It’s not clear how old the tradition of ‘Telling the Bees’ really is. It was very much in the news recently however when, “After the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the Royal Beekeeper, John Chapple, informed the bees of Buckingham Palace and Clarence House of her passing and the ascension of King Charles III. Chapple described the practice to the press as such:

“Speaking from the Buckingham Palace gardens, Mr Chapple told MailOnline: ’I’m at the hives now and it is traditional when someone dies that you go to the hives and say a little prayer and put a black ribbon on the hive. I drape the hives with black ribbon with a bow. The person who has died is the master or mistress of the hives, someone important in the family who dies, and you don’t get any more important than the Queen, do you?

You knock on each hive and say, ‘The mistress is dead, but don’t you go. Your master will be a good master to you.’ I’ve done the hives at Clarence House and I’m now in Buckingham Palace doing their hives.’

(The bees have also been told, in hushed tones, that their new master is now King Charles III Draping the hives with black ribbons)

In nineteenth-century New England, it was held to be essential to whisper to beehives of a loved one’s death.

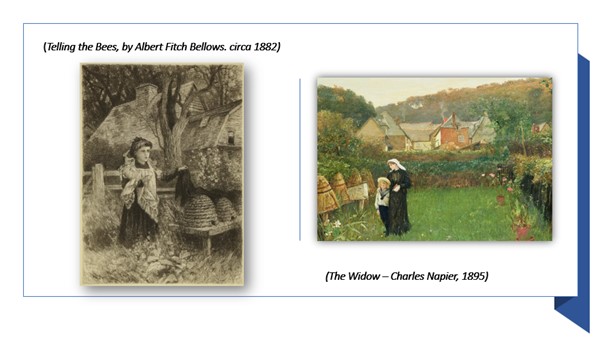

Telling the Bees, 1879

“Following a death, the list of duties seems endless. From booking the undertaker to choosing the coffin, plot or crematorium, the list of necessities seems endless. But of all of these commitments, the most important of them, the most integral of all, is telling the bees. It’s a matter of tradition, you know.

Across the UK and Europe, it has been a long-standing tradition for beekeepers to inform their hives of changes and important developments in their lives. Everything within the life of the beekeeper, from births, deaths, weddings and christenings; even changes in the household and the arrival of visitors, had to be conveyed to the bees. If the bees were not informed, all hell would break loose in the hives; the bees would stop producing honey, leave their homes or simply die. These superstitions were built upon the belief that beekeepers and their hives had a strong emotional bond, and so should be informed with the same courtesy extended to a family member.”

In one instance, after a call for ‘turn the hives’ was made, the naïve servant, unaware of the meaning of the phrase, lifted the hives and put them on their sides. Immediately, the bees swarmed the poor servant, the pallbearers, horses, and attendants, pursuing them as they fled.

One method of informing the bees of their owner’s death was for his ‘eldest son, or his widow, to strike the hives three times with the iron door key and say, ‘The master is dead.’’ Following this, the hives were put into mourning, either by draping them in black crepe or by tying pieces of crepe around them.

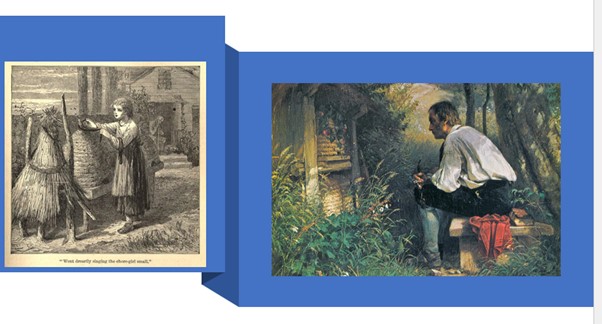

In a 1901 work by Samuel Adams Drake, the process of putting the bees into mourning is described as having the widow attend to the bees and hanging the stand of hives with black, the usual symbol of mourning, at the same time softly humming some doleful tune to herself.

A few stanzas of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem ‘Home Ballads’ captures this tradition:

Before them, under the garden wall,

Forward and back

Went, drearily singing, the chore-girl small,

Draping each hive with a shred of black.

Trembling, I listened; the summer sun

Had the chill of snow;

For I knew she was telling the bees of one

Gone on the journey we all must go!

“Stay at home, pretty bees, fly not hence!

Mistress Mary is dead and gone!”

