Part Two – The Goddess and the Maiden

To attempt an overall comparison of Bahá’í and Pagan development in the second half of the twentieth century would require a study much larger than this, consequently only the issue of women and feminism will be scrutinised in relation to relevance and numerical growth.

Women – the Divine Feminine

Both Wiccans and Bahá’ís reject a patriarchal, masculine God, in the case of Wiccans whilst there are differing opinions about the nature of the divine, the centrality of a goddess to Wicca was ensured by Gardner’s recounting of “The Myth of the Goddess”[1] and his description of the Drawing Down the Moon ritual. Gardner’s work was not isolated but drew heavily upon the work of a number of anthropologists who had hypothesized that prior to the arrival of Christianity all of Europe had worshipped a single great goddess. Whilst this theory was popular in the early twentieth century no witch trail cited worship of a goddess in evidence. It does not therefore appear to be a factor earlier than the Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries, however this feminising of the deity was to prove exceptionally important in the production of relevance for feminists, who would pay a significant role in the development of American Paganism.

In the Bahá’í Writings Baha’u’llah refers throughout to The Holy Maiden, who represents the remembrance of God. The Holy Maiden is an undoubtedly female symbol. She is sometimes represented as a bride of either the Báb or Bahá’u’lláh, such as in the Hidden Words.[2] Many of the references to her appear in texts that are still untranslated into English. A number of these references to “maids of Heaven” might be analogous with the “black eyed maidens” of the Qu’rán, but the parallel is probably only superficial. The Maid of Heaven, or Holy Maiden, plays an especially important part in Bahá’u’lláh’s visionary, allegorical writings during His stay in Baghdad.

Bahá’u’lláh states that He had a vision of the Maiden whilst imprisoned in the Black Pit in Tehran during 1852-3. He recounts the vision in the “Sura of the Temple,”

“While engulfed in tribulations I heard a most wondrous, a most sweet voice, calling above My head. Turning My face, I beheld a Maiden – the embodiment of the remembrance of the name of My Lord – suspended in the air before Me”[3]

The Maid of Heaven thereafter appears as a personification of the spirit of God throughout Bahá’u’lláh’s writings. She next appears in the “Ode of the Dove,” a two thousand verse poem which Bahá’u’lláh wrote at the request of Kurdish divines. The poem is about the relationship between the Manifestation of God and the Most Great Spirit. It takes the form of a dialogue between Bahá’u’lláh and the Holy Maiden. Bahá’u’lláh praises and glorifies the Holy Maiden and dwells on His past sufferings, He speaks of His loneliness and grief, whilst affirming His resolution to continue with His ministry.[4]

The “Tablet of the Maiden” continues this theme. Again, two figures appear in the drama: Bahá’u’lláh, as the Supreme Manifestation of God, and the Holy Maiden, symbolising some of the attributes of God previously hidden from humankind. In the course of the dialogue between the two, Bahá’u’lláh recounts His afflictions and describes the uniqueness of His station.[5] Other tablets from this period, such as the “Tablet of the Deathless Youth,” and the “Tablet of the Wondrous Maiden,” also contain the symbolism of the Holy Maiden. All convey the glad tidings of the new revelation in highly allegorical language, with the symbol of the Holy Maiden representing the spirit of God.[6] None of them have been translated into English; English-speakers find the most familiar references to the Holy Maiden in the Hidden Words (Persian number 77) and “The Tablet of the Holy Mariner.”

Later works such as the “Súratu’l Bayán,” revealed in 1873, are rather different in style from Bahá’u’lláh’s Baghdad writings. Lamentation and torment are replaced by triumph and glorification of a new revelation.

“Step out of thy Holy chamber, O Maid of Heaven…drape thyself in whatever manner pleaseth Thee…. Unveil Thy face and manifest the beauty of the black-eyed damsel…”[7]

These passages are quoted because superficially the expectation that a belief system stemming from the strictly monotheistic Islamic tradition and Wicca with its roots (authentic or otherwise) in pre-Christian polytheism, would be highly divergent in their conception of the godhead, however, the union of Baha’u’llah and the Holy Maiden is similar the union of the God & Goddess described by Gardener[8]. Furthermore, Gardner stated that a being higher than the God and the Goddess was recognised by the witches as the “Prime Mover”, but remains unknowable[9] Patricia Crowther also referred to this supreme godhead as Dryghten[10] and Scott Cunningham called it “The One”[11]. This mirrors the belief in an “Unknowable God” above and beyond human understanding[12], indeed, it is impossible to even hint at the nature of God’s essence[13] according to Baha’u’llah. The similarities of theological understanding mean that relevance would be produced by both traditions for people with a similar view of the Divine, this does not mean that they would be in direct competition for converts as the Wccans were not seeking them and the Bahá’ís did not stress this element of their beliefs in teaching programmes.

