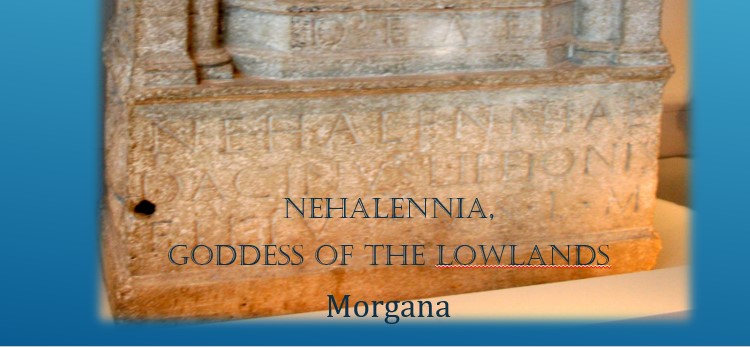

Recently, in the 1970’s, many Nehalennia votives washed up from the waters of Zeeland. Although she is by far the most famous indigenous goddess of the Netherlands – no fewer than 370 altars, statues and figurines of hers have having emerged – she is virtually unknown. Her name never made it into Dutch national history, or school books. Thankfully in the 1990’s there was a renewed interest in Nehalennia. In this presentation Morgana will be citing some of the research work done and her own observations. Hail Nehallenia!

Who was Nehalennia?

Nehalennia is known from more than 370 votive altars, which were almost all discovered in the Dutch province of Zeeland. (Two altars were also discovered in Cologne, the capital of Germania Inferior.) All of them can be dated to the second and early third centuries CE.

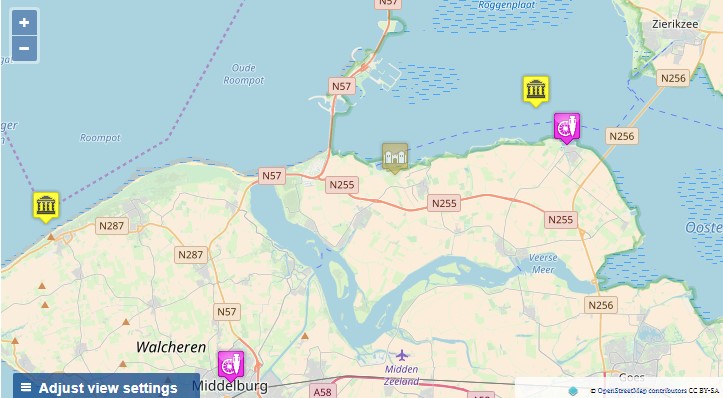

Zeeland certainly has two Nehalennia temples, one was found near Domburg and Colijnsplaat. It is suspected that a third temple was located near Haamstede near Westerschouwen on Schouwen-Duiveland. It is probable that there have been many more sunken temples and have stretched as far as England.

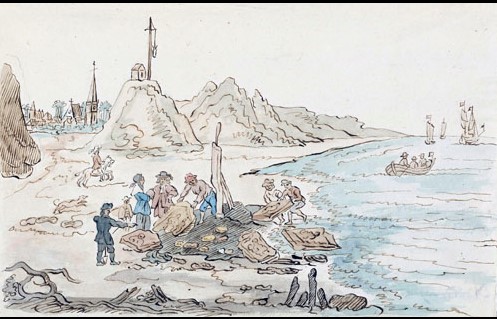

The first temple is located in Roman times directly on the coast near Domburg on Walcheren. There used to be a cove in the high dunes. This was a kind of seaport for the Roman fleet. There was the temple on a high dune in the middle of a kind of forest near a freshwater source. A storm in 1647 exposed the foundations on the beach at Domburg, bordered by tree stumps. Today, the foundations of the temple lie far out to sea and are covered by sand and seawater.

The second temple is located off the coast near the village of Colijnsplaat on Noord-Beveland. Where the water of the current Oosterschelde now flows, there was a Roman village with a river port, called Ganuenta; the village with temple already at the end of the 4th century AD. Which was later swallowed by the Scheldt. It was not until 1971 that a fishing vessel fished out the first altars. After this huge find, there were hundreds of dives.

One had to wait for the Spring tides when the strong current washes away the sand from the temples. Then one has to dive 25 meters deep to find the foundations of the sunken temple.