Whittier himself was eager to locate the tradition of “telling the bees” within the folklore of rural New England. When he published the poem in the Atlantic in 1858 he included an introduction to the poem where he notes that this ritual that has “formerly prevailed” was brought to America from “the Old Country”. That Whittier felt it necessary to include a note about this tradition indicates that, even in the mid-nineteenth century, the tradition of “telling the bees” was fading.

In an 1858 letter to fellow poet and Atlantic contributor Rose Terry Cooke, Whittier mentions that, following the advice of the Atlantic’s first editor, James Russell Lowell, he changed the title to “Telling the Bees” and added a verse “for the purpose of introducing this very expression.” Whittier’s comments, and his introductory note, indicate a desire to preserve this particular folkloric ritual, to educate the unaware. The emphasis that Whittier places on this concept of delivering important information to the bees implies that there is a special relationship that exists between honeybees and humans that is essential to maintain.

This practice of “telling the bees” may have its origins in Celtic mythology where the presence of a bee after a death signified the soul leaving the body, but the tradition appears to have been most prominent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the U.S. and Western Europe. The ritual involves notifying honeybees of major events in the beekeeper’s life, such as a death or marriage.

While the traditions varied from country to country, “telling the bees” always involved notifying the insects of a death in the family—so that the bees could share in the mourning. This generally entailed draping each hive with black crepe or some other “shred of black”. It was required that the sad news be delivered to each hive individually, by knocking once and then verbally relaying the tale of sorrow.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMz5pXT7uHo&t=99s

This is a rare clip from the 1920’s of how a Dutch beekeeper is telling the bees of a death in the family. He walks to the hives, smoking a pipe, and a black cloth is draped over one of the hives. He taps on each of the hives to get the bees’ attention to tell the news. In Holland, it was customary to use a pipe as a smoker to calm the bees.

Historical Honeybee Articles, “In many places there is a beautiful tradition that Bees are considered part of the family and must be informed therefore of all family deaths and special events. Superstition tells us; if their master dies, they must be told and put into mourning, for if this is not done, they will pine away and die, or abandon their hives and fly away. The formula for telling the bees varies little from place to place; A family member walks sombrely to the bees, with becoming reverence and sorrow a piece of black crape is draped over the hives to put the Bees in mourning, -for the bees are supposed to have sorrow upon sorrow on account of the death of their master. Like their masters’ friends and relations, they must, as they do, wear the signs of mourning. The informant informs the bees by tapping three times on each hive with the house key and says; “Bees, Bees, Bees, your master is dead,” He then says; “your new master is ________.” Superstition holds that it is bad luck to purchase Bees of a dead man, so the Bees are always given to their new master.”

If a family member dies, the bee master will inform the bees by the degree of relationship only, as your master’s brother, sister, aunt, &c., is dead. In Devonshire, telling the Bees was considered such vital importance that a correspondent of ‘Notes and Queries’ tells us: “I once knew an apprentice sent back during the funeral precession by the nurse to tell the bees, as it had been forgotten.”

At the funeral feast, ‘sugar, or biscuits soaked in wine, or samples from the dishes served to the mourners, were taken to the bees’.

The death of a beekeeper was a closely watched thing. In Lincolnshire, the bees were monitored following a death; if they were easily moved, they were happy and had accepted their new home. Should the bees leave, it was a sign that they had been called to their master.

When not grieving, bees were also seen to be omens of death. If a hive were to die without cause, it signalled death to the owner, yet if the bees left the hive to swarm around dead wood, it signified the imminent death of another. This death may be a family member of the hive owner, or simply someone unfortunate enough to be passing by and see the bees.

The roots of these superstitions are unclear, but one argument is that bees were used as an early form of divination. In a letter within The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1811, it was said that in Yorkshire, following the changing of the calendar, bees would hum to signal the correct Christmas Eve and the imminent anniversary of the birth of the saviour.”

For a time, bees were seen interchangeably with butterflies as a symbol of the immortal soul. There are apocryphal instances of bees leaving and re-entering the mouths of sleepers (don’t have nightmares), and to kill the bee or prevent it from re-entering would signal the death of the individual.

While these traditions have become virtually obsolete in modern Western society, our relationship with bees is changing and growing at great speed. Owing to the ongoing bee crisis, more people are approaching tired bees with tiny teaspoons of sugar water and interests in preservation are on the increase. In 2018, French beekeepers staged a mock funeral in Paris, protesting the use of pesticides that they attributed to the deaths of thousands of bees.