The Role of Women

In both Wicca and Bahá’í there have been an extraordinary number of important and prominent women. Perhaps the most significant of the early scholars was Fatimah Baraghani (1814 – 52) known by many names including Quratu’l Ayn and Tahirih. Most unusually for a woman she was a recognised as a major scholar of Islam and a poet, she accepted the teachings of the Bab and became one of his most charismatic disciples. She was of major importance in the radicalisation of the Babi movement and her removal of her veil was of both symbolic and political importance. She was martyred in September 1852. Little of her writing remains but her poetry is highly regarded in Persian literary circles. One of the surviving poems of Tahirih that celebrates life and a time of renewal may actually have been written on Naw-Ruz, the Persian and festival which falls on the Spring Equinox, as she refers to the day in the poem.[14]

This poem is again an erotic allegory and the idea of spring as a male lover being reawakened is familiar in Pagan tradition. Here again, is shared imagery and symbolism, which might be argued, would produce relevance for a similar context.

Feminism

The first phase of feminism is usually related to the struggle for suffrage for women and amongst the early British Bahá’ís Women’s suffrage was an important issue; numerous members of the group can be identified as active in the suffrage movement. The best known from the Bahá’í point of view of the suffragists is Lady Sarah Blomfield. Both she and her daughters were involved with the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). In 1914 as part of a mass protest against force-feeding of prisoners, Mary Blomfield (Mary Basil Hall) used her presentation at court to address the king; H. R. H. George V. Christabel Pankhurst describes it thus:

“A deputation to the King did enter Buckingham Palace after all and the King heard our petition. The deputation consisted of one girl, Mary Blomfield, daughter of Sir Arthur Blomfield, a friend in his day of King Edward, and granddaughter of a Bishop of London. As Mary Blomfield, at her presentation at Court, came before the King, she dropped on her knee, with her sister Eleanor standing by her, and in a clear voice claimed votes for women and pleaded: ‘Your Majesty, stop forcible feeding.” [15]

Her sister, Sylvia also mentions the incident and refers to Lady Blomfield and her involvement with the Bahá’ís, neither of which seem to impress her overmuch,

“At a Court function afterwards, Mary Blomfield dropped on her knees before the King and cried “For God’s sake, Your Majesty, put a stop to forcible feeding!” She was hurried, as the Daily Mirror put it, from “the Presence,” which, so the public was relieved to learn, had remained serene. Lady Blomfield intimated to the Press her repudiation of what her daughter had done. Lady Blomfield had been enthusiastic for the militancy of the most extreme kind, so long as it was committed by other people’s daughters. She had come to me at a Kensington WSPU “At Home,” shortly after my release in 1913, expressing her delight that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, of whom she was proud to call herself a follower, had spoken with the sympathy of the Suffragettes; he had suffered forty years imprisonment, she told me ecstatically, for preaching the unity of all religions and the brotherhood of man. Under his teaching, she had lost all regard for the pomp and vanities of earthly existence.”[16]

Also involved with the WSPU was Elizabeth Herrick (1864 – 1929). In an unpublished and anonymous biography in the Bahá’í archives it is stated:

“Elizabeth Herrick placed herself as a soldier at the disposal of the Pankhursts; one day in obedience to orders went into Kensington High Street with a little hammer and broke a window. She spent her birthday that year in Holloway Prisons and when she came out her business was ruined. She had again flung material success to the winds for the sake of a spiritual idea.”[17]

Herrick’s involvement with the WSPU is confirmed by mention of her imprisonment for two months hard labour in the suffrage periodical Votes for Women. The sentence was light because the damage inflicted on the windows of a government building was worth “not more than a few shillings.”[18] She is also referred to under her professional name of “Madame Corelli” donating hats to WSPU fund raising sales from 1911 onward.

