hebrew Myths, (London and New York, 1964)

- References to Renaissance quotations of Servius are in e.g. Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance (2nd ed. London 1968) p. 28 no. 5. Schoolroom text: The Aeneid of Virgil, ed. T.E. Page (London & New York, 1967, 1st printing 1894) IV. 511 and 382-3 schol. ad loc.

- J.E. Harrison, Themis (2nd edition 1928; London 1963), p. 408.

- Harrison, Themis, pp. 189-90. 12a. Graves, Myths, chapter 10.1, on the Fates.

- Graves, Myths, p. 14.

- The best fit in Pauly-Wissowa, Real-Encyclopedie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, vol. VI,1 (Stuttgart, 1907), is the sixteenth Epigenes it lists, described as ‘griechischer Grammatiker der alexandrinischen Zeit’, adding that he was older than Callimachus (the poet, fl. 270 BCE), and that his paper on Orpheus was reported by Clement. 14a Clement of Alexandria, Stromata: Abel, frg. 253.

- J.E. Harrison, Mythology and Monuments of Ancient Athens, (London, 1890),

- 373-385, and Themis, p.192 no.4. and Harrison, Themis, p.192, p.392 no.2.

- Aleister Crowley, Moonchild (London, 1929), pp.187-8.

- Gardner meets Crowley: Hutton, Triumph, pp. 216-23; Gardner meets Graves: Seymour, Graves, p.399.

- Aleister Crowley, The Complete Astrological Writings (ed. J. Symonds and K. Grant) (London.1987), pp. 47-8.

- T. Duquesne in Crowley The Rites of Eleusis (Thame, 1990), p. 62.

- Quotations e.g. in Complete Works (London 1905; 1913), p.24 and adaptations e.g. in The Rites of Eleusis p. 102) Hutton, Triumph, ch.2.

- 22a. Paradise Lost VII 247-9. 22b. Astronomica II.906-917. 22c. Tetrabiblos I, 6.

- For early modern astrology see W. Lilly, Christian Astrology, (1647; London 1984), p. 81: ‘[The Moon] signifieth … all manner of Women’. For psychological astrology, see e.g. Alan Oken, As Above, So Below (New York, 1973) p. 260: ‘the female aspect of God [is] the Moon’, Isobel M. Hickey, Astrology, a Cosmic Science (London, 1975), p. 31: ‘the Moon represents … Mother and female influence in a male chart, Femininity’.

- Evangeline Adams, Astrology, Your Place Among the Stars (London, c. 1931), pp. 151-2.

- Israel Regardie, The Golden Dawn (River Falls, Wisconsin, 1970), v.1 p.78.

- ibid. p.132.

- R.G. Torrens, The Secret Rituals of the Golden Dawn (Wellingborough, 1973), p.132. Torrens’ edition claims to give the original, pre-1903 rituals and differs in some respects from Regardie’s version, which is explicitly edited for practical utility..

- Ithell Colquhoun, Sword of Wisdom (London, 1975), pp. 77, 119, 170. For the members in common see also individual biographical passages)

- H.P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine (1888; facsimile edition, Los Angeles, California, 1982), p. 156.

- Ibid. p. 387.

- Ibid. p. 425. 31a. Martial, Epigrams V.1, 2; available in parallel text ed. & tr. D. R. Shackleton Bailey (Loeb edition, Harvard U.P.,1993). 31b. Ibid. IX 64, 3. 31c. Horace, Odes III 22, 4, ed./tr. Niall Rudd (Loeb edition, Harvard U.P., 2004). 31d. Vergil, Æneid VII 516, ed. T.E. Page (Macmillan, London, 1970). 31e. Catullus, poem xxxiv, (G.P. Goold’s revised edition of F.W. Cornish , Loeb, Harvard U.P., 1988) 31f. Varro, de lingua latina VII 16, ed/tr. R.G. Kent (Harvard U.P., 1967).

- Andrew Alföldi, ‘Diana Nemorensis’ in American Journal of Archaeology (1960), vol. 64, 137-144, who provides a list of references to triple Diana among the Golden Age poets, argues that the triple Diana originally ruled over a tripartite division of pre-Roman Italic tribes. For the pomegranate and an argument for Graeco-Etruscan origin see F-H. Pairault, ‘Diana Nemorensis’ in Mélanges d’Archéologie et d’Histoire (1969.2) 425-71. 32a. Vergil, Æneid IV 511, ed. T.E. Page (Macmillan, London, 1967). Image: The Lariscolus coin image is from Alfoldi 1960

- ‘Rex Nemorensis’ (i.e. C. Cardell), Witch, (Charlwood, 1964). 33a. Graves, The White Goddess, p. 255. 33b. Statius, Silvae, III.1.55f (ed. D. Shackleton Bailey, Loeb edition, Harvard U.P., 2003). 33c. Graves, Myths, 101.l (p.358 in the 1960 edition); also 116.c (p.436) and note 4. 33d. Graves Myths 31.f; 31.7 (pp. 122, 124 in the 1960 edition). 33e. Aeneid VI 136, ed. T.E. Page (Macmillan, London, 1970).