While we may not all share a desire to become apiarists, it would not surprise me to see a stark change in our interactions with bees saw hives cropping up across the country, with mascots and children’s cartoons taking on a distinct yellow and black tinge.”

What do we know about bees and where could this tradition come from?

Bees… Symbolism and Mythology

The bee, found in Ancient Near East and Aegean cultures, was believed to be the sacred insect that bridged the natural world to the underworld. Appearing in tomb decorations, Mycenaean tholos tombs were even shaped as beehives.

Bee motifs are also seen in Mayan cultures, an example being the Ah-Muzen-Cab, the Bee God, found in Mayan ruins, likely designating honey-producing cities (who prized honey as the food of the gods).

The bee was an emblem of Potnia, the Minoan-Mycenaean “Mistress”, also referred to as “The Pure Mother Bee”. Her priestesses received the name of “Melissa” (“bee”).

Mt. Ida, the tallest mountain on the island of Crete, has been highly significant to the honeybees for millennia. According to mythology, the goddess Rhea chose to protect her unborn baby from its father, Chronos, who made a practice of eating her babies after he was warned that an heir would kill him. The pregnant goddess hid inside a cave beneath Mt. Ida where she gave birth to Zeus. The babe was suckled by the goat goddess and fed honey by the Melissa bee priestesses. Later, when he became the ruler of the world, Zeus showed exceptional gratitude to his custodians. He placed the melissae among the stars, and to the bees that had produced the honey, especially for him, he gave the golden colour as well as the strength to resist the harsh mountain climate.

Around 2,700 years ago, a temple site grew at a place named Eleuthrena within view of Mt Ida’s summit, only 10 miles away from the sacred cave of Zeus. Very recently, marvellous archaeological discoveries suggest that a thriving bee priestess culture existed at Eleuthrena! (Also known as Apollonia.) In addition, priestesses worshipping Artemis and Demeter were called “Bees”.

Artemis of Ephesus

This Artemis is known as the “Queen Bee Goddess.” An ancient goddess associated with knives, swords, axes, and bees. Her image is that of a female body covered with rounded mounds which are thought by some to be female breasts and by others as beehives, or even bull’s testicles.

At Eryx, the high priestess of Aphrodite was called Melissa (“Bee”). One of the attributes was a golden honeycomb. Bees have been a symbol of rebirth since the Neolithic Age. Melissa enabled souls to be born again. Also in Ephesus, the bee was one of Artemis’ animals; bees are pictured here in her clothes. The Ephesian Artemis was also identified with Rhea in Crete; the buzzing of bees played a role here in mythology to disguise the birth of the child Zeus. Bees had the same meaning as butterflies, who also took in the souls of the deceased until they found a home elsewhere. The way it was depicted in the Neolithic era is reminiscent of the later labrys, the double axe that was a symbol of the goddess throughout Asia Minor and Crete.

“The labrys symbol has been found widely in the Bronze Age archaeological recovery at the Palace of Knossos on the island of Crete. According to archaeological finds on the island, this double-axe was used specifically by Minoan priestesses for ceremonial uses. Of all the Minoan religious symbols, the axe was the holiest. To find such an axe in the hands of a Minoan woman would suggest strongly that she held a powerful position within the Minoan culture.

Women today, especially those who are not afraid of expressing their own opinion regardless of whether it coincides with the whims of others, have often been referred to rudely, as “old battle-axes”. When the above information about the sacred labrys is taken into consideration, this alleged “insult” actually could imply something completely different – an aspect of “cultural memory” as Abby Willowroot points out.

The Delphic priestess is often referred to as a bee, and Pindar notes that she remained “the Delphic bee” long after Apollo had usurped the ancient oracle and shrine. “The Delphic priestess in historical times chewed a laurel leaf”, Harrison noted, “but when she was a Bee surely she must have sought her inspiration in the honeycomb.”

“Tradition holds the famous Delphic Oracle was revealed by a swarm of bees, and the Pythia or divinatory priestesses in Delphi’s temple of Apollo were affectionately called ‘Delphic Bees’, while virgin priestesses of Greek Goddesses like Rhea and Demeter were called melissai, ‘bees’; the hierophants essenes, ‘king bees’. Great musicians and poets like Pindar were inspired by the Muses, who bestowed the sacred enthusiasm of the logos, sending bees to anoint the poets’ lips with honey (Ransome 1937). Some hold the vatic revelations of the Pythia were stimulated by inhaling visionary vapours of henbane, Hycscyamus niger L., issuing from a fumarole over which the Delphic Bees were suspended, and into which the plant had been cast (Ratsch 1987).”