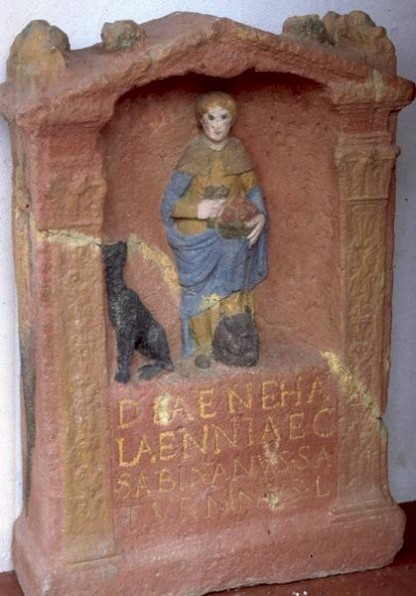

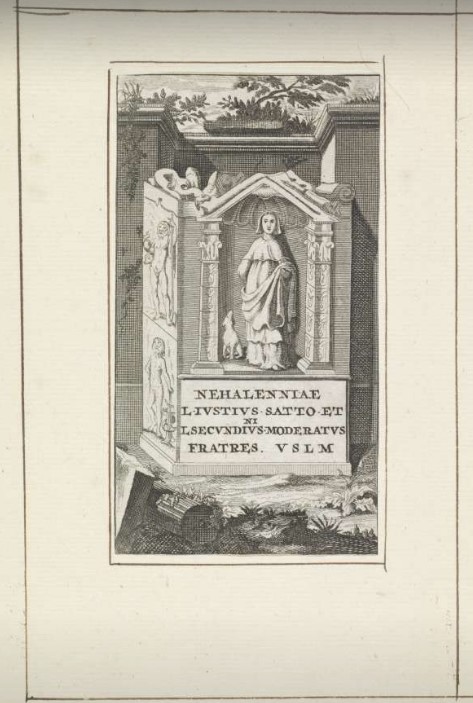

All the donors of the 370 Nehalennia votive altars are men, according to the Latin inscriptions on the altars. On this they have themselves immortalized, always by name and surname. Sometimes they also state their profession, merchandise and origin. They are mainly skippers, shipowners and merchants.

Several inscriptions inform us that the votive altar was placed to show gratitude for a safe passage across the North Sea, and we may assume that other altars were dedicated for the same reason. (Of course, this does not mean that all pieces were erected after a safe passage.) An example of a typical inscription:

To the goddess Nehalennia,

on account of goods duly kept safe,

Marcus Secundinius Silvanus,

trader in pottery with Britain,

fulfilled his vow willingly and deservedly.

Where did the name Nehallenia come from?

The name only became known when the votives were washed up near to Colijnsplaat, January 5, 1647. Other statues were also found depicting amongst others Neptune. This seems to reinforce the idea that this area round Domburg was an important holy site for the Romans. The statues, votives and altars were housed in the Church in Domburg. Unfortunately, many were destroyed in the fire of 1848. Luckily, many sketches of the votives had been made and the inscriptions – in Latin – are quite clear.

According to the most recent theory, the roots are in Welsh. Through Celtic, Nehalennia can be traced back to ‘she who is by the sea’.

According to the theory from Patrizia Bernardo de Stempel (2004), she states that Nehalennia is strongly connected to the sea and that it is therefore possible that her name reflects this fact. In addition, the name Nehalennia always occurs as an addition with a preceding dea, the Latin word for goddess. So it is likely that Nehalennia acts as an extra explanation to dea and tells about the kind of goddess we are dealing with. This suspicion is reinforced by a number of inscriptions where the name appears in the plural, namely deae nehalenniae.

Bernardo de Stempel mainly finds traces in Welsh, with words such as halein ‘salt’ and heli ‘sea’. These words allow for a Late Celtic reconstruction *halen– meaning ‘sea’ which together with a prefix *ne- (meaning ‘on’ and ‘at’) would form the basis for the name Nehalennia. The word formation is then structured as follows; first the prefix *ne- (= by), then the middle part *-halen- (= sea) and finally the suffix *-ja which makes feminine derivations; taken together, the name would then mean “she who is by the sea”.

