Eind april is het in Nederland al decennialang Koninginnedag/Koningsdag, en op 6 mei wordt de nieuwe vorst gekroond in het Verenigd Koninkrijk. Een mooie gelegenheid om eens uit te zoeken hoe het ook alweer zit met paganisme en koningschap.

Waar krijgt de koning zijn macht vandaan?

Ooit las ik in The Western Way (deel 1) van John en Caitlín Matthews over ‘sovereignty’, soevereiniteit. Maar dat dan niet zozeer in de betekenis van ‘hoogste macht’ of oppergezag, maar eerder in de betekenis van Lady Sovereignty. Dat is, zeg maar, de dame die het land of volk vertegenwoordigt, en aan wie de koning zijn autoriteit ontleent, of van wie hij zijn macht verkrijgt. Op voorwaarden, want het contract tussen land en vorst vraagt van de koning dat hij het land dient. Een vorst zit niet op zijn troon voor eigen gewin, maar vanuit een opdracht. Voordat de titel overerfbaar werd, koos het volk de beste persoon voor die verantwoordelijke taak. En omdat er nogal eens fysieke kracht nodig was – op het slagveld waar de koning de troepen aanvoerde – wilde je liefst een fitte koning. Na een aantal jaren werd die dan vervangen door een vers exemplaar, ook als de vorige niet sneuvelde in een oorlog. Dient een koning zijn land niet, dan kan hij natuurlijk ook van de troon worden gestoten. Je pleegt niet ongestraft contractbreuk.

Ik haal het boek1 er even bij, want het is me al lang ontschoten over welke periode dit ging, en of ik het wel goed onthouden heb. Het hoofdstuk gaat over ‘Rite and foretime’, rite/ritus en ‘vroeger’ dus, de periode van ’tribal rituals’ ofwel stammenrituelen. Clans. Maar uit die tijd hebben we (de Britten met name) nog altijd seizoensrituelen overgehouden, en kroningsrituelen. Clanrituelen zorgen voor verbinding tijdens grote ceremonies met de hele stam, en een Schots stamhoofd vertelt over de verplichtingen die zij en haar clan hebben ten opzichte van elkaar, een verbond dat berg noch zee kan verbreken – de spirituele ban van clanlidmaatschap omvat hen allen.

And however blasé we may be about our own national cohesion, the coronation of a monarch is still an event surrounded by numinous awe, bridging the ages with its pageantry, the exhibition of heraldic totems, the exchange of promises, and the rituals which marry the sovereign to the land – in the case of the English monarch, with the Wedding Ring of England – a potent and ancient ritual2. The inauguration of a president, although a diminished form of the royal ritual, shares the status of a great tribal event: in some parts of the world the rivalry and competition for the honour is analogous to that of the Foretime when rival chieftains fought each other in deeds of arms for the privilege of becoming tribal leader.

En hier komt het meest paganistische:

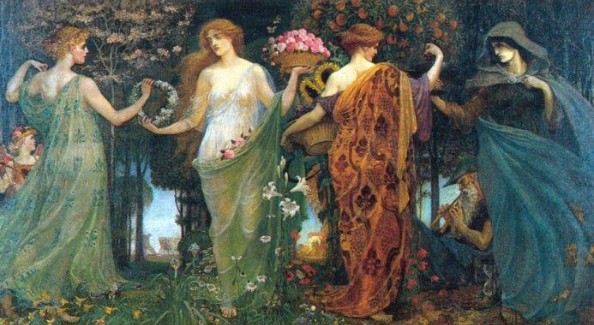

In the modern coronation rite many early practices are enshrined, but this marriage to the land is the most fundamentally important. The tribe had its being from the earth which bore it; the king, as chief representative of the tribe, had therefore to have a closer link with the earth energies. We have said how the first formulations of deity began; in many parts of the West the genius loci became personified as the Sovereignty of the land, seen as a royal queen of great bounty who either symbolically, or in the person of the shamanka, was married to the king. She was the mother of the people, and the king was her consort-steward. He administered the land in her gift and by her right3.

But while the king aged, Sovereignty did not; if his vigour did not equal hers, the king was replaced, often undergoing voluntary death to become an ancestral guardian4. …

Er volgt nog een stukje over dat de koning niet verminkt of bezoedeld mag zijn (denk aan de ‘wounded king’) en iets over de van Schotland gestolen ‘Stone of Scone’, de voorouderlijke inauguratiesteen van de koningen van Schotland.