- J.G. Frazer, The Golden Bough, (London, 1911-15) [hereafter Frazer, Golden Bough], part 1, The Magic Art and the Evolution of Kings, vol.i. 8; 10;

- Karneios: ibid., 36; in modern Wicca: Vivianne Crowley, Phoenix from the Flame (London, 1994) p. 65, Karnayna.

- Frazer, Golden Bough, part 5, Spirits of the Corn & of the Wild, vol. i, 35-91, 129-70. 36a. Ovid, Fasti III 264 (ed. & tr. J.G. Frazer, rev. G.P. Gould, Loeb edition, Harvard U.P., 1989).

- Graves, Goddess p.9; Myths pp. 9-10.

- Augustus’ reordering of State religion: Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (2nd edition Oxford 1971); dateable commentaries on the three astrological goddesses begin in the middle of the first century CE with Cornutus’ scholium on Theocritus 2.12, see discussion in Jones, ‘Aspects’, 27ff.; Franz Cumont, Astrology and Religion among the Greeks and Romans (republished New York, 1960), Lecture III; Graves is quoted in Seymour Graves p.315 as saying that his studies drew on ‘Babylonian astrology, Talmudic speculation, the liturgy of the Ethiopian Church, the homilies of Clement of Alexandria, the religious essays of Plutarch, and recent studies of Bronze Age archaeology’ .

- E.g. Alföldi, ‘Diana Nemorensis’ p.141 states that the identity of these goddesses was established from the fifth century BCE; contrast Sarah Iles Johnston, Hekate Soteira (Atlanta, Georgia, 1990) p.31 n. 7, on the late amalgamation of Hecate and the Moon.

- Robert, ‘De Gratiis Atticis’ in Essays in Honour of Theodor Mommsen [which I have not been able to trace], mentioned in Harrison, Mythology & Monuments p.382; W.E. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie, (Leipzig1884-1890), col. 1904.

- Roscher, Lexikon, col. 1890); L. Preller (ed. C.Robert), Theogonie und Götter, (vol. i of Griechische Mythologie, 4th ed. Berlin, 1894), pp. 296-7.

- L. Pauly, cont. G. Wissowa, Real-Encyclopedie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (Stuttgart,1912), s.v. Hekate §2778-9; L.R. Farnell (Cults of the Greek States (Oxford,1896) vol. II, 457-61).

- E. Petersen ‘Die Dreigestaltige Hekate’, Archäologisch-Epigraphische Mittheilungen aus Oesterreich ed. O. Benndorf & O. Hirschfeld (Vienna, 1880) [hereafter Petersen, ‘Hekate’], vol. IV, pp. 141-174, (1881), vol. V, pp. 1-84, 193-202, and plates.Image: The Three Graces dancing round a (headless) statue of Artemis/Hekate Epipyrgidia are reproduced from Jane Ellen Harrison’s Mythology and Monuments of Ancient Athens (1890) p.379, taken from Petersen 1881

- Petersen, ‘Hekate’ (2) 39 ff.

- Harrison, Mythology & Monuments, 380-2.

- Harrison, Themis, 408 no.2.

- Dr H. Usener, ‘Dreiheit’, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie (1903) vol. LVIII, 1-47, 161-208, 321-362, mentioned in Harrison, Prolegomena, p.288 no.1. 47a. Usener, ‘Dreiheit’, p.335. 47b. Usener, ‘Dreiheit’ p.347.

- Usener, ‘Dreiheit’, 36-7; cf. e.g. a recent historical account of the construction – ‘not revelation’ – of the Christian trinitarian concept in K. Ohlig, Ein Gott in Drei Personen? (Mainz, 1999).

- Harrison, Themis, page ix.

- Robert Briffault, The Mothers (London, 1927). 50a. Briffault, III.xxiv.46; II.xix.555. 50b. Briffault , II.xix.503. 50c. Briffault, II.xx.599. 50d. Briffault, II.xx.600-3. 50e. Briffault II, p. 606 n. 6.

- Graves, Goddess p.9.

- M. Esther Harding, Women’s Mysteries Ancient and Modern (New York 1955; my edition London 1971).

- Goblet d’Alviella La Migration des Symboles, (Brussels, 1894) [hereafter: d’Alviella, Migration]; Félix Lajard, Sur le Culte de Mithra (1847); Jacob Bryant, A New System or Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1774)

- Harding, Mysteries, fig.33 p.217, commentary p. 216; d’Alviella, Migration

- 224-5 fig. 73 and commentary. Seymour, Graves, as above; Martin Seymour-Smith, Robert Graves, his Life and Works (1982; 2nd edition, London, 1995); Richard Percival Graves, Robert Graves (v.1 London, 1986; v.2 London, 1990; v.3 London 1995).

- Arnobius, Adversus Nationes, iii, 34.