Annine van der Meer: “Nehalennia has a clear relationship with the water. She stands with one foot on the bow of a ship; when she sits, she sometimes is holding marine parts. This makes her the helmsman, guide and patroness of the skippers who sail from Zeeland across the North Sea. Through the waters there is also a connection to the underworld, with the land of the goddess Helle or Holle, who gave her name to the Hollow Land or Cave Land. Nehalennia also has a connection with the underworld, as evidenced by the symbol of the dog next to her. The symbols prove that Nehalennia has three spheres of influence: the upper world, the earth world and the underworld. This makes her a ‘Mother Goddess’. She is rooted in the earth, in the land of the ancestors. Now she appears to be an ancient and pre-Celtic Mother Goddess from pre-patriotic, yes motherland times.”

In any event it seems as though the name ‘Nehallenia’ is specific to this region.

Annine further writes:

“The visual language of Nehalennia

When you approach Nehalennia from a female perspective, you get an eye for the iconography of the goddess, for her imagery on the altars, which has a deeply symbolic meaning. The Nehalennia iconography even takes on an international allure when you place it in the context of the well-known iconography of the ‘Mother Goddess’. That is quite different from the traditional view that considers ‘mother goddesses’ to be purely local and regional. In this view, the term ‘mother goddess’ is consciously written in lower case according to the convention. These homegrown ‘local’ goddesses rooted in the earth are considered of less importance than the ‘great’ Roman gods such as Jupiter, Neptune and Hercules. The Nehalennia altars show these ‘great’ gods as ‘partners’ of Nehalennia; they are common in the side panels and not in the foreground.

The visual language proves that Nehalennia has three spheres of influence. She is seated on a throne set up on a platform. Above her head there is the shell-shaped canopy. These are symbols of the upper world. In the terrestrial middle world she rules the life-giving force of nature and fertility. Numerous vegetation symbols serve this purpose. She always has a basket of fruits in her left hand. In her right hand she can hold a bunch of wheat stalks, vegetables or even a long steering oar or tiller. She is the helmsman who brings the ship safely across the waters. There are other symbols for the underworld. Near her left foot is almost always a large basket of apples, possibly pomegranates, the fruits of the underworld. At her right foot is her faithful companion: the dog that often looks up to her. Together with this animal she guides the souls of the deceased across the waters of the afterlife to the other world. She gives birth to them in a new life and thus shows herself to be a real Mother who, even in a life after death, takes care of her children.