Kroningsritueel

We blijven voorlopig bij de Engelse koning, want in Nederland kennen we geen kroning. “In het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden wordt een nieuwe Koning niet gekroond maar beëdigd en ingehuldigd. De nieuwe Koning is in functie vanaf het moment dat zijn voorganger overlijdt of troonsafstand doet. Volgens de Grondwet moet de Koning zo snel mogelijk daarna worden beëdigd en ingehuldigd.5“. De verklaring zou zijn dat een kroning religieus van aard is en een inhuldiging seculier van karakter. En Nederland houdt scheiding van kerk en staat aan.

Ook in het Verenigd Koninkrijk was Charles koning vanaf het moment dat zijn moeder, koningin Elizabeth II, overleed. Hij was troonopvolger (‘Prince of Wales’) sinds 1969, en was 73 toen hij koning werd. In Engeland is wel een ceremoniële en traditionele kroning. Die zal plaatsvinden op zaterdag 6 mei, in Westminster Abbey in London. King Charles III wordt gekroond, en Camilla wordt ’the Queen Consort’. De BBC geeft heel veel informatie over de plannen, met de codenaam Operation Golden Orb, en over de achtergronden van de traditionele elementen van de kroning. De Britse kroningsceremonie bestaat al duizend jaar en is de enige kroning met de ‘regalia’ die nog bestaat in Europa. De plechtigheid formaliseert de vorst als hoofd van de Church of England en markeert de overdracht van titel en macht.

De kroonjuwelen van het VK. Bron: Wikipedia

De kroningsceremonie kent vijf fasen:

1. De erkenning. Staande naast de 700 jaar oude kroningszetel wordt de vorst aan de aanwezigen voorgesteld, een traditie die dateert uit Angelsaksische tijden. De aartsbisschop verkondigt dat Charles de ‘onbetwijfelde koning’ is waarna hij de aanwezigen vraagt om hun eerbied en dienstbaarheid te betonen. De mensen roepen ‘God save the king!’ en er klinken trompetten.

2. De eed. De vorst zweert, met de hand op de bijbel, dat hij de wet en de Engelse kerk (Church of England) zal handhaven/verdedigen. Koning Charles kan hier wat woorden toevoegen over de verschillende geloven in Engeland. Hij heeft als prins al eens openlijk verklaard liever dan als ‘Defender of The Faith’, ‘Verdediger van het geloof’, bekend te staan als ‘Defender of the Faiths’, ‘Verdediger van geloven’ (meervoud).

3. De inzalving. De staatsiemantel van de koning wordt verwijderd en hij zit in de kroningszetel. Een gouden doek voor de zetel verbergt de koning tijdens dit meest heilige onderdeel van de dienst. De aartsbisschop van Canterbury oliet (met olie die hij uit de ampulla, een gouden fles, op de kroningslepel heeft geschonken), in kruisvorm, hoofd, borst en handen van de koning met een heilige olie naar geheim recept (maar het bevat ambergris, sinaasappelbloesem, rozen, jasmijn en kaneel, weten we. De olie die voor Charles wordt samengesteld, bevat geen dierlijke ingrediënten).

4. De kroning. Aan de vorst worden de regalia gepresenteerd: de rijksappel, die het religieuze en morele gezag vertegenwoordigt; de scepter, die de macht verbeeldt; de ‘Sovereign’s Sceptre’, een staf van goud en emaille met een witte duif als top, een symbool van rechtvaardigheid en genade. Tenslotte plaatst de aartbisschop de Sint Edwardskroon op het hoofd van de koning, het enige moment van zijn leven dat de koning daadwerkelijk de kroon draagt.

5. De installatie en eerbetoon. De koning verlaat de kroningszetel en neemt plaats op de troon (misschien wordt hij daar door de aartsbisschop, bisschoppen en edelen in getild). Traditioneel wordt hem nu eer betoond door een hele stoet van vorsten en edelen die voor hem knielen en hun trouw zweren en zijn hand kussen. In dit geval zal waarschijnlijk alleen prins William dit doen.

Als ook de koningin is geolied en gekroond, gaan beiden waarschijnlijk naar de Sint Edwardskapel, waar Charles de Sint Edwardskroon afdoet en de ‘Imperial State Crown’ op zet. Ze voegen zich bij de processie de kerk uit, terwijl het volkslied wordt gespeeld.

