Commentary on Prof. Carlo Ginzburg’s book: ‘Hexensabbat – Entzifferung einer nächtlichen Geschichte’ / ‘ Witches’ Sabbath: Deciphering a Night Tale’ (Wagenbach – revised Mar. 2005)

I recently read Prof. Ginzburg’s book about the witches’ sabbats.

It’s incredibly detailed and leads the reader through a wide range of antique tales as well as many examples of shamanic beliefs from Europe to Asia. It was easy to loose the thread to that what I was actually interested in, which is, the question whether there is some sort of evidence for a practised (witch)cult in Germany (or rather, Central Europe) where a witch cult like Wicca could have been derived from.

I chose Carlo Ginzburg because in books about the witch trials he’s quoted almost everywhere but always cut off from its context. It’s the same with Burchard von Worms. I’m still on the track to find out more about him. (See Silvia’s article in Wiccan Rede Online, “The attitude towards witches in the past and the background of the witch trials in Germany –” link can be found under references)

Prof.Ginzburg adds an exceedingly extensive list of quotations that show that there are very contradicting interpretations and opinions about many things which are concerned with witchcraft and/or any other cultural developments.

The book is called in German ‘Hexensabbat – Entzifferung einer nächtlichen Geschichte’ – the Italian original ‘Storia notturna. Una decifrazione del sabba’. It was first published 1989 but has been revised meanwhile.

It is a reflection on the backgrounds of the practices of ‘witches’ which they admitted during the witch trials – especially at the time when these were not forced by torture but reported more or less deliberately.

It includes an enormous amount of sources from Greek traditions and also of Siberian shamanic traditions. It explains as well how the pogroms against heretics, Jews and later witches came up (starting in France) and builds up a theory of why the belief in witches and fairies spread especially in certain areas like France, the Alps, parts of Germany and Scotland.

The discussion of the backgrounds is based on the files of secular and clerical trials or investigations.

Especially in the earlier period of the Middle Ages people who were accused of having contact with non-Christian groups or practising spells etc. were not necessarily tortured and as cruelly punished as in later times (most of the trials – the really bad ones – in Germany and the neighbour countries took place after the Thirty Years’ War).

This evidence has certain motives in common:

- people reported having fallen into some sort of trance

- they were led by either a dark female person or a goddess (with varying names)

- they describe having changed into an animal

- they admit having eaten human flesh (sometimes parts of themselves)

- they report about the killing of animals

- the goddess or leading person is able to heal the dead afterwards

- they fly or ride to secret meeting places.

(Prof. Ginzburg points out a couple of more aspects but this would go too far here).

The files were written down in comparably late times. So it’s difficult to see proof in them that there was any sort of witch’s cult passed on from pre-Christian times until then. Obviously, this question wasn’t part of the investigation. So Prof. Ginzburg tries to construct a common past by putting these motives and elements together.

He describes the Benandanti as well because they ended up accused of the same things as the witches. They are described as having gone through the same procedure as the witches to get into a trance. The essential difference is that they understood themselves as witch hunters and were sent out to save nature while the witches went around to do harm to men and animals and to destroy the harvest.

Obviously, the witches had already been totally stigmatized during the late Middle Ages. They were definitely the ‘bad ones.’ While the Benandanti were active in Friaul in Italy there have been comparable examples in Slavic countries where werewolves (the good ones) fought against witches. There is no explanation why the witches were reduced to only harming the world around them.

Prof. Ginzburg works out a few points which should be seen in a common mythological context and where parallels seem to exist in unfamiliar cultures.

All the people reported that they fell into a sleep or deep trance caused by a drink. Many added as well that they were very thirsty and needed to drink a lot when they ‘came back’. Then they were led by a dark woman to whom they were connected, with different names like Richella, Artemis, Diana, etc. (depending on the different areas) to a strange meeting place. They used to fly or ride there.

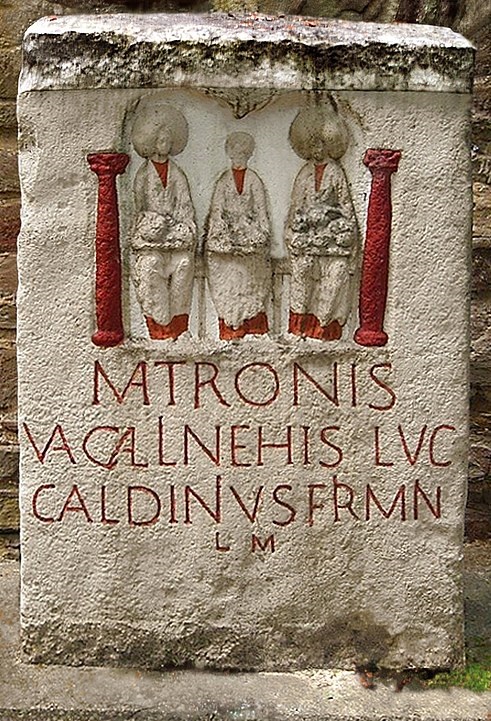

Because of the characteristics featured Prof. Ginzberg assumes an old cult of matrons (there are a couple of statues of them especially in the west of Germany and in the countries around especially where the Romans settled).