Ernst Neustadt, in his monograph on Zeus Kretigenes, “Cretan-born Zeus,” devoted a chapter to the honey-goddess Melissa.

“Melissa is a given name for a female child. The name comes from the Greek word μέλισσα (melissa), “honey bee”, which in turn comes from μέλι (meli), “honey”. In Ireland it is sometimes used as a feminine form of the Gaelic male name Maoilíosa, which means “servant of Jesus.” Melissa also refers to the plant known as lemon balm (family Lamiaceae; genus and species Melissa officinalis).

According to Greek mythology, perhaps reflecting the Minoan culture in making her the daughter of a Cretan king Melissos, Melissa was a nymph who discovered and taught the use of honey and from whom bees were believed to have received their name. She was one of the nymphic nurses of Zeus, sister to Amaltheia, but rather than feeding the baby milk, Melissa, appropriate for her name, fed him honey. Or, alternatively, the bees brought honey straight to his mouth. Because of her, Melissa became the name of all the nymphs who cared for the patriarch god as a baby.

Ancient Greek Mythology

The name “Melissa” has a long history with roots reaching back to even before Ancient Greece. For this reason, in part, there are several versions of the story surrounding the mythological character Melissa, especially in how she came to care for the infant Zeus. In one version, Melissa, a mountain nymph hid Zeus from his father, Cronus, who was intent on devouring his progeny. She fed Zeus goat’s milk from Amalthea and fed him honey, giving him a permanent taste for it even once he came to rule on Mount Olympus. Cronus became aware of Melissa’s role in thwarting his murderous design and changed her into an earthworm. Zeus, however, took pity and transformed her into a beautiful bee.

Nymphs, such as Melissa, played an important role in mythic accounts of the origin of basic institutions and skills, as in the training of the cultural heroes Dionysos and Aristaeus or the civilizing behaviours taught by the bee nymph. The antiquarian Mnaseas’ account of Melissa gives a good picture of her function in this respect. According to folklore, Melissa first found a honeycomb, tasted it, and then mixed it with water as a beverage. She taught her companions to make the drink and eat the food, and thus the creature was named for her, and she was made its guardian. This was part of the Nymphs’ achievement of bringing men out of their wild state. Under the guidance of Melissa, the Nymphs not only turned men away from eating each other to eating only this product of the forest trees but also introduced into the world of men the feeling of modesty.

In addition, the ancient Greek philosopher Porphyry (AD 233 to C. 304) wrote of the priestesses of Demeter, known as Melissae (“bees”), who were initiates of the chthonian goddess. The story surrounding Melissae tells of an elderly priestess of Demeter, named Melissa, initiated into her mysteries by the goddess herself. When Melissa’s neighbours tried to make her reveal the secrets of her initiation, she remained silent, never letting a word pass from her lips. In anger, the women tore her to pieces, but Demeter sent a plague upon them, causing bees to be born from Melissa’s dead body. From Porphyry’s writings, scholars have also learned that Melissa was the name of the moon goddess Artemis and the goddess who took suffering away from mothers giving birth. Souls were symbolized by bees, and it was Melissa who drew souls down to be born. She was connected with the idea of periodic regeneration.

The Homeric Hymn to Apollo acknowledges that Apollo’s gift of prophecy first came to him from three bee maidens, usually identified with the Thriae. The Thriae was a trinity of pre-Hellenic Aegean bee goddesses. The embossed gold plaque (illustration above right) is one of a series of identical plaques recovered at Camiros in Rhodes dating from the archaic period of Greek art in the seventh century, but the winged bee goddesses they depict must be far older.

Killing the bees… killing ourselves…

The plight of the bees has in recent years become headline news, along with climate change. However, in the case of the bees, it’s not just a result of climate change but a lack of understanding about biodiversity. Had we understood the tradition of ‘telling the bees…’ but also ‘listening to the bees…’ we might not be in the predicament we now find ourselves in. Fortunately, there have been luminaries who have understood the true nature of bees.

Andrew Gough: writing about Anthroposophist, Rudolph Steiner, who was “an Austrian philosopher and esotericist who in 1923 presented a series of nine celebrated lectures on the Bee. Steiner was an esoteric master and a social thinker like few before him – or after – and believed that Bees were models of all that was important in life. His fascination, if not obsession with the Bee was evident as early as 1908 when he spoke in Berlin about the significance of the Bee relative to man;

“The consciousness of a Beehive, not the individual Bees, is of a very high nature. Humankind will not obtain the wisdom of such consciousness until the next major revolutionary stage – that of Venus – which will come when the evolution of the earth stage has finished. Then human beings will possess the consciousness necessary to construct things with a material they create within themselves.”