De kroningszetel, ook bekend als Sint Edward’s zetel of Koning Edwards stoel, zou het oudste meubelstuk in het Verenigd Koninkrijk zijn dat nog altijd wordt gebruikt voor zijn oorspronkelijke doel. 26 vorsten zijn erin gekroond. De zetel was oorspronkelijk gemaakt in opdracht van de Engelse koning Edward I, om de ‘Stone of Destiny’ te omvatten die was gestolen in de buurt van Scone in Scotland. De steen, een eeuwenoud symbool van de Schotse monarchie, werd naar Schotland teruggebracht in 1996 maar wordt voor de dienst weer overgebracht naar Londen.

Tijdens de kroning wordt de eiken zetel geplaatst in het midden van de middeleeuwse mozaïekvloer die bekend staat als het Cosmati-plaveisel, tegenover het Hoge Altaar, om het religieuze karakter van de ceremonie te benadrukken.

De naamgever van de zetel en de kroon is Edward the Confessor (Eduard de Belijder), de voorlaatste Angelsaksische koning van Engeland, geboren rond 1003, die van 1042 tot zijn dood in 1066 koning was. Onder zijn regering werd het koninklijk paleis gebouwd in wat nu Westminster is en hij liet ook Westminster Abbey bouwen.

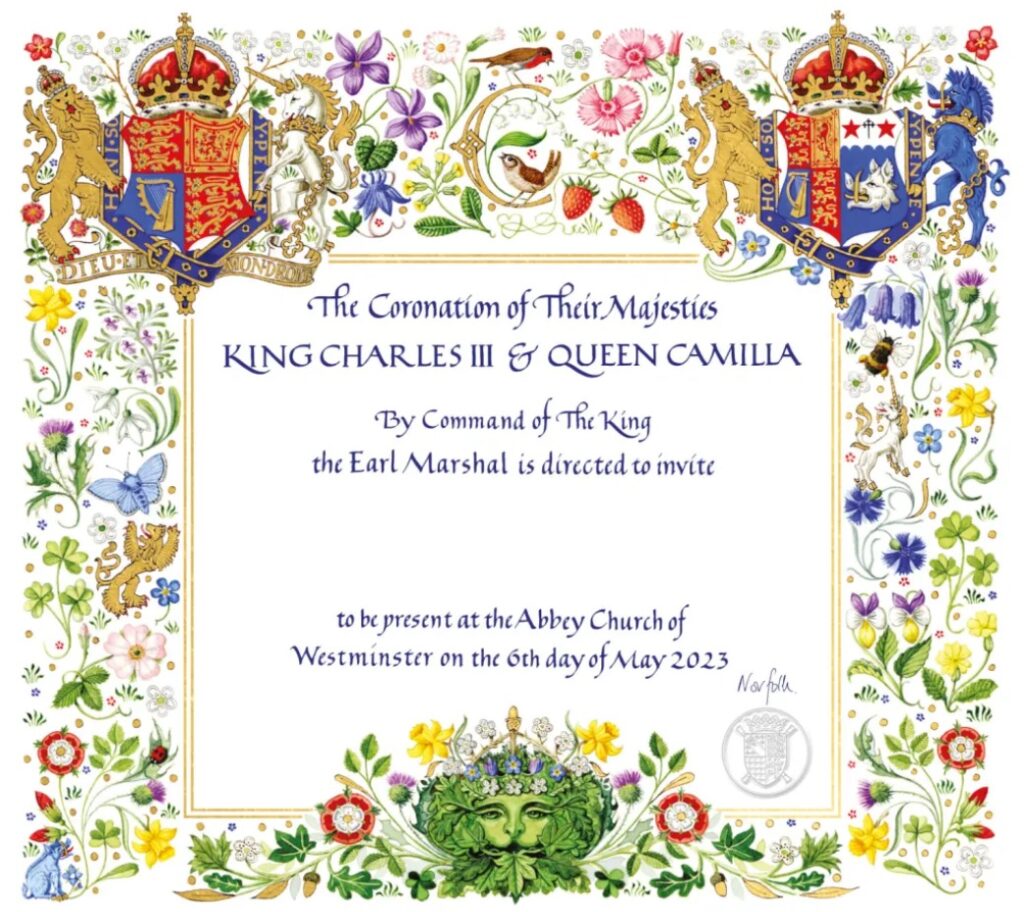

De uitnodiging voor de kroning

Mooi hoor, al die eeuwenoude symboliek waar heel de wereld zich aan zal vergapen. Maar wat opschudding veroorzaakt(e) in Engeland (om het Verenigd Koninkrijk maar even in te korten tot een van de onderdelen ervan), is de uitnodiging die namens Charles werd verzonden voor de kroning. Kijk of het je opvalt wat de tongen losmaakte:

