In my last essay I criticised styles of thinking that led many Pagans to attack other Pagans in the name of their having committed ‘cultural appropriation’. Supposedly, EuroPagans using smudge sticks or Day of the Dead decorations were ‘stealing’ what belonged to another culture. These critics’ mistake, I wrote, was in treating a ‘culture’ as a kind of thing, and different cultures were different kinds of things, all requiring respect from those on the outside. Further, they often argue only certain people in a culture are truly qualified to teach these customs to outsiders. Some people are ‘better’ representatives than others of what a culture supposedly is, which is about as authoritarian and essentialist a position as it is possible to take.

Their error was in using an organismic model to describe an ecosystem. In reality, a culture is its entire pattern of relationships, and a meme/thoughtform of any part of a culture could be incorporated into another, or disappear from the one in which it is important, without necessarily harming anyone or making the culture into another one. I used the example of how marriage for love transformed marriage and ultimately much else, in the West, which still remained a distinctly Western culture.

Within the Pagan community there is another dimension to this error, found on the NeoPagan right wing.

The NeoPagan left and right share a common insight in rejecting traditional forms of reductive individualism as incapable of grasping the importance of culture. They also share a common error in treating culture as a thing or an organism, though they interpret the implications differently. Those on the right regard their culture as threatened by ‘weaker’ or ‘inferior’ cultures whereas those on the ‘left’ regard the ‘weaker’ as threatened by the ‘stronger’. Both emphasise separateness and cultural purity. Right wing völkisch thought more explicitly treats cultures as entities superior to their human parts, who can be better or worse representatives of it, depending on how well they embody its ‘essence’. Exploring these views enables us to probe still more deeply.

Rationalistic currents within the Enlightenment emphasised all people were the same, and its increasingly secular view of the world treated all of the earth as resources for human use. This view became increasingly dominant as industrial economies increasingly replaced agriculture as the source of employment and prosperity. It is no accident that much of modern economic theory claims to be the ultimate foundation of the sciences of society, for it conceptualises us and our world as ‘labour’, ‘land’ and ‘capital’, and then seeks to unpack its meaning. The saying “economists know the price of everything and the value of nothing” captures their error.

As relations between human beings as well as between human beings and the land were increasingly defined by money relations, values that could only poorly be expressed in these terms were increasingly devalued by mentalities rooted in instrumental calculation. In reality, rural communities did not simply exist to produce food. They also consisted of complex relations and values that gave their inhabitants meaning and pride in their lives, including shared histories and intertwined lives. When these communities declined, the issue was not just that a ‘better’ way was found to produce food. Even with all their flaws, ways of life which also gave meaning to their members also withered. These problems could not be understood in terms of ‘land,’ ‘labour,’ and ‘capital’.

These threatened ways of life and the values expressed by them were also connected to the landscape within which their members lived, a point repeatedly emphasised by völkisch writers.

Land and psyche

I grew up in Kansas, an American state far removed from mountains, substantial hills, or large bodies of water.

When I am on the West coast I feel hemmed in, much as I love it. I can go East, North, or South, but the West is closed to me. And California’s skies are usually boring. When in the mountains, my favourite place is high up, where the horizon is no longer hemmed in by surrounding peaks. The skies are far more interesting than on the coast, but the storms are junior sized compared to the towering clouds of a mid-western thunderstorm. As my father often said, in Kansas the scenery began at the horizon and moved up.

By contrast, many of my West coast friends have told me they feel trapped when they are far from the ocean. Some are as terrified of tornadoes as I was of earthquakes when I first moved to California. The endless horizon of salt water gives them a sense of freedom they miss when far inland.

I am not describing beauty. The coasts and mountains are often beautiful beyond anything I could have imagined before seeing them, and people from the coasts find the mountains, (and sometimes even the Kansas plains), beautiful. Rather I am describing feeling at home, closer to loving the inner soul rather than loving a beautiful sight.

Pretty clearly, the landscape around us can shape our psychological proclivities. The questions are, how deep, and why? The modern world generally answers the first question as “not very” and the second as “personal taste”, akin to whether we like chocolate more than a peach. An animist Pagan view, such as mine, and as implied in many traditional Pagan practices, answers both questions differently: very deep and due to the fields of energy, or the Presence, within which we live. This is where such a Pagan outlook clashes most profoundly with secular modern thinking of all ideological flavors, left, centrist, or right alike.

