In April 2019 I was in Santiago de Compostela for a conference, and it just so happened that it was during ‘Holy Week/ Semana Santa’ leading up to Easter.

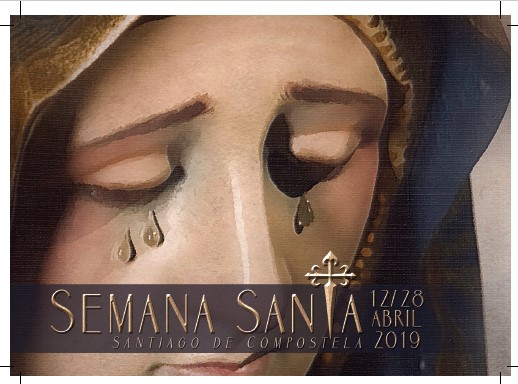

One of the first things I noticed in several shops was a strange, kind of Ku Klux Klan model. I also saw a couple of folders – in Spanish, of course, with photos of processions with people with these same high pointed hats bearing huge floats looking decidedly Christian. The folder was announcing the ‘Semana Santa’ events including the dates and times of the processions. My curiosity was aroused so I looked for more information and made a note in my diary… (See folder below) I also wanted to find out more about the people involved. And of course if there were any pagan elements.

I found out that the bearers are called Cofradias. I would later see groups carrying their own banners, including the town they came from:

“One of the many Brotherhoods that take part in the Easter Week in Santiago de Compostela is the Brotherhood of the Vera Cruz (The True Cross). Their existence goes back to the year 1548 when it was founded in the convent of San Francisco to commemorate the institution of the eucharist by means of a procession featuring the float of The Last Supper.”

I also found an excellent article describing the Cofradia:

“What is a Cofradia?

The Term Cofradía – pronounced in three syllables co·fra·día – emphasis falls on the last syllable – stems from Old Spanish confrade, from con — from Latin com = with — + frade = brother, monk, priest, from the Latin word fratr, frater, which can be translated into English as Cofraternity – Fraternity.

What are Religious Cofradías in Spain? A religious Cofradía is a fraternity of laypersons, both men and women, young and old, who have come together for the purpose of promoting special, church-approved, deeds of Christian charity or piety in the community. Cofradia members have not taken the vows of any religious order, but they conform to rules laid out by the Church.

The Link between Charitable Acts and Eternal Reward In many parts of Spain, religious devotion and daily worship in the Catholic Church were at the centre of daily life. Cofradías, or religious charitable organizations, developed during the 16th Century as members strove to find deeper meaning in their religious devotion and to ensure suitable rewards in the afterlife. The importance of charitable works that helped the poor was felt so strongly by some members of the cofradias that they made bequests to certain charities in their wills, leaving items such as bedding, clothing, or monetary gifts.

One of the First Institutions Created by Members of the Public Many cofradias, had a positive religious, social, and economic impact on society. They were one of the few institutions formed by the public to meet the needs of the public. Even though each cofradia had its own set of rules or by-laws which every member promised to live by, they worked in harmony with the Church.

In the late middle ages, Popes would grant permission for the creation of cofradias and would grant members rewards such as physical protection, eternal membership in the Cofradías both in life and in death, along with access to indulgences and forgiveness of sins.

“He who gives charity, extinguishes hunger and covers nakedness, extinguishes his own faults and covers his own sins.” ( Friar Tomas Trujillo )

Cofradias Cradle of the Arts. Originally, the Cofradias were advocacies of supporting strong professional institutions. Thus, for example, in medieval Europe, the creation, legislation, and regulation of theatrical performances depended on Cofradias, some of which were created by kings or bishops. Among the best known and most important were the “Cofrères de la Passion” in Paris or the “Disciplinados de Jesus Cristo”, in Umbria. Other examples are the brotherhoods of Dutch or guild painters, and the Spanish theatrical la Cofradía de la Pasíon y Solitud (brotherhood of The Passion and Solitude) as well as the 17th Century Brotherhood in Madrid, Los Escalabos del Sacramento Bendecido (Slaves of the Blessed Sacrament), whose members included highly talented poets, playwrights, and writers.

Cofradías Today Cofradias still work and are created in the same way and with the same criteria as they were from the beginning. There are about three million Cofrade members in approximately 10,000 brotherhoods throughout Spain today. One of their key roles is the preparation of the Easter Festival, a religious event that is currently going through its “silver age” although within the framework of a “secularized” society in which processions become a way to bring the Church closer to the people. Most brotherhoods organize a procession, at least once a year, either alone or together with other brotherhoods.”

On reading the above I was reminded of the Freemasons and the charitable work done by them. Freemasons are also renowned for their regalia. The Cofradias wear a hood, often a tall pointy one, which is called a capirote, and are used during the Semana Santa’s celebrations. “Traditionally, capirotes were used during the times of the Spanish Inquisition: as a punishment, people condemned by the Tribunal were obliged to wear a yellow robe – saco bendito, aka blessed robe – that covered their chest and back. They also had to wear a paper-made cone on their heads with different signs on it, alluding to the type of crime they had committed.

Centuries later, cofrades (people affiliated to Catholic brotherhoods) and nazarenos (hooded penitents) started to use them during Easter processions to symbolize their status as penitents. Today, the capirote still indicates the penitent’s attempt, through penance, to get closer to God; it also covers the person’s face, in order to mask their identity.”

The hooded penitents are found participating in ‘Semana Santa’ in many parts of Spain including Granada, Madrid, Palencia, Cartagena and Seville.

I am also reminded of some of the celebrations throughout Europe where costumes including pointy hats are included. The fool, the harlequin, for example…but this is all for a different article. NB the Dunce’s Hat – a white pointy hat has a totally different origin.

In any event, the Cofradias and the processions, as such, don’t seem to have any pagan connections. But perhaps our Spanish readers have other insights?

I managed to take some photos and video’s of the processions in April 2019. Enjoy!

References:

Program Semana Santa folder April 2019. In Spanish.

Programa Semana_Santa_ Holy week_april 2019Easter week Santiago de Compostela: https://www.magichillholidays.com/easter-week-santiago/

What is a Cofradia?: https://northernspaintravel.com/what-is-a-cofradia/

Why Spain’s Easter white hoods are a symbol of penance, not of right-wing extremism: https://www.thelocal.es/20190408/capirotes-are-a-symbol-of-penance-not-of-right-wing-extremism/

Video’s