Nee, niet de leeuwen, de geketende eenhoorn en het zwijn, niet de duidelijk herkenbare bloemen, maar de groene man die zo prominent onderaan staat.

Laten we ‘m wat beter bekijken:

Andrew Jamieson ontwierp de uitnodiging en hij is heraldisch kunstenaar, dus heeft verstand van familiewapens, stadswapens en dergelijke. Je zou kunnen denken dat Charles’ groene imago de sleutel is tot alle groen, alle planten en bloemen, en ook de groene man met zijn met (eiken-, meidoorn- en klimop-) bladeren omlijstte gezicht. De koning staat er immers om bekend dat hij als Prince of Wales een grote betrokkenheid toonde bij het milieu, natuurinclusieve landbouw, en andere ‘groene’ zaken. “No wonder our own green King likes him“: geen wonder dat onze groene koning hem leuk vindt’, zegt een krant. Maar andere vertegenwoordigers van de Engelse pers vragen zich af: “Does King Charles’ Green Man make him a pagan?” Is dat wat de Groene Man betekent, dat Charles een ‘pagan’ is, een heiden, paganistisch? Jamieson ziet ‘m als symbool voor het voorjaar, nieuwe geboorte en het nieuwe bewind. Het dessin is gebaseerd op een Britse wildebloemenweide en toont de ‘wapens’ van Charles en Camilla. ‘Whimsical and colourful‘: grillig en kleurrijk.

De Groene Man

De ‘mystieke Groene Man’ zou symbool staan voor wedergeboorte, lente en overvloed, hij zou een figuur zijn uit de Britse folklore, en wordt al eeuwen aangetroffen in (niet uitsluitend) Britse kerken en kathedralen. Ja, zelfs in de Westminster Abbey waar de kroning plaatsvindt is een Groene Man te vinden, omgeven door bladerdecoraties, op het koorscherm dat het schip van de kerk scheidt van het koor. De Groene Man heeft duidelijk een christelijke geschiedenis, al wordt hij ook gezien als een paganistisch symbool, of als een brug tussen paganistische en christelijke ideeën.

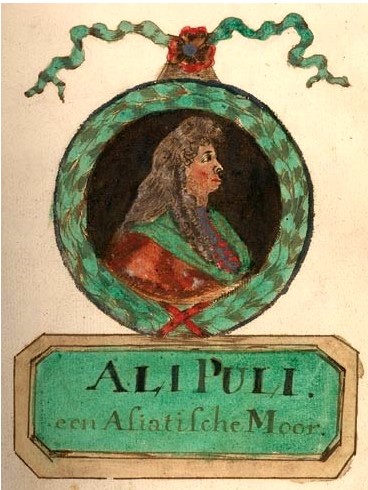

Maar iemand sprong uit zijn vel. Francis Young is een historicus en folklorist die veel van zijn tijd besteedt aan het ontmaskeren van het idee dat de Groene Man een oud fenomeen is uit de Britse folklore. Volgens hem is de figuur pas in de twintigste eeuw ontstaan, en is het geen oud paganistisch symbool. Volgens hem is het te wijten aan amateurhistorica Lady Raglan dat de term ‘Groene Man’ wordt gebruikt in plaats van ‘disgorging foliate head motif’, zoiets als leeglopendbladerhoofdmotief. Zij schreef een artikel onder de titel ‘De “Groene Man” in kerkarchitectuur’ dat in 1939 werd gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift Folklore. “Het motief was deel van een nieuw repertoire dat in Engeland werd geïmporteerd na de Normandische verovering.” Tja, die begon pas in 1066. Dat kun je moeilijk ‘antiek’ noemen. Maar ’twintigste-eeuws’ lijkt me ook geen juiste vertaling.