Subtle energies

Understanding memes as thought-forms, which I discussed in my last essay, opens us to a deeper understanding. As thought-forms, memes exist in a mental or psychic dimension of reality distinct from what we regard as physical reality. This is a dimension we experience directly whenever we cast a circle, raise energy for a healing, or engage in some similar working. Anyone who has done such work knows that a focused attention can shape energy and imbue it with a purpose.

Further, this psychic dimension with which we interact is not locked up inside our heads, but exists in some way within our environment. We live, and have always lived, within not only a physical environment, as that term is usually employed. We also live immersed within a more subtle energetic environment which interacts with our minds. Influence runs both ways.

Most of us can learn to see and feel some forms of this energy. For many years I taught workshops on working with this energy, including learning how to see and feel it. I have written how to do this here. If you can’t see or feel energy, and want to, take a look at this site. If you already can, or are just willing to provisionally grant me this as true, let’s continue…

Trees and other plants possess these energetic fields as well, although they are different in some ways from ours. If you can see at least the densest of these fields around a person, use the same technique and you will see it around trees. It is easiest when the background is simple so fields from various plants do not interpenetrate. Best of all, in my experience, is checking out tree trunks surrounded by snow.

When we walk through a forest our fields interpenetrate with theirs, as well as with the fields of all other living things in the area and perhaps even with those of what we normally consider to be inert, like rocks. In fact, we are continually immersed in such fields.

Energy and the land

We evolved within this network of fields, and an environment where they are thin or disrupted is alien to our natural state of being. This helps explain why scientists have discovered that being out in nature is good for us physically and mentally, and apparently the more complex the environment, plant-wise, the stronger the effect. For Pagans who work with these energies this should not be surprising because much of our healing work, and that of “energy healers” in general, makes use of this energy, sometimes to amazing effect.

The quantity and quality of such energy varies. A ritual circle is best accomplished when there is no friction among its members, and a circle of experienced people is usually stronger than one of newcomers. In both cases the energy associated with people working together is more harmonious. But this diversity also applies to the other-than-human environment within which we live. Cities have different ‘feels’, as do different neighbourhoods. So do different country-sides. Sacred sites, both natural and those containing human constructions, will often have a different ‘feel’ than similar sites that have not attracted such sustained attention. Our psychic and energetic environment is as complex as the one we associate with the material world.

Because their ecosystems will consist of different mixes of organisms, different regions will have a somewhat different field of energy. I believe this is why when we are raised within a particular region, we get a kind of home-imprint that is distinct from how beautiful or comfortable it might be. (For me, Kansas is way too hot and humid in the summer to be comfortable physically. I don’t want to live there – but I feel at home there.)

A culture arises within its ideational field of energy of dominant customs and beliefs, and also the energetic fields of its natural environment. But, like an ecosystem and unlike an organism, it will reflect within itself different cultural ecologies. This is particularly true in mountainous regions where the ‘same’ cultural area will often have dialects of their language that are difficult for others to understand, as in Italy and Norway, as well as with native Spanish speakers here in northern New Mexico compared to those down in Mexico itself. Every dialect is a potential new source for a Volk if it remains isolated and distinct enough, as happened to Latin speakers after the fall of Rome.

With the loss of connection to the land, and ignorance of this energetic dimension, those seeking to distinguish cultural collectivities from one another have often been led to embrace racial or ethnic explanations without a basis in science. The Pagan right-wing is particularly prone to embracing this confusion, rooted in their misunderstanding of Darwin, genetics, and the distinction of an ecosystem from an organism. But their intuition that something vitally important is lacking in purely abstract conceptions of humanity or the isolated individual is rooted in genuine experience, however misdiagnosed.

There is something important in the insight that language and region support a Volk. But this field of relationships is an ecology, not an organism. It is open to its wider environment, and no single element is definitive in identifying it. Because of its weaving of region and cultural thought forms together language goes furthest, but language is particularly open to new influences and unexpected transformations, as the previous essay’s discussion of marriage and love indicates.

A lesson can be learned from some Indian tribes in the U.S. The Navajo nation today recognizes four sacred mountains that border its traditional territory. They are Blanca Peak (Tsisnaasjini’ – Dawn or White Shell Mountain) to the east, Mount Taylor (Tsoodzil – Blue Bead or Turquoise Mountain) to the south, the San Francisco Peaks (Doko’oosliid – Abalone Shell Mountain) to the west, and Hesperus Peak (Dibé Nitsaa – Big Mountain Sheep or Obsidian Mountain) to the north.

