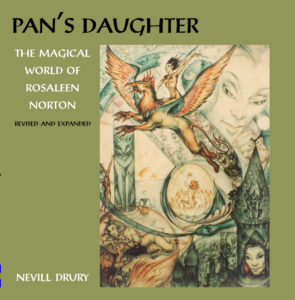

Pan’s Daughter – The Magical World of Rosaleen Norton

Revised & Greatly Expanded Edition; Nevill Drury

Mandrake of Oxford (UK); 2nd ed. Edition (24 Jan. 2017)

Format: Softcover/326 pp/48 illustrations. ISBN: 978-1-906958-41-1.

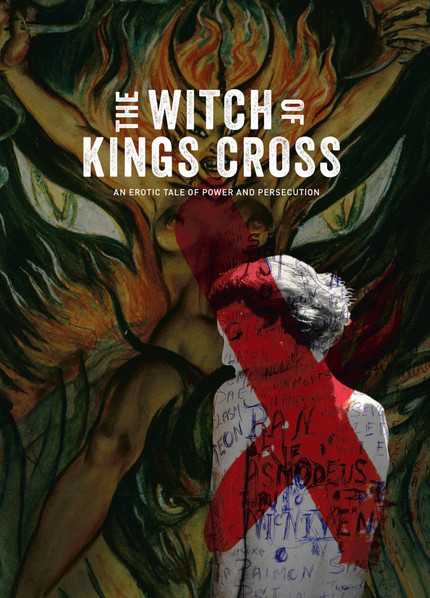

This review has been sparked by the recent launch of the documentary “The Witch of King’s Cross – The Soul of a Great Artist Laid Bare”.

The Witch of Kings Cross – Teaser 90 sec Premiered on 24 October 2020

“Australian filmmaker Sonia Bible tells the remarkable story of a gifted painter and artist, and daring woman, one who shocked the public in the mid-20th century, yet refused to compromise her life or her work.”

Pan’s Daughter is the only biography of Rosaleen Norton and provides the most detailed and authoritative account of her magical beliefs and practices. First published in Britain by Mandrake in 1993, and now it is reissued in a revised and expanded edition.

I remember hearing about Rosaleen Norton many years ago when we first had contact with pagans and witches in Australia in the mid 1990’s. Her name would also come up in conversations about the British occult artist Austin Osman Spare with whom she was compared. Their paintings often depicted images of demons, supernatural entities and pagan gods.

It was her book The Art of Rosaleen Norton (1952) which caused a huge controversy in the conservative, puritanical, Christian Australia of the 1950’s.

The 1952 edition was soon banned from importation into the USA on the grounds of obscenity and also had a restricted circulation in Australia, with a court ruling that some of the plates had to be ‘blacked out’ before copies could legally be sold. It was reprinted in Sydney in 1982, but with a number of changes and omissions. This Teitan Press edition is the first US publication of the book, and the first reprint to include a complete facsimile of the original 1952 edition.

(She apparently sent a copy of her book to Gerald Gardner)

From her early childhood Rosaleen would shock people with her drawings. Expelled from a CoE / Church of England Girl’s school at 14 for ‘her eccentric and disruptive behaviour’ she would continue to shock throughout her life.

Her connection with the God Pan and the way she perceived Pan as the source of all life has influenced many neo-pagans and witches. In this book there are a number of black-and-white drawings which provide a glimpse into her world.

A fascinating woman … and a fascinating book.

In this biography Nevill Drury who met her in 1977 describes this encounter.

Dr Nevill Drury on Rosaleen Norton

I met Roie towards the end of her life, in 1977. She had already become a recluse but a friend of mine, Barry Salkilld, and I had tracked down a person called Danny who knew her. Danny worked in a jeweller’s shop in Kings Cross and we explained to him that we were genuinely interested in magical techniques and practices and wanted to discuss both her personal view of magic and her perceptions of the world at large. The message filtered through and we were granted an interview.

Roie was living then in a rather dark basement flat at the end of a long corridor in an old building in Roslyn Gardens, just down from the Cross in the direction of Rushcutters Bay. She was somewhat frail but still extremely mentally alert, with expressive eyes and a hearty laugh. She even invited us to share an LSD trip with her, but in the gloomy recesses of her basement flat we shuddered to think of the shadowy beings we might unleash through this powerful psychedelic, and we both politely declined. I later found out that Roie periodically used LSD to induce visionary states and that this was all about enhancing her awareness as an artist. She did not, however, use the drug simply for recreation, for she was well aware of its potency.

We talked at that meeting about the gods Roie encountered in trance, about her view that Pan was alive in the ‘back-to-Nature’ movement supported by the counterculture, and we also discussed her strong personal bond with animals. Roie told us that she believed most animals had much more integrity than human beings and she also felt that cats, especially, could operate both in the world of normal waking consciousness and in the inner psychic world simultaneously. She even remembered a time which may have been a previous incarnation. She believed she had once lived in a past century in a rickety wooden house in a field of yellow grass, somewhere near Beachy Head in Sussex. There were several farm animals there – cows, horses and so on – and she herself was a poltergeist, a disembodied spirit. She recalled then when ‘normal’ people came near the house they were frightened by her presence and could not accept the existence of poltergeists or any other ‘supernatural’ beings. But the animals accepted her as she was – as part of the natural order.

For Roie this went some way towards explaining her love for her own pet animals, and throughout her life, she lived surrounded by creatures of all kinds – from pet lizards and spiders through to mice, turtles and cats. In the Cross, in her dark and very private living room, she still had her animal friends to comfort her, and she related to them more positively than to her human neighbours in the daylight world outside. One couldn’t help feeling that here in the twilight realm of her Kings Cross basement flat she felt thoroughly at home. She no longer felt any strong desire for regular contact with the external world.

This book is not only about the life and times of Rosaleen Norton, but also describes her rather complex and unusual world view. Her personal beliefs were a strange mix of magic, mythology and fantasy, but derived substantially from mystical experiences which, for her, were completely real. She was no theoretician. Part of her disdain for the public at large, I believe, derived from the fact that she felt she had access to a wondrous visionary universe – while most people lived lives that were narrow, bigoted, and based on fear. Roie was very much an adventurer – a free spirit – and she liked to fly through the worlds opened to her by her imagination.

Roie’s art reflected this. It was her main passion, her main reason for living. She had no career ambitions other than to reflect on the forces within her essential being, and to manifest these psychic and magical energies in the only way she knew how. As Roie’s sister Cecily later told me, art was the very centre of her life, and Roie took great pride in the brief recognition she received when the English critic and landscape artist John Sackville-West described her in 1970 as one of Australia’s finest artists, alongside Norman Lindsay. It was praise from an unexpected quarter, and it heartened Roie considerably because she felt that at last someone had understood her art and had responded to it positively. All too often her critics had responded only to her outer veneer – the bizarre and often distorted persona created by the media – and this was not the ‘real’ Roie at all.

I hope that this book throws some light on her extraordinary life, for we have not seen anyone else quite like her since her death in 1979. She was an amazing person – a woman of strong convictions and unusual beliefs – and quite a deal more complex than the cheap, sensationalistic stories in the tabloids would suggest. As will become obvious, Rosaleen Norton was very much ahead of her time and was widely misunderstood by the public at large. I sincerely hope that this book will go some small way to correcting these lingering misconceptions.

Nevill Drury – Pan’s Daughter (Hardback edition 2013) pp 13-17

(Reprinted with permission.)