Hoe dan ook, de Groene Man is een mooi symbool voor zowel groen als paganistisch, zowel christelijk (want ook vaak in kerken aangetroffen) als paganistisch (want natuurreligie, en daarom goed vertegenwoordigd door een figuur met een gezicht van bladeren?) en niet uitsluitend mannelijk (want er zijn ook genoeg ‘Groene Vrouwen’ afgebeeld op plaatsen waar je ook de Groene Man tegenkomt). Lees er het boek van Joke en Ko Lankester maar op na6. Stephen Winick geeft voorbeelden van pre-twintigste- eeuwse verwijzingen naar de groene man in een online artikel’7‘ van 17 februari 2021.

De Orde van de Kousenband

Een nog niet genoemd detail van de uitnodiging is dat Camilla lid is geworden van de ‘Order of de Garter’, de ‘Orde van de Kousenband’. “Een leeuw, een eenhoorn en een beer (mannelijk zwijn) – van de wapenschilden van de koning en koningin – zijn te zien tussen de bloemen. Camilla’s wapen is nu ingesloten door de kousenband, na haar installatie als Koninklijke Dame van de Orde van de Kousenband vorige zomer.”

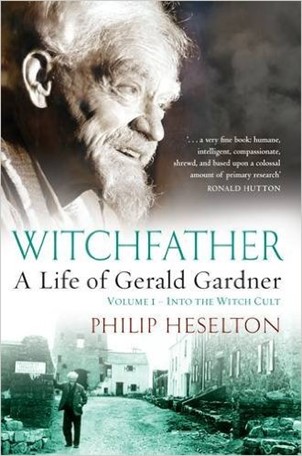

Over de al dan niet paganistische achtergrond van die orde hebben we het in een ver verleden al gehad in een papieren versie van Wiccan Rede, ergens midden jaren ’80. Dat de kousenband in werkelijkheid de ‘garter’ van een heks zou zijn, een hogepriesteres in wicca van wier coven minstens drie covens zijn afgesplitst, zou de verklaring kunnen zijn van het motto van de orde. Dat is namelijk “Honi soit qui mal y pense”, Oudfrans voor: “wee degene die hier slecht van denkt”, “laat niemand er iets slechts van denken”. Maar hoe waarschijnlijk is die oorsprong? Misschien was het verlies van gewoon een sokophouder al schandalig genoeg in 1348, toen zijn nicht en schoondochter Joan van Kent, later de gravin van Salisbury, tijdens een bal haar kousenband verloor. Het ding gleed af en landde rond haar enkels, tot hilariteit van de omstanders. Koning Edward III – alweer een Edward – raapte de kousenband op, deed ‘m om zijn eigen been en sprak: “Schande voor wie er kwaad van denkt” (de meest letterlijke vertaling), gevolgd door: “wie lacht om dit ding, zal er later trots op zijn het te dragen”. En hij richtte de ‘Order of the Garter’ op. Maar ik blijf stiekem denken dat de ‘Fair Maid of Kent’ iets met wicca van doen had. Als je eigenwijs genoeg bent om op je 13e in het geheim te trouwen met een man van 26 zonder de voor beider rang noodzakelijke toestemming, kun je naast je officiële katholieke geloof er wel andere praktijken op nahouden, toch? Mooi verhaal dat de afgezakte kousenband, toen ze ongeveer 20/21 was, zou aantonen dat ze zich met wicca bezighield en zelfs ‘heksenkoningin’ zou zijn. En nou niet aankomen met het verhaal dat wicca pas zoveel later is bedacht of ontstaan! De uitspraak van de koning zou ook geïnspireerd kunnen zijn door omstreden politieke plannen van Koning Edward, en dus een bijbetekenis hebben die gericht was op zijn politieke tegenstanders die daar kwaad van dachten. Hoe saai.

Goddelijk en heilig koningschap

Een goddelijke koning is een term voor een heerser die vergoddelijkt is, of een heidense godheid die wordt vereerd in de gedaante van een koning. Met name de Egyptische farao’s en heilige koningen in andere polytheïstische geloven.

