Since times immemorial the summer solstice has been celebrated with bonfires. They were kindled on the night of Saint John, 23 June. Often, the ceremony included rolling a burning wheel from a slope, which signified the waning sunlight. From now till midwinter, the days shorten. Sometimes a straw effigy or a pole was burnt in the fire. According to James Frazer, the puppet has been called Lotter, Luther, Angelman, Tatermann.

Superstition holds that the fire drives away witches and diseases. In a positive sense, it makes crops grow. Extinguished branches from the fire were taken home for protection.

Quite often, aromatic herbs were burnt in the fire. These mainly included Mugwort and Vervain. On the Continent, Mugwort has always been part of traditional herb chaplets. These were gathered around Midsummer and contained either seven or nine herbs. Wreaths like this are known as wis in Dutch and Wisch in German. The wreath was hung in the house for protection. In times of need, the herbs were burnt in the hearth. Mugwort and Vervain also feature prominently in the Anglo-Saxon Nine Herb Charm. It is noted that Mugwort contains trance inducing substances and has always been Europe’s native incense.

The summer festival is held all over Europe, but in Sweden the celebration was known as Balder’s Balar. Frazer records and translates it as ‘Balder’s balefires’. Balar is a plural noun derived from Old Norse bál, meaning funeral pyre. Its primary meaning is flame. The word may be the origin of the morpheme bel in beltaine. It looks like the puppet burnt in the fire represented Balder.

The Story

The story of Balder’s pyre is recorded at the end of Gylfaginning as an introduction to the events of Ragnarok. In the poetic Edda, it is told in Baldrs Draumar, and it is referred to in Voluspa, stanzas 31-33.

The story begins with Balder’s dreams. He relates them to his father, upon which Odin calls a Thing. According to Snorri, the moot decides to protect Balder (baldr). He is made immune (grið) from all danger. Frigg takes it upon her to go around and request oaths of harmlessness from everything in existence.

Baldrs Draumar 1

ok um þat réðu ríkir tívar,

hví væri Baldri ballir draumar.

And about this counselled the mighty gods

Why did Balder have bad dreams

In the poetic version, the moot results in Odin’s journey to the World of the Dead, alternately called Niflhel and Hel. He goes there to conjure up a Volva and interrogate her on the meaning of his son’s dreams. The Volva explains that the goddess of the dead is preparing Balder’s arrival.

The divinations of the Volva go as follows.

Odin: “For whom are the benches sown with rings, the floor fairly flooded with gold?”

Volva: “Here stands for Balder the brewed mead; over the bright drinks lie the shields”

Odin: “Who shall Balder’s slayer become and of Odin’s son rob his life?”

Volva: “Hoder bears the high and proud beam; he shall Balder’s slayer become”

Odin: “Who will avenge Hoder’s act. Or send Balder’s slayer to the funeral pyre?”

Volva: “Rind bears Vali in the West Halls. So shall Odin’s son, one night old, fight. Hands will wash nor head will comb until to the pyre he bears Balder’s adversary”

Snorri continues. Loki is jealous of Balder’s invulnerability and works a scheme to kill him. He persuades Frigg to tell him her secret, and she says that the mistletoe can still harm her son. Loki finds the twig and shapes it into an arrow or spear.

In the meanwhile the Aesir are making sport of Balder by hitting him with everything they got. Loki arrives at the scene and sees how Hoder (höðr) waits outside the side-line. He approaches him and gives him the mistletoe missile. Then he helps Hoder aim, since the god is blind. Hoder shoots and kills Balder.

Snorri’s version is quite long and continues with a plea to Hel to return the slain god. But this plan fails. Simultaneously, a funeral pyre is prepared. In the Eddic poems, the pyre is prepared not for Balder but for Hoder. In each case, the fire is termed bál. In addition, the Eddic poems make no mention of Loki. Each time, Hoder takes the mistletoe and shoots.

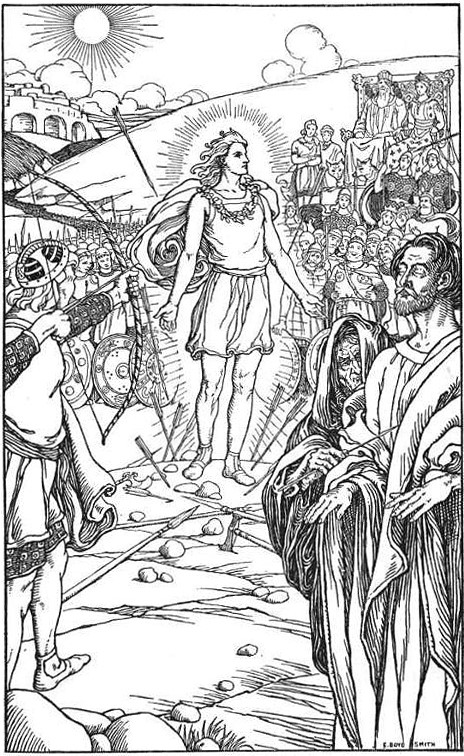

(“Each arrow overshot his head” (1902) by Elmer Boyd Smith.)

