Interview with Georgi Mishev, author of ‘Thracian Magic: past & present’

by Kenn Payne

Fig. 1 Georgi Mishev at the Thracian sanctuary Mishkova niva in Strandzha mountain

1. What are your earliest memories of Hekate in your life?

To recording some experiences and emotions and the desire to convey them by means of language is really hard and on one hand gives the opportunity to others to get a glimpse of it, but on the other takes away from them their true feeling and thrill. When these experiences are related to contact with the divine they really are a part of the most intimate world of a person and this makes their description even more specific. Still the recorded remains and in this connection, no matter that the text containing such narratives might be just their pale reflection – it still gives the opportunity to the others to get glimpse of one such connection and to seek their own.

I have always found it difficult and unnatural to describe my experiences and my memories connected with the image of the Goddess. I hope that the readers will forgive me my inability to convey the sensations and the true intimacy of these experiences, but I’ll try to a certain extent to tell about how and why I took and stood on that path – the path of the Goddess. Unlike the numerous romantic stories about divine revelations and enlightenments in the teenage years, my first memory of a kind of interaction with the Goddess was at the age of 7, during a severe illness. [1] Of course at the time I wasn’t familiar with her namings such as Hekate, Bendis and others. For me she was a huge female silhouette, which in that burdensome moment gave me peace and strength. Probably this is the main thing that marked my perception of the Goddess. In relation to Her I will always remain in the image of that child which felt under Her protection, which is going to seek Her approval and which is going to want to earn Her benevolence. The contact with the divine is a crucial moment, which marks the whole life of a person. ‘Seeing’ the divine implies difficulties, because it separates a part of us outside the normal and the human and places it in another world, which follows its own rules and norms. Such contact in a Christian environment usually has a couple of ways for development. One of them is when a person finds comfort in the Christian ideology (or respectively in some other official religious doctrine), but there is also another path, which in its essence is heretical, because it separates from the official. I can’t tell that either the one or the other is completely true for me because the Bulgarian traditional belief is much closer to the ancient pagan notions, than to the Christian canon. Some would call this syncretism, but this syncretism has more pagan than Christian elements. I grew up in a folk environment filled with dreams in which female ‘saints’ (in my opinion the Goddess) give behests and directions for performing rites – preparing of sacrificial breads, washing with herbs and others. This folk environment, as well as the deep connection with nature (for which I am especially grateful to all those elderly people, which surrounded me in my childhood), have defined in a great scale my perception of the Divine. The elderly healers in my native region, as well as the other people their age, had their own opinion and perception of the Divine, which was completely different from the official Christian view. Some years ago when I was drawing an icon of a female saint worshiped in my hometown, I depicted her not in the manner of the Christian canon, but like she was dreamt by a local woman. The words of that woman were: “Here we see her like that, we dream her like that…” My introduction to the magical rituality also took place in this environment. There were no books, no grimoires and no pretentious explanations about the energies. Folk magic is a carrier of the folk wisdom and those who practice it are unusual people. Their strong will is their main instrument, which armed with the knowledge of generations of ancestors, who inhabited these lands, makes them exceptional persons. The thing that’s different when someone is initiated in the magical in a traditional way and as a part of the traditional folk culture is exactly the recognition of authority. In the rituality there is no equality. Individuality is an important element of folk magic, when it transforms in part of the line of generations; in that case it complements and enriches them or vice versa. Along with the recognition of authority, what one learns is responsibility. The rites performed in a small collective suppose taking responsibility for their consequences. This is different from the contemporary environment where often the so called magicians and their patients/clients don’t know each other or never meet each other again. Motivation is the next major milestone. The elderly healers always used to say that assistance should not be refused and money should not be demanded, i.e. the motivation should never be connected with one’s own economic well-being. The image of the Goddess is preserved in the folk rites and although She is called a saint, in the rite She always remains the Great Goddess. The ritual texts of the incantations, the calendar rituals and the beliefs preserve until the present day an image of a divinity which combines all the elements, because they descend from Her. But of course with time, the one who has had some kind of contact with the Goddess, begins to understand that what he or she felt differs from the official religious doctrine (in my case the Christian), where the image of the Goddess is degraded and even humiliated.