These mountains are deeply embedded in the Navajos’ traditional ritual life and, even though the region is economically poor, many prefer living there to anywhere else. The Navajo constitute a good example of Herder’s Volk. And yet, the Navajo’s ancestors emigrated from far to the north. The language they speak is part of the Athabaskan linguistic group, located mostly in Northern Canada and Eastern Alaska. For generations no Navajo had seen a boat, but the word used by Navajos to describe the gliding flight of an owl is identical to that used by Northern Athabascans to describe the movement of a canoe over water. Yet today’s traditional Navajo are adamant that the high plateau of the American Southwest is and always has been their home.

They are right. Not in terms of their ancestors’ origination, but in terms of who they are as a people incorporating the völkisch linguistic and natural ecology within which they dwell. Despite a genetic and linguistic past when their ancestors lived in very different realms, they are a people of this region, their minds, customs, and spiritual lives shaped by it. The Volk is an ecological cultural concept, a pattern that is neither merely the sum of the individuals within it, nor an organic whole of which individuals are parts.

When Johann Gottfried Herder first conceptualised the Volk, this concept was not available to him. But neither is it unrelated to his work. Ecology as a concept only began to take shape with the work of Alexander von Humboldt, who had been influenced by Herder. Ernst Haeckel, who coined the term “ecology” was in turn strongly influenced by Humboldt’s pioneering work, as well as Darwin. The concept of ecology enables us to grasp the Volk is not an organism but a pattern of relationships that always remain open to their environment.

This way of understanding how our physical and energetic worlds interact offers us a way of understanding the emptiness of the modern industrial world view, and the sacredness of the world of nature, without falling into the equally mistaken authoritarian and racist völkisch thinking of the Pagan right-wing.

Reinhabitation

It also offers us a way to reinhabit our place, wherever it might be. The Wheel of the Year is a map of the year’s cycle no matter where we might live, other than perhaps the tropics, which have their own traditions. But the Wheel rolls differently in different places, most obviously in the Southern hemisphere, where its cycles are the opposite of those in the Northern. The concept of the Wheel of the Year is also hardly unique to NeoPagans. Here in New Mexico, The Zia are descendants of ancestral pueblo peoples from four corners region of the United States. Traditional Zia consider four a sacred number, and their sun symbol exemplifies many aspects of this sacredness: the four points of the compass; the four seasons of the year; the four periods of the day: morning, noon, evening, and night; the four seasons of life: childhood, youth, middle years, and old age; and the four sacred obligations: cultivating a strong body, clear mind, pure spirit, and devotion to the welfare of others.

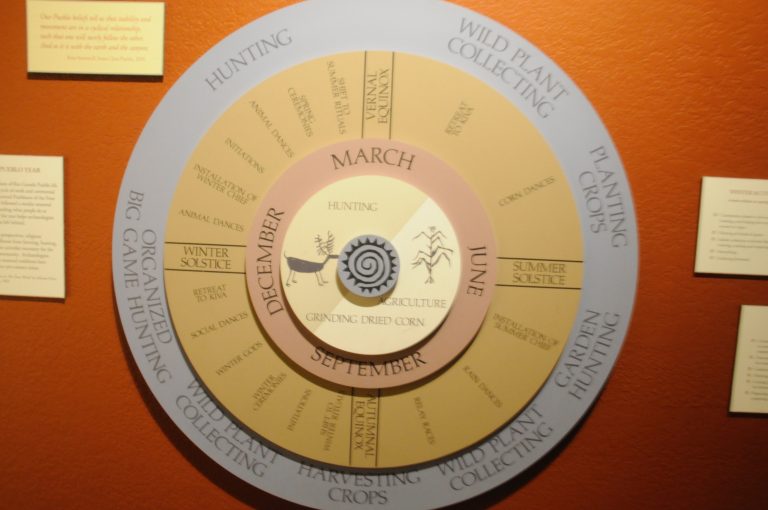

The Anasazi Heritage Center describing the pueblo peoples of this region also features a wheel of the year in its museum.

This is obviously not a traditional symbol, but it illustrates how a tribe’s ritual cycle occurred in keeping with a wheel of the year sensibility in some ways remarkably harmonious to our own way of thinking. To my mind we EuroPagans will have begun to grasp the deeper meanings of our place and its presence when we integrate it into our own Wheel of the Year symbolism as a balance between the universal cycles within which we all live, and the specific qualities of those cycles where we live.

References

Woodward Oklahoma, Photo by Lane Pearman: https://www.flickr.com/photos/fireboatks/14224758292