Another important link between Bahaism and feminism was Charlotte Despard. Mrs. Despard, during her long and eventful life embraced every radical cause from vegetarianism to women’s suffrage, from Sinn Fein to sandal wearing.[19] It is a mark of her farsightedness that most of the causes she espoused, with the possible exception of sandal wearing, have either been won or are now seen as mainstream. It is not known when she first became involved with the Bahá’í Movement, or through whom, but her path crisscrossed that of others involved in the Movement again and again. Between 11 and 26 August 1911, she addressed a Theosophical Society summer school, on “Some Aspects of the Women’s Movement.” Wellesly Tudor Pole was also there, his topic — “Bahaism.” In September 1911, the Women’s Freedom League newspaper The Vote ran a three-part article by Despard entitled “A Woman Apostle in Persia”[20] but this account of Táhirih, significantly, does not describe her as a suffragette. She addressed a meeting at the Clifton Guest House, owned by the Pole family and where ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would stay when in Bristol, on Friday 15 March 1912. Her subject was the Women’s Movement.[21] The fourth International Summer School organized by The Path advertised Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), (who would play an important role in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit to Edinburgh) Despard and Stapley as speakers was advertised in the Christian Commonwealth on 12 July 1912. A prominent supporter of the WFL was Reginald Campbell, the minister of the City Temple, who wrote a pamphlet for the WFL. The publication of his church The Christian Commonwealth frequently carried reports of WFL activities and advertisements and vice versa. A number of other people within the Bahá’í circle can be connected to the suffrage and feminist movements. Wellesley Tudor Pole’s Clifton oratory was visited by a number of leading suffragettes including Annie Kenny and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (1867-1954).[22] Mary Allen, the elder sister of Janet and Christine Allen, who with Kitty Tudor Pole formed the triad of maidens around the vessel in the oratory was deeply committed to the WSPU. She was imprisoned and went on hunger strike for political prisoner status. Constance Elizabeth Maud who wrote a book about the Bahá’ís entitled Sparks among the Stubble, also wrote about the suffrage cause in a book called No Surrender.

When the struggle for the vote was won for the most part feminism declined as a political and social force, at the time of Gardner’s publication (1954) the role of women was perhaps more firmly entrenched as homemaker and wife than at ant other time in the twentieth century. Whilst Wicca produced numerous influential female figures most notably Doreen Valiente (1922 – 1999), Sybil Leek (1917 – 1982), and Maxine Saunders none of these were overtly feminist, in fact despite the importance of the goddess(es), the role of high priestess and the traditional identification of the term “witch” with women, the early Gardnerians seem apolitical and if anything, slightly right of centre. By the 1950’s the Bahá’ís in Britain were consumed with the campaign to spread the Bahá’í Faith throughout Africa, their teachings were mainly promoted in the form of a number of social principles, including racial and sexual equality. The number of women dominating the leadership and the community began to decline and it was single men and couples who would “pioneer” to Africa.

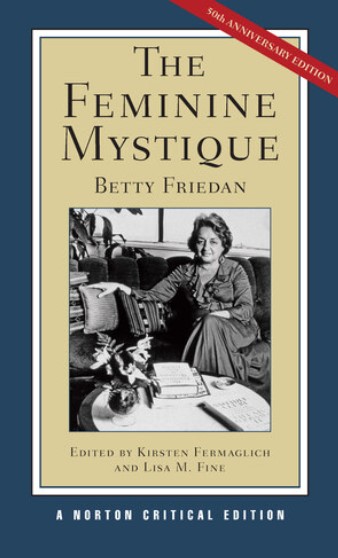

(The first student edition of Betty Friedan’s national bestseller was published in honour of its fiftieth anniversary. The Feminine Mystique forever changed America’s consciousness by defining “the problem that has no name.”)

The Second Phase of Feminism is usually dated from the mid 1960’s, in the United States the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963 might be argued to signal the start of the Women’s Liberation Movement against the backdrop of the Civil Rights and Anti Vietnam War demonstrations. This second wave of feminism involved not just legal rights but raised the issue of the relationship between the personal and the political. In the British Isles it can be dated from the 27 and 28 February and 1 March 1970 when women’s groups from around the country met at the first National Women’s Liberation Conference at Ruskin College, Oxford to discuss the challenges facing women and the liberation movement and to work out a series of demands.