2. What was the first book you read on Hekate?

I can’t say with certainty which was the first book I read in this connection, because this was really a long time ago (before 16-17 years).

Fig. 2 Georgi Mishev and Ekaterina Ilieva, translator ‘Thracian Magic: past & present’ at the Thracian sanctuary Harman kaya in the Eastern Rhodopes

3. How has your worship of the Goddess evolved over time?

The seeking, the studying of historical sources, as well as the connection between the places of performing a number of rites and the ancient sanctuaries situated there, determined also the development of my perception of the Goddess. In this moment of realization begins and the separation in one completely formal way, as it happened with me and with the formation of Thracian society ‘Threskeia’. The human is of course a social animal and seeks people with similar beliefs and perceptions. This is how our group formed, which we called ‘Threskeia’. The very word has Greek origin and it was used by the ancient authors to name the rites, which the Thracians performed, as well as their more different religious notion. Self-naming gives distinctness, recognition, which is an important moment in the world today. Of course we don’t seek the return of the past, but in the same time we don’t share a number of the beliefs of the contemporary pagans and wiccans in the sense that everything is permitted if it doesn’t hurt anyone. The conservative nature of our group, as well as the strict ritual discipline and rituality are based on many things. Most of us are very familiar with the traditional belief, i.e. follow rites established by generations before us. We know well and perform our rituals on many of the ancient sanctuaries. The ancient sacred places require respect and following certain rules of behaviour. This is of course really hard to understand by some contemporary pagans, which have formed their views on the basis of the books they have read and the movie productions they have seen. In this sense we don’t deny the personal contact of each of us with the divine, their enrichment and personal development, but in the same time we don’t think that the individual must shape millennial cultural messages. That is why the spiritual path of the group rite is the same in deed and words, but in its individual performance and application is a personal responsibility and right to every carrier of the belief.

Fig. 3 Georgi Mishev and priestesses of Threskeia at a crossroad honouring the Great Goddess

4. Can you share some insight on how you and your fellow worshippers view the Goddess and worship her in your homeland?

We worship and see the Goddess mainly as a Creatrix and Womb of life. Because she is the beginning and in the same time contains the end and what is between them. The calendar period and the nature itself are images of the different manifestations of the Goddess. Along with that during each and every day She also appears and receives honour in her many forms. The main thing is that She is unity in multitude. Although we have sacred images, we almost don’t use them in our rites, because within an ancient rock sanctuary we perform the rite in the embrace of the Goddess. Sometimes the ancient Thracians call the Goddess – Mountain Mother and probably that’s the reason why most of the rites done in Her honour even nowadays are done on high places in the mountains, near sacred springs or in the womb-like darkness of the caves. For thousands of years the Thracian culture has assimilated the space, sacralised it and this is inherited until today in the Bulgarian traditional culture. In the rituality itself most of the ritual elements are also traditional – the ritual breads, which are prepared by the women (offered by the priestesses), the wine poured by the men in a toast (by the priests), burning frankincense and so on. In this sense the Hittite ritual texts are very helpful and beneficial because Thracians and Hittites are very close both ethnically and culturally, i.e. and in religious plan. If the Thracians didn’t leave us writings about their rites, the Hittite have done it in full detail. Even if they are not identical, they have a lot of parallels in the traditional rituality, which is preserved even today.

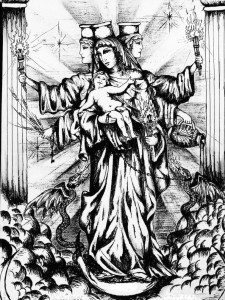

Fig. 4 Hekate Kourotrophos (nursing the children) by Georgi Mishev

5. You are also a talented artist; can you describe how you work through the creative process in relation to your faith and worship?