James Frazer schreef8 over de heilige koning, een koning die een zonnegod vertegenwoordigde in een vruchtbaarheidsrite die periodiek werd opgevoerd. Frazer maakte de ‘plaatsvervangende koning’ tot een sleutel in zijn theorie van een universele, pan-Europese en zelfs wereldwijde vruchtbaarheidscultus. Volgens Frazer stelde de heilige koning de geest van de vegetatie voor. Hij kwam tot leven in het voorjaar, heerste gedurende de zomer, en stierf ritueel in de oogsttijd, om weer te worden geboren tijdens de winterzonnewende. De geest van de vegetatie was daarmee een ‘stervende en weer oplevende god’. Osiris, Dionysus, Attis en veel andere bekende figuren uit de Griekse mythologie en klassieke oudheid pasten in dit model. De heilige koning, de menselijke belichaming van deze stervende en wedergeboren vegetatiegod, zou oorspronkelijk een individueel persoon geweest zijn, gekozen om gedurende een bepaalde periode te heersen, maar wiens lot was om aan de aarde te worden geofferd zodat een nieuwe koning in zijn plaats kon heersen.

De heilige koning of koningin kan worden gezien als de belichaming van de godheid op aarde.

Volgens de (Encyclopedia) Britannica9 is het heilig koningschap een religieus en politiek concept waarbij de heerser wordt gezien als een incarnatie, manifestatie, bemiddelaar of vertegenwoordiger van het heilige (het transcendente of bovennatuurlijke rijk). Het concept dateert uit de prehistorie, maar oefent nog steeds een herkenbare invloed uit in de moderne wereld. In een vorm van heilig koningschap werd de koning vereerd als een god, in drie versies. In de vroegste wordt de hoofdman/het opperhoofd beschouwd als goddelijk. In de belangrijkste versie zien we de god-koninkrijken van grote rijken zoals die van het antieke Midden-Oosten en Oost-Azië, van antiek Iran, en het Midden- en Zuid-Amerika van vóór Columbus. De secondaire versie bestond in het Perzische en Hellenistische rijk (Grieks-Romeinse cultuur) en in Europese rijken. Er bestaan ook tussenvormen. Frazer richtte zich voornamelijk op de middelste, voornaamste vorm.

Naast de heerser als god zelf of een menselijke vorm van de god, is er de optie dat de koning wordt beschouwd als zoon van god. En de koning kan god worden als hij overlijdt.

De gebruikelijke functie van een heilige koning is om zegen te brengen voor zijn volk en het land waarover hij regeert. Omdat hij een bovennatuurlijke macht heeft over het leven en welzijn van zijn stam, wordt geloofd dat het opperhoofd of de koning de vruchtbaarheid kan beïnvloeden van de bodem, het vee en de mensen, maar vooral het brengen van regen. Hij heeft macht over de natuurkrachten. Als de stam of het land wordt getroffen door ongeluk, een epidemie, honger, misoogsten of overstromingen, kan de koning verantwoordelijk worden gehouden.

De vaak gewelddadige offerdood van de heilige koning, de zoon van de koningin, of van de godin in de steentijd, was het belangrijkste onderdeel van een archaïsch ritueel dat periodiek de verzoenende invloed van de onzichtbare krachten en energieën van de Aardegodin op kosmosvernieuwing en de onzuiverheden en zonden van de stam nastreefde. Het was een van de primitieve culturen en de meest karakteristieke ‘religieuze’ gebeurtenissen in de wereld die de relaties van de latere mens met het ‘heilige’ rijk markeerden10.

De Heilige Koning is een ‘mannelijk’ aspect, maar archetypen manifesteren zich in meerdere geslachten en genders. Er waren ook heilige koninginnen (sacred queen) en godin-koninginnen (goddess queen). Met dat woord wordt een staatsvrouw aangeduid die alle staatsbevoegdheden bezit en religieuze betekenis heeft voor haar achterban. En dan had je nog de ‘queen of heaven’ (Inanna, Anat, Isis, Nut, Astarte, en mogelijk Asherah) en de koningin van de goden zelf (Hera of Juno).

De gewijde koning van Engeland en zijn bruid

Maar ik wil nog even terug naar modernere tijden. In ‘Breaking the Vessels: de desacralisering van de monarchie in het vroegmoderne Engeland’ 11, lezen we:

Bij zijn executie in 1649, bleef Charles I in de ogen van menigeen een goddelijke koning, ondanks het feit dat het concept van een door priesters aangemerkte of bekrachtigde monarch botste met de idealen van de Reformatie. … De berechting en terechtstelling van Charles I was de schandaligste politieke gebeurtenis van de zeventiende eeuw. … In het bijzonder werd het vergieten van heilig bloed als een gruwel beschouwd. ‘Touch not the Lord’s anointed’ (‘Raak niet de gezalfde van de Heer aan’), het motto van de koninklijke pamflettisten gedurende de burgeroorlog, weerspiegelde de diep ingewortelde overtuiging van de vorst als een gewijde figuur.