Foto: Mediatus, 30. Juni 2010, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Weyer_(Mechernich)_-_Weihestein_des_Caldinius_Firminius.jpg

A problem appears when looking for a link between Artemis/Diana and similar Mediterranean goddesses because they, the matrons, were not connected to horses/ riding and/or to flying. He sees a sharing of characteristics towards the goddess Epona who was honoured in the Celtic parts of western Europe including the southwest of Germany. She is seen as a horse goddess (and of bigger cattle) besides other characteristics, and she was well known all around Europe. Concerning her symbols, she is a fertility goddess as well.

Following Prof. Ginzburg, there are aspects coming together which indicate an old cult of the dead. The persons who take part in the meetings have to travel to the underworld to go through a sort of initiation, to sacrifice and to be led by the goddess, to be born again.

Another hint is the imaginary eating of humans or drinking their blood. Not only in European but in shamanic traditions, far beyond, is the giving back of life to a person (or animal) killed beforehand and the typical characteristics of divine power. In many fairy tales, people/animals get killed or are trapped in a place and as soon as they are touched with a magical item (like a wand) they come back to life. Especially the motive of bones, sewn into an animals skin, appears quite often. They come back to life as soon as the goddess touches them with a magical tool. In many cultures, people who are born with the placenta/amniotic membranes still wrapped around their heads are said to have extraordinary qualities. This is called being ‘being born with a caul’ and is seen as a sign of good luck for both baby and parents. Parents and midwives in some cultures even dried and saved the caul as a good luck charm. According to Prof. Ginzburg, these motives are strongly connected.

Also according to Prof. Ginzburg, witches symbolize the underworld and the realm of the dead in the old traditions and are connected with the transition to another life. Like fairies, they were always connected to milk and blood, both essential for survival. It was a common thing to blame them for turning the milk sour. The animals in this tradition symbolized these processes.

They were especially active during the time between Christmas and New Year, this time being especially connected with the dead. It is a period that had an important significance in many cultures.

There seems to be a connection to still existing customs of dressing up as animals (like the Krampus figures e.g. people dress up as witches and animals, at Carnival for example, although this takes place later than the New Year festivities.

Prof. Ginzburg sees the origins of the death cult in Greek myths primarily and in shamanic rites in diverse places about the same time. In his opinion, these beliefs and traditions came together because the Scythians who were in contact with both transferred the traditions to the Celtic people. He thinks there are aspects of some archetypical transition as well as an oral passing on between the diverse cultures. These survived in cults in areas that were influenced by the Celts in the first place.

Apart from that during the Middle Ages, several groups of society became stigmatized. These were heretics who followed the Jews, who were in the first place. But after a while, the accused followers of the old cults were blamed as meeting at sabbats as well. Prof. Ginzburg sees an especial accumulation of witches’ trials in Celtic areas.

It’s difficult to see religion on its own in the examples which are described in the book. The process of death and rebirth on its own doesn’t make much sense without any context.

Nowadays we know that a long time before Christianity, there were shamans in western Europe as well, wandering in all directions and were in contact with each other. So there are more sources for spreading religious beliefs than the Celts.

It remains strange as well, as to why witches only seemed to have caused harm. I think this can’t be the centre of a cult. Why should it be so and what for?

After all, I think that we still don’t know whether there was a sort of religion that survived from olden times, the death cult being only a part of it. It is possible as well that only this part was still practised without further connection to anything else. It seems that the people who described to have taken part in flying said that something made them do it as if they were forced and didn’t follow it altogether voluntarily. There doesn’t seem to be a religious or philosophical background.

On the other hand, it has to be considered that all these things were written down by the people who accused them of having committed a crime, so they were not really willing to say much more.

Many documents were written many centuries after Burchard von Worms for example, and many details may have been lost. It can’t have been in the interest of any officials to admit that there was an existing death cult around ancient pagan goddesses. The Christian system couldn’t allow some sort of religious subculture.

In my opinion, it is strange as well that groups like the Benandanti and the accused witches used the same methods to get in trance. It seems that the only difference between them is the intention of their actions. The reasons for that are not really obvious.

In conclusion, I think that Prof. Ginzburg’s theories sound very plausible concerning the death cult and the belief about a goddess leading the humans (devil and demon worship appeared later). But I don’t think there is proof for a goddess and witch cult influenced by the Celts as an organized religious system. There may have been one, but we can’t be sure. And if there was one, I think essential elements must have been lost.

We also have to consider that Prof. Ginsburg’s book was written some decades ago. Meanwhile, we know much more about where and when different tribes of people were in contact. So there are certainly more aspects which have to be considered. And it will remain interesting what is still to be found out.

Nevertheless, his theories may lead us to have another look at some Christian as well as Pagan customs, such as the Eucharist, or even the Wiccan ceremony of Cakes and Wine. The (re)search goes on.

Silvia Schwikart, 13.04.2021

References:

** Silvia Schwikart: The attitude towards witches in the past and the background of the witch trials in Germany –

The attitude towards witches in the past and the background of the witch trials in Germany