I draw from an early age, but depicting the Goddess and other divinities has always been one more special process. Usually the image is a vague shape in my mind and during its creation it clarifies and forms, sometimes different than my original vision. The creation of an image for a certain person or for a certain reason is very interesting, because I have the feeling that a special bond is created between them and they affect each other. No matter how much authorship and creativity I invest in the images of the Goddess, I think that the tradition should be followed. The attributes of the divinities, the way of their depiction, shaping their accessories, all this is connected also with ritual acts. This is what distinguishes the cult image from the plain picture or sculpture. Following the tradition the newly created image also fits in one spiritual path and bears a spiritual message. Of course there are always innovations, but the cultural symbols are such exactly because they have become a layer of our collective memory, but not of the whims of individuals. This is how the way things are, in my opinion, in the sphere of rite and faith, the art for art’s sake is another topic. When we want to send a letter we take into consideration the postcode and the address of the addressee; and how pretty we’ll write the numbers and what envelope we’ll place the letter is an addition, but not the essential. But if we write instead of the prescribed postcode our favourite numbers or just some sequence of numbers, which we like, it is quite possible that the letter will be received, but not from the one we think we are looking for…

Fig. 5 Mother of the Sun by Georgi Mishev

6. What inspired you to begin writing your book, ‘Thracian Magic: past & present’ and how long did it take you to write it?

Actually the idea for writing the book ‘Thracian magic: past & present’ came really spontaneous during a conversation with Sorita d’Este. While we were discussing different topics and the drifting of the contemporary pagans away from the traditional practices and beliefs, she asked me why I don’t write a book, which will introduce and give the opportunity to more people, i.e. the English speaking readers, to become familiar with Bulgarian folk belief, rites and magica. The Western world in a great scale underestimates this part of Europe, the Balkans. Of course this is most often due to the economic criteria, but on the other hand this part of Europe, where in antiquity flourished the cultures of Thracians, Illyrians, Hellenes and others, has preserved a lot of relicts from the past. The unique destiny of Bulgaria is the reason why in the Bulgarian traditional belief are preserved, until a very late stage, many pre-Christian beliefs and rituals. The huge quantity of the material, which I wanted to include in the book was the reason why writing it took me two years. The text, which was published, is actually probably one third of the original contents, which I was planning to develop. I hope, if the Fate is favourable that the other two parts will also see the light of the day.

7. What was the hardest part of writing your book?

Without doubt the hardest part was to sift out the things – what will be and what won’t be in the book. On one hand this has to do with rites and on the other about the information of those rites. Every book is a message and a way of communication. The oral transmission of knowledge begins to fade in the past and though it can never be completely displaced by the written, the book becomes an increasingly important part and greater opportunity for preserving the cultural memory. The rites are for the people, they are a chance for communication with the divine and development of the divine, which is in us. The contemporary world is oversaturated with modernistic, futuristic and pretentious practices, which instead of giving us back our connection with nature do exactly the opposite. It is not the same to meditate for a walk in the woods under the full moon and to really do it; when are we going to stop fearing the world around us? The most difficult part of the book was namely this – to explain to all these people, who make the rituals and the rites, that they bear responsibility before the Gods, as well as before their ancestors, and mostly before what Socrates calls – their personal daemon, i.e. their consciousness.

8. Did you learn anything from writing your book and what was it?

The process of writing a book is beneficial also to the author or at least it was for me. When you explain something, you put in order your own thoughts. During the research new and unknown facts, which support, expand or change the thesis of the author, always arise. What makes me happy and what I’m proud of is that writing ‘Thracian magic: past & present’ was the reason to meet many people, visit many places and experience a lot of emotions. I can say absolutely earnestly that I hope that the reader can sense the difference, when the author has really visited, saw and experienced the things he is writing about. The caves, springs, rites and people in this case are not reported information, which has been gathered around the libraries, but they are living places, events and people, which I hope I managed to bring closer to you – the respectable readers. In this connection I would like to thank you as an author, my dear readers, for this that with peeking in my book you have decided to be part of the magical spirit of antiquity, which still lives on in the lands of Southeastern Europe and resp. Bulgaria.

[1] The story is told in detail in ‘Hekate: Her Sacred Fires’, ed. by Sorita d’Este, London 2010, pp. 67-71