One of the most esteemed theorists of the roots of women’s oppression was Frederick Engles who had argued in Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State that an early stage of human social development was “primitive communism” a hunter gatherer society in which women took an equal role with men, before the development of private property led to patriarchy. This hypothesis gave a respectable revolutionary veneer to Murray’s matriarchal goddess society and a number of Marxist historians incorporated elements of her work into their own. Two highly influential feminist writers Andrea Dworkin and Mary Daly both began to consider the claims of WITCH (Women’s International Conspiracy from Hell) a New York group which had published a manifesto in 1968 which stated that witchcraft had been the religion of all Europe before the arrival of Christianity and that for centuries afterwards it had survived amongst the poor. Its suppression could therefore be viewed both in terms of class and in the subjugation of women. Daly and Dworkin repeated these assertions but initially saw witchcraft primarily as an obstacle to the patriarchy rather than a religion[23].

In 1973 a book entitled Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers[24] was published, in a single stroke not only was the “wise woman” reinvented as a feminist, but the demonisation of the male-dominated medical profession, already distrusted because of the abortion debate, was completed. In 1976 Merlin Stone published When God was a Woman[25] restating the great goddess theory and repackaging it for feminist consumption, put very simply feminists found relevance in witchcraft and its suppression, the “Burning Times” might be argued to have a particular relevance for white, middle-class women seeking a mantle of victimhood. Wiccans, Pagans and/or witches did not seek out feminism, I have been unable to locate any specifically “feminist” writings from Pagans prior to the publication of Daly’s seminal Gyn/Ecology in 1978, however, the extent of relevance is such that in the 1980’s the dominant writers in the field addressed feminism from a Pagan perspective. The first of these was a Hungarian living in the United States and calling herself Zsuzsanna Budapest[26], and Starhawk[27] a particularly talented writer whose books have sold in huge numbers. Such was the dominance of these Pagan writers that whilst there is a sharp decline in feminist publications generally the women’s spirituality genre seems buoyant.

The 1990’s saw the emergence of “Feminist Theology” a scholarly development by which various religious traditions fought for the soul of feminism. With a pagan perception of history now firmly entrenched within feminism more traditional religions were forced to make themselves relevant to women’s spirituality. Christians, in particular the Anglicans, rallied by success of the Movement for the Ordination of Women attempted to “rediscover” the feminist intentions of the founders of their faith. Biblical tradition and interpretation were reevaluated by scholars such as Phyllis Trible[28] in Texts of Terror, while Karen Armstrong[29] and Rosemary Radford Ruether[30] took on Christian history and the Church Fathers, some were apologists like Elaine Storkey[31], and others like Mary Daly abandoned the Church for the goddess. Overall, although traditional monotheism put up a spirited attempt at feminisation the majority of those in the pews still seem to prefer their religion patriarchal.

The Bahá’ís had been unable to react to the second wave of feminism in the way they had to the first. The Bahá’í teachings on marriage, sexuality, sexual orientation and abortion were well-known within the Bahá’í community and they did not reflect the thinking of the Women’s Liberation Movement[32]. Whilst individuals might have been initially attracted to the Bahá’í Faith’s radical sounding social principles, they may have lost interest when they discovered the only acceptable form of sexual expression for Bahá’ís is within marriage and that marriage is only permissible with parental consent.[33] In 1979 the Iranian Revolution meant that the Bahá’ís were faced with persecution and uncertainty in the land where their Faith began, many Persian s fled their homeland and settled in the West, whilst this migration would ultimately bolster the communities, an influx of Persian refugees was unlikely to push feminism higher on the agenda. The Bahá’ís did make some attempt to address issues raised by feminist theology, there were, after all fairly well placed with the Holy Maiden iconography, the historic commitment to women’s equality and apart from the membership of the Universal House of Justice issue, a good record of women in leadership roles. In 1994 The Association for Bahá’í Studies dedicated an issue of its journal[34] to feminist theology and whilst a number of interesting articles were published it was of little interest to ordinary s because it feminist theology failed to become relevant to the main current of Bahá’í thinking.