Voluspa 31-33

I saw Balder, the bloodied war god

Odin’s kid, his destiny hidden

Stood waxed on the high fields

Slim and very fair the mistleto

Became of that gallows, looking slim,

A harmful arrow. Hoder took to shooting

Balder’s brother was born soon

So took Odin’s son, one night old, to fighting

He did not wash hand nor combed head

Until to the pyre he bears Balder’s adversary

But Frigg wept in the Fen Halls

For Valhalla’s woe

The Voluspa passage focuses on the mistletoe. The last line of stanza 32 and the first half of stanza 33 look almost exactly like the corresponding stanza in Baldrs Draumar, stanza 11 (sá mun Óðins sonr einnættr vega: hönd um þvær né höfuð kembir, áðr á bál um berr Baldrs andskota).

The poems claim that Balder’s death will be avenged by a son of Odin, “one night old”. In Baldrs Draumar he is identified as Vali. No mention of this is made in Gylfaginning, but a parallel is found in Saxo’s Gesta Danorum. Saxo’s myth explains how Odin fathers Vali.

(The death of Baldur ‘the Fate of the Norns’. Natasha Illincic)

Nightmares

Bad dreams, mistletoe and death are a foreboding triad found outside the Balder myth. In folklore, nightmares are caused by a spirit known as the Mare. It is usually a young girl, though sporadically a man. In Dutch, she is known as the maar or mare; in German, die Mahr. Heimskringla mentions a demon Mara. And this name forms the basis of the French word for nightmare, cauchemar.

What happens is this. The victim wakes up suddenly in the night and can’t move. He feels a heavy weight press down on his chest. He wants to scream but he cannot. According to folk tales, horses often suffer the same. The expression goes “to be ridden by the Mare”; in Dutch “van de mare bereden”.

The most common remedy consists of holding a knife on the chest when going to sleep. In every single tale, the advice is given to hold the knife point down, but the victim invariably interprets this in the wrong way and holds it point up. In the morning, a neighbour is found dead, usually a woman. She appears to have been stabbed in the heart. Sometimes the Mare drops dead on the victim using this procedure. More generally, it has also been whispered that a visit of the Mare herald’s death in the community. In Heimskringla, the appearance of Mara becomes the victim’s own death (Ynglingasaga 13).

I myself have been ridden by the Mare twice. Each time I woke in the middle of the night, only to realize that I was unable to move. The first time I panicked, but not the second time, because I knew it would pass. Afterwards I understood that the sensation of paralysis is real, because what happens is that you wake up during that time of the sleep cycle when the body is paralyzed. Each time, too, in the morning I heard the news that someone had died that night. Both times it was a famous public person.

The second most common means to rid oneself of the demon is to place your slippers or shoes in front of your bed wrong-footed. Prayers, too, have come down to us. The prayers and the trick with the shoes are typical of confusing witches.

I list two of the prayers.

- Dutch original

Mare, mare, ‘s avonds rijdt de mare

Sint-Pieter, kunde gij:

Houd de mare ver van mij

En ‘k wete, dat gij het kunt

‘k vrage dat gij het mij ook gunt

Daarom, eer dat ‘k slapen ga

Help mij aan die Gods gena:

Dat de mare rijen mag

Over elke heg en haag

Over al de pijlen gras

Waar dat ze dus moe van is

Over al de planten en stokken

Eer dat ze aan mijn bedde gerokken

- English translation

Mare, mare, at night rides the mare

Saint Peter, you are able:

Keep the mare far from me

And I know you are able

I ask that you allow me this

That’s why before I go to sleep

Help me to receive God’s grace:

May the mare ride

Over each hedge and row

Over all the blades of grass

And this will tire her

Over all the plants and stalks

Before she reaches my bed

- Dutch original

Nachtmaar, jij lelijk dier

Blijf vanavond ver van hier

Alle wateren moet je waden

Alle bomen moet je ontbladen

Alle grasjes moet je tellen

Kom mij deze nacht niet kwellen

- English translation

Nightmare, you ugly beast

Stay away from here tonight

All the waters you must wade

All the trees you must unleaf

All grass you must count

Don’t torment me tonight

Other means included nailing a horse shoe on the stable, or either two bricks in the shape of a cross, or mistletoe. The latter is significant, because the plant is called maretak in Dutch, meaning ‘mare-twig’, and therefore referring to the Nightmare. Sometimes a pentagram is used to ward off the demon. This symbol was called marevoet in Dutch. But what’s most important is that the very name of the mistletoe plant reveals an innate connection with the Nightmare lore.

In German speaking countries, bad dreams are called Alptraum or Alpdrücken. The first means ‘elf dream’ and the second ‘elf pressure’. The latter refers to the sensation of paralysis. The German words indicate that we are dealing with an elf of sorts. German folklore further associates the Nightmare with the Drude, which is a kind of elf. Drudenfuss is a German name for the pentagram and it is rendered in Dutch as droedenvoet. We therefore conclude that the Mare is a Drude.