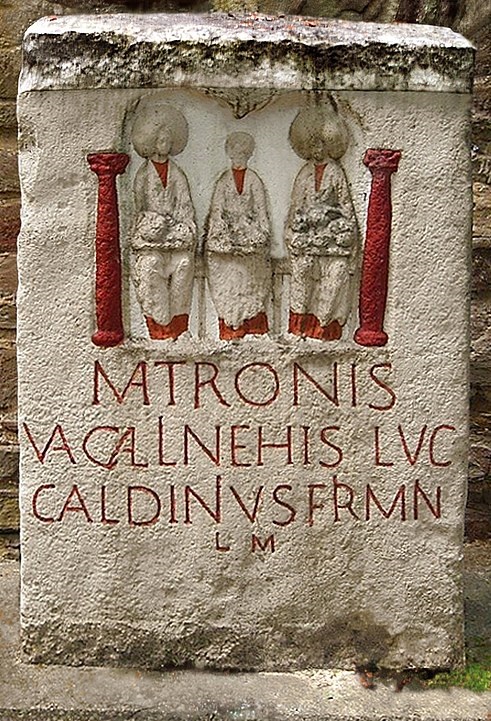

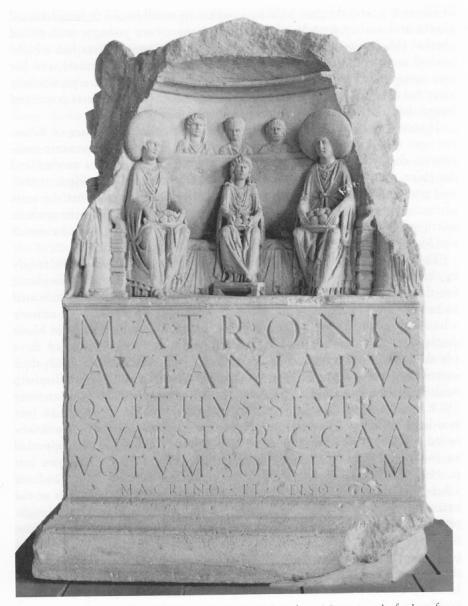

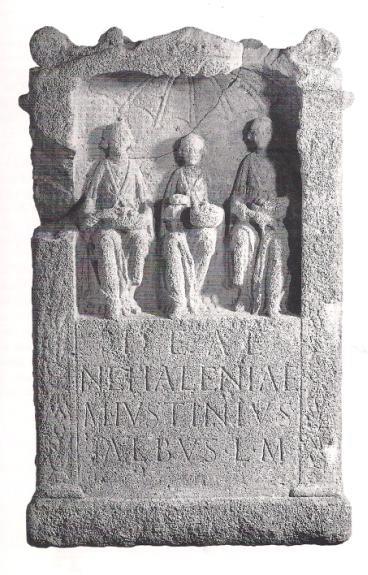

Nehalennia appears on two altar stones in triplicate. In this she shows great resemblance to altar stones of three Mother Goddesses from Germany. They appear on no fewer than 850 altar stones. They are called the “Matrons” in Germany. There is a clear relationship between the triple Nehalennia or the three Nehalennias from Zeeland and the ‘Three Ladies from Germany’.

On the Matrons altar you see a young girl or the Virgin sitting in the middle with loose hair that falls into a part: she represents the earth or the middle world. To her left is her Mother with a large balloon-shaped hat: she represents the sun or the upper world. To her right is her Grandmother, wearing the same balloon-shaped large hat, who represents the moon or the underworld.

What does this trinity mean? First, the goddesses symbolize the connection between the upper, middle and lower world, between sun, earth and moon. Secondly, the trinity can also indicate the changing of the terrestrial seasons in spring, summer, winter-new spring. Always the three goddesses symbolize the relationship between create-maintain-transform.

Foto: Mediatus, 30. Juni 2010, Wikimedia CC

Nehalennia and ‘The Three Ladies from Germany’

It is useful to connect ‘The Three Ladies from Germany’ with Nehalennia because they are all Mother Goddesses. This puts Nehalennia in a broader perspective; it grows above the local and regional framework of Zeeland. In the triangle of the German cities of Cologne, Bonn and Trier with the German Eifel at the heart of this triangle, as mentioned, 850 altars have been found dedicated to the Matrons so popular here. In contrast to the situation in Zeeland, ten percent of these was donated by a woman.

A third of the Matron altars bear the names of independent women, married couples and extended families. This is different with Nehalennia; on her altars you will find only the names of male donors. So precious altars have indeed been offered by women to Mother Goddesses outside Zeeland.

Who are the Matrons?

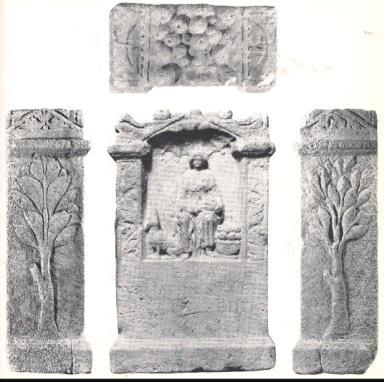

They are initially clan mothers of their own extended families. They are later deified into goddesses. As many as 100 honorary or nicknames related to local clan names were found on the inscriptions. In these clan names there is a clear connection with nature: the names that have to do with the water, the tree and the cow are the most common. Research in Germany at excavated Matron centres shows conclusively that the oldest Matron shrines are tree shrines that often lie next to flowing or standing water.

The visual language on the altars with many trees and branches also proves this. On the Matron altars, sacrificial servants and servants often stand with baskets full of fruit in front of tree shrines. These open-air shrines were not converted into stone temples with walls around them until later in Roman times. Only then are numerous sage altars offered. The Matrons are therefore clearly of pre-Roman origin.

Among the symbols on the altars, the following symbols are common: the tree of life, the fruits of the tree of life, the horn of plenty filled with fruits from the tree of life, and finally the serpent coiling around the tree of life. This applies to both the Nehalennia altars from Zeeland and the Matron altars from Germany. This symbolism indicates a paradisiacal situation of abundance provided by the goddesses. The old man experiences a great connection with nature. Hence, these people set up holy places or power places in the open air as places of gathering.

Among the symbols on the altars, the following symbols are common: the tree of life, the fruits of the tree of life, the horn of plenty filled with fruits from the tree of life, and finally the serpent coiling around the tree of life. This applies to both the Nehalennia altars from Zeeland and the Matron altars from Germany. This symbolism indicates a paradisiacal situation of abundance provided by the goddesses. The old man experiences a great connection with nature. Hence, these people set up holy places or power places in the open air as places of gathering.