Conclusion

In considering why the Wiccan/Pagan movement has been so much more numerically successful in the United Kingdom the Theory of Relevance would suggest that over the last half-century the Wiccan/Pagan movement has swum with the tide of relevance, while the Bahá’ís have swum against it. Whilst there were significant overlaps in both beliefs and personnel at the start of the twentieth century the Bahá’ís “stalled” and failed to address the issued raised by second and third-phase feminisms and feminist theology, conversely Pagan writers were able to “steal their clothes” and present a radical politicized version of female spirituality, ironically in the tradition of Tahirih. The Pagans have been assisted by the fact that the two most important issues of the last half of the twentieth century have been feminism and the environment, issues which were and are integral to Pagan world view and consequently maximized relevance.

The Bahá’í s have created an exclusivist and highly structured organisation where plans and strategies are relayed through a “top-down” administration with varying levels of success, conversely, the Pagan movement, unconstrained by administration and critical (in some cases) of structures has flourished and become increasingly inclusive. The prohibition on political activism for s has meant that whilst the widespread acceptance of some of the Bahá’í principles might have encouraged growth the inability to be involved in radical movements may have restricted it, conversely American writers like Starhawk have introduced a political dimension to Paganism which has further increased its relevance to activists. The limited moral and ethical teaching of Paganism has meant it has a resonance with the relative morality of post Christian Britain. Perhaps the widest gulf between modern Pagan and Bahá’í traditions is that the former having outgrown the constraints of Gardnerian orthodoxy is now a widely divergent form of personal spirituality, none of its adherents have any ambition for it to be anything else. The Bahá’í Faith, however, is consciously promoted as not just a spiritual path but a model for future civilization, with laws and organisational structures.

Only time will tell which is the model of religion for the twenty-first century.

By Lil L.C. Osborn.

Bibliography

Abdo, LCG. “Religion & Relevance, the Bahá’ís in Britain 1899 – 1930.” PhD thesis, SOAS, London University, 2004.

Armstrong, Karen, A History of God: the 4000-year quest of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam: New York: Ballantine Books, 1994

Bahá’u’lláh. Hidden Words. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1975.

Bahá’u’lláh. Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1986.

Bahá’u’lláh. The Kitab – i- Iqan; The Book of Certitude. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982.

Bahá’u’lláh. Gleanings. London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1978.

Benham, P. The Avalonians. Glastonbury: Gothic Image, 1993.

Budapest, Zsuzsanna, Grandmother Moon, San Francisco: Harper, 1991

Crowther, Patricia. Witch Blood! The Diary of a Witch High Priestess! New York: House of Collectibles, 1974.

Cunningham, Scott. Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. St. Paul: Llewellyn, 1988.

Daly, Mary. Gyn-ecology. Boston: Beacon Press, 1990.

Ehrenreich, B & English, D. Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers: New York, The Feminist Press, 1973.

Fortune, Dion. Aspects of Occultism. Wellingborough: Aquarian Press, 1978.

Gardner, Gerald B The Meaning of Witchcraft. Lakemont, GA: Copple House Books, 1988.

Hainsworth, Philip. “Bahá’í Story,” n.d. MS. National Bahá’í Archives, London

Hainsworth, Philip. Looking Back in Wonder. Stroud: Skyeset, 2004.

Hesleton, Phillip. Gerald Gardner & the Cauldron of Inspiration. Milverton: Capall Bann, 2003.

Hornby, Helen ed., Lights of Guidance, New Delhi: BPT ,1983.

Hutton, Ronald. Triumph of the Moon. Oxford: OUP 1999.

Momen, Wendi, ed., A Basic Bahá’í Dictionary. Oxford: George Ronald, 1989.

Pankhurst, Sylvia. The Suffragette Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals London: Virago, 1977.

Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled: The Story of How We Won the Vote London: Cresset Women’s Voices, 1987.

Radford Ruether, Rosemary. Sexism and God Talk: Boston, Beacon Press, 1983

Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. Relevance, Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986.

Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, New York:Harper Row, 1979

Stone, Merlin. When God was a Woman. New York: Harvest Books, 1976.

Storkey, Elaine. What’s Right with Feminism? London, SPCK, 1985.

Taherzadeh, A. The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, vol. 2, Oxford: George Ronald, 1988.

Trible, Phyllis. Texts of Terror, Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984.

[1] Witchcraft Today p.41

[2] Bahá’u’lláh, Hidden Words (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1975) Persian number 77.

[3] Bahá’u’lláh, Hidden Words (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1975) Persian number 77.

[4] A. Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, vol. 2, (Oxford: George Ronald, 1988) 63

[5] Ibid, 125

[6] Ibid, 213, 218.