De vorst is hier meer een gewijde dan een goddelijke koning, maar in de ogen van velen dus wel degelijk van speciale betekenis. Misschien geldt dat in het Verenigd Koninkrijk meer dan elders.

Ik heb in de stukken die ik vond over (de fasen van) de kroning niets teruggevonden over de ‘bruiloft’ van de koning met het land, maar als je ernaar zoekt, dan blijkt ook dat gebruik nog steeds te bestaan. Koning Charles III zal de ’trouwring van Engeland’ ontvangen alvorens hij gekroond wordt. Tijdens de kroningsplechtigheid wordt de ring om de vierde vinger van de vorst geschoven door de aartsbisschop, als een symbool van zijn ‘koninklijke waardigheid’. De ‘Sovereign’s Ring’ ofwel de ‘The Wedding Ring of England’ zou dateren van Edward de belijder, die had bedongen dat de ring voor alle toekomstige kroningen zou moeten worden gebruikt. In feite werd voor iedere nieuwe vorst een nieuwe kroningsring gemaakt, tot in 1831 de huidige ring werd gemaakt voor de kroning van William IV in 1831. Alle latere vorsten zijn gekroond terwijl ze deze ring droegen, behalve Victoria, die te kleine vingers had. De ring, een van de kroonjuwelen van Engeland, heet de trouwring omdat hij het huwelijk van de vorst met de natie vertegenwoordigt. Het design12 is een afspiegeling van de nationale vlag. Een recht rood kruis tussen vier saffieren is het Kruis van Sint-Joris (St George), dat de Engelse vlag vormt (én voorkomt in het embleem van de Orde van de Kousenband). De diamanten en saffieren verwijzen ook naar de kleuren van de Britse vlag (die van het hele Verenigd Koninkrijk dus). Op die manier verbeeldt de ring het ‘huwelijk’ van de vorst met zijn land. Het ziet er niet naar uit dat tegenwoordig dit huwelijk geconsummeerd wordt (dat is met dubbel m), of alleen ‘in token’, symbolisch. Maar dat een fysieke daad waarschijnlijk wel de oorsprong was, brengt ons weer bij de (lady) ‘sovereignty’ waarmee we begonnen.

Lady Sovereignty

De Oxford Reference: “De personificatie van de macht en het gezag van een koninkrijk als een vrouw die seksueel gewonnen moet worden, dateert van vóór literatuur in een Keltische taal. In de hiërogamie [Gk hieros, heilig; gamos, huwelijk] beschreven in een Sumerische hymne (2e millennium v.Chr.), moet de koning op nieuwjaarsdag in haar residentie paren met Inanna, koningin van de hemel en godin van liefde en vruchtbaarheid. In de hymne wordt de koning gezien als een incarnatie van Dumuzi, een herder-koning en echtgenoot van Inanna, en zo eindigt de rite van hiërogamie met zijn extatische seksuele vereniging met haar, misschien in werkelijkheid uitgevoerd met een van Inanna’s heilige prostituees.”

Voor zowel de vroege Indo-Europese cultuur als de twaalde-eeuwse Keltische tradities (Tara, Ierland) is bewijs van seksuele soevereiniteitsrituelen: de spirituele en/of fysieke seksuele vereniging tussen de mannelijke koning en een goddelijke vrouwelijke soevereiniteit. “Verhalen over de vrijpartij van een (potentiële) koning met de godin van de soevereiniteit zijn zo wijdverspreid in het vroege Ierland en elders in Europa, zoals Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘Wife of Bath’s Tale’, dat ze hun eigen internationale volksmotiefnummer, D732, verdienen13.”

(In ‘De nevelen van Avalon’ gebruikt Marion Bradley precies dit motief om te verklaren waarom de Arthur-sage zo slecht afloopt. Morgaine, die priesteres van dienst bleek in de heilige vereniging van haar eigen broer met zijn koningschap, is nogal geschokt en verward na deze gebeurtenis. De zoon die – in de roman van Bradley – uit deze ontmoeting voortkomt, brengt uiteindelijk Arthur ten val.)