The name of this class of beings is derived from Old Norse þrúðr which is usually translated with ‘strength’ because it is associated with Thor. His hammer is called þrúð-hammar in Lokasenna. Moreover, Thor’s daughter is called Thrud. Alternatively, the word may derive from ‘to tread’. Also, according to folklore, the mistletoe berries are sacred to Thor. They are called Donnerbesen in German.

I cannot help but think that Thrud would be the Nightmare, the daughter of Thor. In Alvissmal she is associated with both dwarves and night. Dwarves were associated with elves.

Mistletoe

The mistletoe plays a prominent role in Balder’s story. Indeed, it causes his death. This is in stark contrast to the protective properties attributed to the plant. First and foremost, the mistletoe is a healing plant. It was called all-heal by the Druids. Secondarily, it is carried on the body or hung in the house for protection. It particularly protected against fires, reminiscent of Havamal’s magical spell number 7. It says: “If I see a high fire on the hall of my seated mates, however wide it burns, I help them.” Last but not least, we have seen that the mistletoe protects against bad dreams. It would drive away the cause of death.

The plant’s positive function leads Frazer to identify Balder with the oak tree. Mistletoe that grew on oak was held in the highest regard. Frazer postulates that tearing the parasite from the tree equals tearing the life from it. In my own opinion, the function of the mistletoe may have become confused. I would speculate that Frigg used the mistletoe to protect Balder from the Nightmare. Later it became the instrument of his death.

But there is third vista. Greek mythology associates the plant with Persephone. According to the myth, mistletoe was used to open the gates of the Underworld. By the virtue of this plant, Persephone was able to both enter and leave Hades. The Roman episode of Aeneas reads in a similar way. In the story, Aeneas carries a virga aurea or Golden Bough to vouchsafe his return from the Underworld when he visits his father Anchises. Must we presume that Balder carried the mistletoe to safely enter Hel?

Let’s recapitulate the myth of Balder’s death against the backdrop of nightmare and mistletoe lore.

When Balder suffers bad dreams he is visited by the Mare. Consequently, mistletoe is gathered to avert the evil eye. Maybe a weapon was made from the twig and held to Balder’s breast. Either he held it himself or Hoder did, but in any case the sharp end must have touched his body and maybe caused his death. Balder is now in possession of the mistletoe and therefore able to enter Hel, maybe alive. Indeed, he will leave the Underworld alive when the time comes. The mistletoe gives him this ability.

I would conclude that the mistletoe originally performed its protective function. It guards Balder when he visits the Underworld, so that he may return after Ragnarok alive and well.

Myth and Reality

Now let’s return to the Midsummer festival. The god’s dying is associated with the summer solstice; the disappearing light symbolizing Balder’s death. His eventual return is associated with the winter solstice. When the god leaves the Underworld, at midwinter, the light increases again. According to the myths, Balder leaves Hel after Ragnarok is waged. The war is associated with winter (fimbulvetr).

That leaves Hoder. He is Balder’s brother and the alleged cause of his death. However, Hoder is blind, and thus metaphorically ignorant of the consequences of his actions. The myths relate that another son of Odin must be born to exact vengeance. This is Vali and he will kill Hoder. Notwithstanding, Hoder will leave the Underworld after Ragnarok, too.

In my opinion, Balder and Hoder each stand for one half of the year. Balder rules from Midwinter to Midsummer and represents the light. Hoder rules from Midsummer to Midwinter and represents the darkness. As such, they resemble the oak king and the holly king of contemporary Celtic thought.

(Death of Baldur)

Vincent Ongkowidjojo

Bibliography

- C.J. Bultink, Verhalen uit de Nederlandse verteltraditie, in Draken en andere vreemde wezens, Lemniscaat, Rotterdam 1991.

- Cleasby & Vigfusson, An Icelandic-English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1957.

- Marcel De Cleene & Marie Claire Lejeune, Compendium van Rituele Planten in Europa, Mens & Cultuur Uitgevers, Gent 1999.

- James Frazer, The Golden Bough, abridged edition, Penguin Books, 1996 (original from 1922).

- Lee Hollander, History of the Kings of Norway, University of Texas Press, Austin 1992.

- Vincent Ongkowidjojo, Secrets of Asgard, Mandrake, Oxford 2011.

- Roeck, Volksverhalen uit Belgisch Limburg, Het Spectrum, Antwerpen 1980.

- Renaat van der Linden & Lieven Cumps, Volksverhalen uit Oost- en West-Vlaanderen, Het Spectrum, Antwerpen 1979.

- A.F van Veen & Nicoline van der Sijs, Groot Etymologisch Woordenboek, Van Dale, Utrecht/Antwerpen 1997.

- Wahrig Herkunftswörterbuch, Wahrig, München 2009.

Images:

“Each arrow overshot his head” (1902) by Elmer Boyd Smith.: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baldr#/media/File:Each_arrow_overshot_his_head_by_Elmer_Boyd_Smith.jpg

The death of Baldur ‘the Fate of the Norns’.. Natasha Illincic: https://natasailincic.deviantart.com/art/The-Death-of-Baldur-535945597

Death of Baldur: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baldur#/media/File:S%C3%81M_66,_75v,_death_of_Baldr.jpg