[7] Bahá’u’lláh, “Tablet of the Holy Mariner,” in Writings of Bahá’u’lláh (Delhi: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1986) 714.

[8] Gerald B Gardner, The Meaning of Witchcraft. (Lakemont, GA: Copple House Books 1988) 260-261.

[9] Gerald B Gardner, Ibid pp 26-27

[10] Patricia Crowther, Witch Blood! The Diary of a Witch High Priestess! (New York City: House of Collectibles, 1974)

[11]Scott Cunningham, Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner (St. Paul: Llewellyn, 1988).

[12] Baha’u’llah, The Kitab – i- Iqan; The Book of Certitude, trans. Shoghi Effendi, 3rd edition, London BPT, 1982 (1st ed. (USA) 1935) p.63

[13] Baha’u’llah, Gleanings trans. Shoghi Effendi, , London BPT, 1978 (1st ed. (USA) 1935) pp. 3-4, no.1

[14] see Tahirih: A Portrait in Poetry trans. by Amin Banani and Anthony A. Lee, (Los Angeles: Kalimat Press)

[15] Christabel Pankhurst, Unshackled: The Story of How We Won the Vote (London: Cresset Women’s Voices, 1987), 277.

[16] Sylvia Pankhurst, The Suffragette Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (London: Virago, 1977), 554.

[17] “Biography of Elizabeth Herrick,” n.d. MS. National Bahá’í Archives, London.

[18] [Suffragist Cases in Court], Votes for Women (London) (15 March 1912), [p.380]

[19] Despard’s sandals were made by Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), the writer on, amongst other issues, homosexual rights. He also wrote about sm in Pagan & Christian Creeds (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920).

[20] Charlotte Despard, A Woman Apostle in Persia,” The Vote (London) (30 Sept., 7 Oct., and 14 Oct. 1911).

[21] “Mrs Despard at Clifton,” Christian Commonwealth (London) (27 March 1912), p. 428.

[22] Patrick Benham, The Avalonians (Glastonbury: Gothic Image, 1993) 109.

[23] Hutton p.343

[24] Barbara Ehrenreich & Deirdre English, Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers New York, The Feminist Press

[25] Merlin Stone, When God was a Woman York: Harvest Books, 1976.

[26] Zsuzsanna Budapest, Grandmother Moon (San Francisco: Harper, 1991)

[27] Starhawk, The Spiral Dance (New York:Harper Row, 1979)

[28] Phyllis Trible, Texts of Terror, (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984)

[29] Karen Armstrong, A History of God (New York: Ballantine Books, 1994)

[30] Rosemary Radford Ruether, Sexism and God Talk ( Boston: Beacon Press, 1983)

[31] Elaine Storkey. What’s Right with Feminism? (London: SPCK, 1985)

[32] I have discussed the failure of the Faith to address second wave feminism elsewhere, Lil Abdo, “An Examination of Androgyny and Sex Specification in the Kitab-i-Aqdas,” Fourth Irfan Colloquium, De Poort Conference Center, Netherlands, November 1994. Lil Abdo, “Possible Criticisms of the Bahá’í Faith from a Feminist Perspective,” Eighth Irfan Colloquium, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, U.K., December 1995.

[33] There is some evidence of short term growth in the Bahá’í community in the 1970s, the difficulty appears to have been in retaining rather than attracting converts.

[34] The Bahá’í Studies Review Vol. 4, No. 1 1994

Published with permission from the author Lil L.C. Osborn.

BIO: Who is Lil L.C. Osborn?

I have a BA in Arabic and Islamic Studies and an MA in Women and Religion both from the University of Lancaster. My PhD was awarded by the University of London, School of Oriental & African Studies for a thesis examining the history of the Baha’i Faith in the British Isles.

I have also undertaken a Farmington Fellowship at the University of Oxford where I used my role as a teacher of Religious Education in a school for ASC learners to research links between Autism, Black Metal and Satanism.

My research interests are Islamic and post-Islamic magic, early twentieth-century European esoteric groups, in particular their links with the Middle East, Wicca & Paganism.

I am currently researching the link between feminism/suffrage and the Divine Feminine in the context of esoteric groups including the Baha’is in Britain. I have homes in London and Somerset.

See: https://independent.academia.edu/LilOsborn

PART 1