Prior to the Roman period, Mother Goddesses are worshiped in the open air in the form of a tree or a wooden statue made from a sacred tree. You will find the shrines near springs welling up from the earth, fast-flowing rivers, as well as standing water near swamps. In particular, waters that well up from the earth, such as springs and subterranean rivers in caves, are experienced as very beneficial and fertile. In the perception of the ancients, they well up directly from the sacred subterranean world, the underworld, where the souls of the deceased reside.

The ordinary women with sacrifices in kind

Women are known to offer in-kind products at temples. How do they get them? Well, they grow it themselves. The connection between women and the plant world is ancient. In the Ice Age, women collected food and gathered as much as 80 to 90% of the daily menu. This elicits the statement that it is better to speak of a gatherer-hunter culture rather than the other way around. After the Ice Age, women develop the first gardens and small fields in the transition from hunting and food-gathering to agriculture. Therefore, traditionally it is women who are engaged in gardening, agriculture and livestock; the men hunt and fish or trade, also in Roman Zeeland. The sea-going vessels must be supplied with foodstuffs, such as grain, dried meat and fruits. This supply is provided by the hinterland.

The Roman armies on the Rhine frontier and also in northern England need grain. There is evidence that in Zeeland from the 1st century AD, a new higher quality cultivated wheat has been harvested. That is why this new type is probably proudly depicted on the altars. Sometimes Nehalennia holds a bunch of grains or wheat in her right hand next to a basket of fruits in her left. Women’s work!

Bread offerings.

The Nehalennia altars have a flat top on which are carved stone offerings, which last forever and do not perish. On top are apples and pears. Once you see a half sun with great outgoing rays, a bread offering. Bones of sacrificial animals are also depicted; baking their moulds into bread prevented the animals from having to be physically killed. Bread in this form is still baked north of Amsterdam as ‘Duivekater’. Probably the women before Nehalennia, as everywhere else, baked sacred bread in certain baking tins. Then they ate their baked goods together during a sacred meal and thus became one with the goddess. And home-made bread offerings are – in view of the baking tins that are found everywhere – a popular and cheap women’s offering internationally.

Women offer small sacrificial statues

In addition to 330 (parts of) altars, five small terracotta figurines or statuettes have surfaced in Ganuenta, a Roman settlement near to present day Colijnsplaat. Offering a small statuette is much, much cheaper than donating a large altar stone. The figurines are often made in workshops near temples. It has been estimated that the workshops in Central Gaul and Germany alone produced between 500,000 and 1 million figurines in the first three centuries of our era. A Matron researcher in Germany stated that at least 50% of goddesses with maternal or fertility properties exists. In the international context with the great majority of local female deities and their sacrificed art, this estimate seems on the meagre side.

In Germany, research has been done on 1000 statues in which places the small female statues have been found; of 70% it was possible to trace the location. About 33.5% has been found in temples or subterranean storage rooms of temples; 15.7% in houses and 14.9% in graves.

For the Netherlands it has been established that among the small terracotta statues and altarpieces the female deities are in the majority. It is here that the invisible women emerge, in large numbers. Women bond with their ‘local’ goddesses, seek their support and have sacrificed to them.

The temples and the temple staff

What the sea took in the Netherlands has been rediscovered in Germany. At least ten sizable Matron Centres have been excavated here. The Matron Sanctuary on top of Mount Addig in Germany’s Eifel is located in an ancient forest; the mountain is surrounded by three streams. It is the sacred centre of the Celtic clan of the Vacalli or cowherds who inhabit the area around it. In this great sanctuary, which is called the ‘Pompeii of the Eifel’, the first large garden with the sacred tree appears. Later in Roman times a temple for the three Matrons was built there; in the temple there must have been a larger cult statue. There is also a common storage area for the grain. Finally, there is a collection house for clan. Processions are held in the covered pedestrian alley that surrounds the complex, so that the procession can continue in bad weather. Communal meals are also held after sacrifices have been made. Benches and podiums have been found that indicate that the assembly halls also had a theatrical function. Incubation rituals may also have taken place. People were cured through dreams or received clues to certain problems through visionary dreams. It is very likely that in these centres, where traditionally later deified clan mothers are worshiped in ceremonial clothing, their female progeny also serves. On the altars, the ladies wear the same ceremonial clothing as their deified Matron foremothers. These ladies are more than mere wives of the gentlemen sacrificer’s. Some are depicted alone with their top round hats while sacrificing. They can therefore be priestesses.

Prophesying and shamanizing.