Ik wil eindigen met een verwijzing naar een christelijk boek: ‘God Save the King: The sacred nature of monarchy’ door Ian Bradley (predikant in de Kerk van Schotland en emeritus hoogleraar culturele en spirituele geschiedenis aan de St Andrews University), zoals dat wordt besproken door ‘The Rt Revd Graham James’, voormalig bisschop van Norwich en nu ere-assistent-bisschop in het bisdom Truro in een artikel14 van 28 april. Graham James vraagt zich af: is er nog plek voor een gezalfde vorst? Het Verenigd Koninkrijk is inmiddels immers grotendeels seculier. Geen andere Europese vorst heeft een kroningsdienst. Alleen de Noorse koning of koningin ontvangt een zegening. “De kroningseed van onze eigen vorsten om ‘de protestantse gereformeerde religie die bij wet is ingesteld’ hoog te houden, wordt afgelegd in een sacramentele context met zalving en heilige communie, waarbij wordt gesproken over continuïteiten die teruggaan tot ver voor de Reformatie.”

De liturgie die op 6 mei gebruikt zal worden, is gebaseerd op de ritus van St Dunsta, aartsbisschop van Canterbury in 973. Er is zelfs nog een oudere link in de vorm van de zalving. De olie (ook nu nog speciaal bereid en gewijd in Jerusalem15) verwijst naar de oude koningen van Israël, die werden gezalfd vanwege hun toewijding aan hun volk en aan God.

Ian Bradley gelooft dat de monarchie hét instituut kan zijn dat de verschillende volken in het VK kan verenigen. Hij gelooft dat de rol die de vorst speelt vooral heilig is. Hij pleit dat het symbool staat voor spirituele waarden, de orde en stabiliteit bevordert te midden van de chaos, staat voor publieke belangen tegenover privé-belangen, geloof vertegenwoordigt tegenover materialisme en fungeert als een brandpunt voor eenheid, in een steeds verder versplinterende samenleving.

Peilingen wezen uit dat tweederde van de Britse bevolking in 1953 geloofde dat de vorst(in) direct was gekozen door God. Dat is heel recent. In die zin is het logisch dat de Britse kroningsceremonie nog steeds ‘sacraal’ van aard is. Maar de kroning van Elizabeth II, op 2 juni 1953, werd, heel seculier – en een nieuwe fenomeen – op haar verzoek live getoond op de televisie. Opdat iedereen het zou kunnen meemaken. De hele stam, het hele volk. Terecht!

Noten

1 The Western Way. A practical guide to the Western Mystery Tradition. Volume 1, The native tradition. Caitlín and John Matthews, Arkana, 1985, p. 39-41

2 Hier wordt verwezen naar het boek Symbols of Sovereignty van B. Barker. Westbridge Books, 1979.

3 Hier wordt verwezen naar Celtic Mythology van P. MacCana. Hamlyn, 1970.

4 Zie verder The initiation of the underworld van B. Stewart, Aquarian Press, 1985.

6 Recensie elders in dit online magazine en zie ook https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2021/02/what-was-the-green-man/

7 What Was the Green Man? https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2021/02/what-was-the-green-man/

8 In The Golden Bough, 1890. Korte versie uit Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_king

9 Zie https://www.britannica.com/topic/sacred-kingship en https://www.britannica.com/topic/sacred-kingship/Functions-of-the-sacred-king-the-king-as-the-source-of-cosmic-power-order-and-control

10 The ‘Sacrifice of the Sacred King’. Myth, ritual and meaning. Eliseo Ferrer. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358879068_Eliseo_Ferrer_The_Sacrifice_of_the_Sacred_King_Myth_ritual_and_meaning

11 Breaking the Vessels: the Desacralization of Monarchy in Early modern England. Robert Zaller, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Autumn, 1998), pp. 757-778, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2543687

12 Zie een afbeelding op https://www.rct.uk/collection/31720/the-sovereigns-ring

14 God Save the King: The sacred nature of monarchy. Ian Bradley. Darton, Longman Todd, £8.99. ISBN 978-1-915412-52-2. Besproken in Church Times, 28 April 2023, https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2023/28-april/books-arts/book-reviews/god-save-the-king-the-sacred-nature-of-monarchy-by-ian-bradley

15 Sacred coronation oil will be animal-cruelty free https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-64836101. Zie verder bijvoorbeeld BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-65342840, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-63543019 en volg de links naar andere pagina’s.