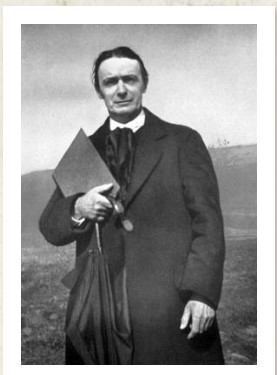

(Rudolph Steiner: philosopher, literary scholar, educator, artist, playwright, social thinker, and esotericist)

Gough continues, “In his superb collection of nine lectures, simply entitled ‘Bees’, Steiner predicted in 1923 that the newly introduced technique of breeding Queen Bees using the larvae of Worker Bees would mean that “a century later all breeding of Bees would cease.”

100 hundred years later – 2023 – the plight of the Bees is far from over. Whilst there is a greater understanding of the need for biodiversity and the banning of pesticides, insecticides and so on the battle for the survival of the bees (and other pollinators) is more important than ever.

As noted earlier, “bees were also seen to be omens of death”. If unheeded we shall die and shall not evolve. Today more than ever we should not only ‘tell the bees…’ we should have a regular ’talk with the bees, with the Melissa …’

Give and Take…

For to the bee, a flower is a fountain of life

And to the flower, a bee is a messenger of love

And to both, bee and flower,

the giving and the receiving is a need and an ecstasy.

Khalil Gibran

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telling_the_bees#/media/File:The_Widow_by_Charles_Napier_Hemy.jpg

“Royal beekeeper has informed the Queen’s bees that the Queen has died, and King Charles is their new boss in bizarre tradition dating back centuries”: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11199259/Royal-beekeeper-informed-Queens-bees-HM-died-King-Charles-new-boss.html

https://www.insider.com/royal-beekeeper-bees-queen-death-king-charles-old-tradition-2022-9

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45491/telling-the-bees

https://burialsandbeyond.com/2021/04/17/telling-the-bees/

https://daily.jstor.org/telling-the-bees/

Historical Honeybee Articles: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMz5pXT7uHo

“In many places there is a beautiful tradition that Bees are considered part of the family and must be informed therefore of all family deaths and special events. Superstition tells us; if their master dies, they must be told and put into mourning, for if this is not done, they will pine away and die, or abandon their hives and fly away. The formula for telling the bees varies little from place to place; A family member walks sombrely to the bees, with becoming reverence and sorrow a piece of black crape is draped over the hives to put the Bees in mourning, -for the bees are supposed to have sorrow upon sorrow on account of the death of their master. Like their masters’ friends and relations, they must, as they do, wear the signs of mourning. The informant informs the bees by tapping three times on each hive with the house key and says; “Bees, Bees, Bees, your master is dead,” He then says; “your new master is ________.” Superstition holds that it is bad luck to purchase Bees of a dead man, so the Bees are always given to their new master.”

http://www.thebeegoddess.com/id40.html

See also: Morgana- Tales from Anatolia, Hekatesia 2005:

https://wiccanrede.org/2012/07/tales-from-anatolia-hekatesia-2005/

https://womenandmyth.org/2008/10/28/the-bee-goddess-and-aswm/

Golden Labrys: https://thegoddesshouse.blogspot.com/2011/02/sacred-symbols-of-goddess-labrys.htmlml#

Labrys seal ring: https://feminismandreligion.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/labrys-seal-ring.jpg

Bees and Toxic Honeys as pointers to Psychoactive and other Medicinal Plants: ““Tradition holds the famous Delphic Oracle ..”: https://ibogaine.mindvox.com/articles/delphic-bee-jonathan-ott/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melissa

For more information about the Labrys see my article “From Lagina to Labranda – part 3”:

Tales of Anatolia: From Lagina to Labranda, Part 3 – January 2014

Andrew Gough:

THE BEE: PART 1 – BEEDAZZLED: https://andrewgough.co.uk/articles_bee1/

THE BEE: PART 2 – BEEWILDERED: https://andrewgough.co.uk/articles_bee2/

THE BEE: PART 3 – BEEGOTTEN: https://andrewgough.co.uk/articles_bee3/

http://www.spiritual-quotes-to-live-by.com/kahlil-gibran-quotes.html