Of the 834 Matron inscriptions on pointers, 116 have been found that contain a revelation inscription. The stones were donated by the donors after the goddesses revealed themselves in a vision or in a dream. This indicates direct contact between the goddesses and their followers.

Three revelation inscriptions have also been found on the 370 keys of Nehalennia that have been recovered. Altars of twelve early Germanic goddesses have been found that stood in open-air sanctuaries. Jan de Vries and Kees Samplonius assume that all these twelve goddesses from Dutch soil were oracled. Prophecy and oracles have traditionally been a specialism of women, of ‘wise women’. It is certain that both the Celts, the Romans like the Teutons had respect for the prophetic and healing gifts of wise women. Their influence was great because with their visionary powers they helped the people and healed them. Also in the temples of Nehalennia in her aspect of goddess of the underworld, priestesses who represent her must have argued: it is a new and for me unexpected aspect that finally resurfaces with Nehalennia. We have rediscovered the Pythias from our own soil.”

(NB – for the text in Dutch see references)

The temple… A modern reconstruction

The Nehalennia Temple has been reconstructed after an example from the time of the Romans and the Celts. The copy is located on the banks of the Oosterschelde National Park in the Zeeland village of Colijnsplaat. This historic monument is a replica of a sanctuary that stood in that area between 150 and 250 AD. At the time, it was much visited by traders from north western Europe. The building is intended as a tangible sign of a past completely forgotten up to half a century ago. Since its opening in 2005, the Nehalennia temple has grown into a tourist attraction in Noord-Beveland and a well-known icon in Zeeland. The replica has gained widespread recognition as the second window in the official canon of Zeeland. In addition, for many visitors the temple is a special place for contemplation and spirituality.

The Nehallenia Temple has been incorporated in the Canon of Zeeland.

Reconstruction of the temple, Colijnsplaat / Reconstructie van de tempel op Colijnsplaat

During the 1970’s more artefacts were found. However only wood and roof tiles were found but no pillars / columns. With only wood for supports this would be the general construction:

Also from Mikko Kriek: a painting of how the Roman harbour of Ganuenta (180-230 AD) could have looked like.

Building the temple

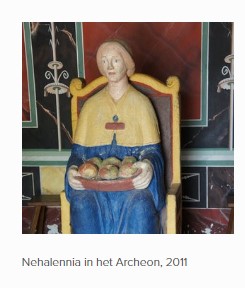

The temple building was commissioned by the Nehalennia foundation and designed by architect Henk Zandee. Archaeological draftsman Harry Burgers of the Free University of Amsterdam provided information about Roman architecture and Celtic geometry. It was realized under the supervision of client Jan Rolloos. Pupils from the school community Nehalennia in Middelburg have made the beautiful oak roof in a traditional and traditional way under the guidance of teacher Wim Mulder. Colleague Bram Slabbekoorn installed the electricity. In addition, the school community donated a successful modern version of a statue of the goddess, made by teacher Hans Zuidema. This is placed against the left inner wall.

(Nehalennia in bronze. Guido Metsers 1989 – many people sit next to her on the bench and have their photo taken. )

In the Themepark Archeon, there is a reconstructed Roman temple – based on one from Cuijk – near the roman town of Novio Magus, modern day Nijmegen. This temple is currently used for parties, especially Wedding Feasts, and often called the ‘Nehallenia Temple’.

In 2019 I visited the amazing Gallo-Roman temple in the district of Metzenberg. municipality of Tawern, near to Trier. It was built in the 1st century AD at about the same time as the Nehallenia temples.

Here are some of the photos I took.

The names of the persons who gifted the statues and altars to Nehallenia show they were merchants from Italy, Cologne, Trier and Britannia. They traded in salt, fish sauce and textiles. Other wares were ceramics from the area around the Rhine, terracotta figurines from Cologne and Trier, and wine from Southern France and the Mosel-area. One inscription found translates to: “Before Nehalennia, Marcus Exingius Agricola, citizen of Trier, salt merchant in Cologne, has fulfilled his promise, willing and with reason”.

The temple is dedicated to Mercury, God of trade, so it would be reasonable to think there was a link with this temple and that of Nehallenia. There is a modern statue of Mercury, complete with various attributes, now in the temple.

Trier was a Roman town founded in the 1st Century AD and is situated on the River Moselle, which flows into the River Rhine at Koblenz. The Rhine flows further into the Netherlands and is one of the big rivers forming the Delta in the West of the country.

The temple was also dedicated to Epona who “was a protector of horses, ponies, donkeys, and mules. She was particularly a goddess of fertility, as shown by her attributes of a patera, cornucopia, ears of grain and the presence of foals in some sculptures. She and her horses might also have been leaders of the soul in the after-life ride, with parallels in Rhiannon of the Mabinogion. The worship of Epona, ’the sole Celtic divinity ultimately worshipped in Rome itself’, as the patroness of cavalry, was widespread in the Roman Empire between the first and third centuries AD; this is unusual for a Celtic deity, most of whom were associated with specific localities”.

Also Apollo as well as Isis-Serapis were worshipped there.

(Gallo -Roman temple at Tawern, near to Trier – Augusta Treverorum , Germania Superior) – photo Morgana

Travelling along the Rhine into Germania Inferior (now modern day Netherlands) merchants on their way to Brittania could have easily visited the Nehallenia temple.

Nehallenia revered today

In recent years Nehallenia, Goddess of the Lowlands, has been rediscovered. Although the modern temple at Colijnsplaat was not designed as a ‘working temple’ it does attract devotees who make the pilgrimage there.

Marjolein Makes on revisiting Colijnsplaat in September 2017. “So, on Mabon of that same year, we made the trek again. This time it was clear. I could feel the pull of the sea, connect to the land and the past in a way I never could before. Had experiences with other pagans and witches that I felt deeper within me than many before that. There was a feeling of ancientness, of primal and wildness, that I had been seeking my entire path, but hadn’t been able to find. I found it there. I found it with Nehalennia.”

A modern devotion; Nehalennia statue at the harvest festival Marjolein Makes.

A modern devotion; Nehalennia statue at the harvest festival Marjolein Makes.

References

“Onbekend maakt onbemind – Nehalennia van Zeeland en de onzichtbare vrouwen om haar heen.”

- Annine van der Meer, February 2016, reworked September 2016.

Dr Annine E. G. van der Meer is a historian of religion, theologian and symbol expert. She wrote a number of authoritative books about forgotten women from women’s history, www.anninevandermeer.nl

I am indebted to Annine for this essay which I have used extensively here in an English version.

For the Dutch version:

Dr. Annine E.G. van der Meer, ‘Nieuw licht op Nehallenia’: Nederlands, Paperback ISBN 9789082031324, Druk: 1, maart 2015 See the review.

Nehallenia Godin van de zeekust: Gardenstone – Nederlands https://boudicca.de/ See the review.

(links all accessed July 2021)

Meaning of the name Nehallenia: https://www.nemokennislink.nl/publicaties/het-raadsel-van-nehalennia-ontrafeld/

Nehallenia: https://www.livius.org/articles/religion/nehalennia/

For clearer images go to: https://www.livius.org/pictures/netherlands/colijnsplaat/votive-to-nehalennia-4/

Nehallenia-altaar met staande Nehalennia en haar hond, anonymus 1715

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/RP-P-OB-75.164

Drawing: The discovery of a Nehalennia temple in Domburg. 19th Century drawing after a sketch from 1647) https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehalennia_(godin)#/media/Bestand:Nehalennia_Domburg.jpg

Reconstructie van de tempel op Colijnsplaat: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehalennia_(godin)#/media/Bestand:Tempel_van_Nehalennia_Colijnsplaat_(2).JPG

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehalennia_(godin)#/media/Bestand:Nehalennia_Domburg.jpg

Nehalennia in brons, Guido Metsers 1989 : https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guido_Metsers

Archeon, reconstructed Roman temple, from Cuijk:

https://leukefeesten.nl/feestlocatie/alphen-aan-den-rijn/archeon/#&gid=1&pid=1

Matronensteen: https://vici.org/vici/16496/

BLOG: NEHALENNIA, EEN ZEEUWSE GODIN

Image of the Goddess, limestone 82 cms/ Beeld van de godin, kalksteen, 82 cm. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden Leiden

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nehalennia_(godin)#/media/Bestand:Leiden-Nehalennia-statue.JPG

A modern interpretation; Nehalennia statue at the harvest festival:

https://marjolijnmakes.com/2021/01/10/finding-nehalennia/ .

Zo erg goed. Nehellenia, special uit Zeeland –> Leiden (RMO).

Bedankt Niek.. afgelopen week was ik ook in TONGEREN, België en daar kwam ik ‘de Matronae’ weer tegen.