Religions and Myths – gods & goddesses

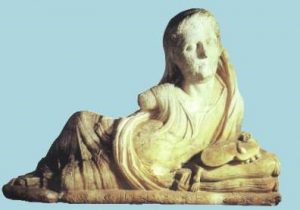

(Etruscan deities, Etruscan Museum, Volterra)

Of Gods and Goddesses and mythical beings, Nancy Thomson de Grummond writes in the introduction to the book “The Religion of the Etruscans”:

“Unfortunately, we know so little of these writings and teachings that we are unable to discern what, if any, may have been their theological concerns or what debates may have enlivened their encounters. Further, it is a perennial frustration in studies of Etruscan religion that little about Etruscan prophetic or priestly texts can be confidently traced back earlier than the first century BCE, when in fact Etruscan civilization had become fully submerged in the dominant Roman culture.” (de Grummond)

Perhaps it is true that there aren’t many texts available there is certainly enough evidence of Etruscan deities. In his book “Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition” (1892) Charles Godfrey Leland describes a number of gods and goddesses. The complete text of this book can be found on Sacred Texts. Com. As a way of introduction, we read:

“This is essentially an ethnography of what neopagans term a ‘family tradition’: that is, practical magic–but with an Italian flavour. We meet the Goddess of Truffles, learn the details of divining by oil, fire and molten lead; how to bring back the dead, and coerce nature spirits into performing favours. Leland carefully documents his field notes, and includes the full text of numerous spells and songs in Italian, particularly the Tuscan dialect. The text includes many fairy-tales of the sort that are not suitable for children. Leland draws on often obscure sources which tie his data into classical and pre-classical pagan traditions, particularly the little-known Etruscan religion.”

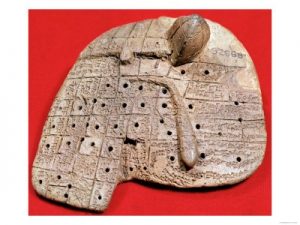

Also, as we shall see later names of deities were included on the Liver augury models such as the Liver of Piacenza. But first for this presentation, however, I would like to highlight one of the goddesses Leland mentions and is of particular interest, I think, for us as witches. Her name was Feronia

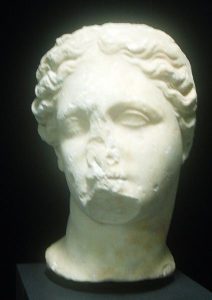

(Head of Feronia archaeologic museum of Rieti, Italy. From Punta di Leano, Terracina dated last quarter of II century BC)

Feronia was the Etruscan Goddess of Fire & Fertility. She was also the protectress of freed slaves and Goddess of the Underworld. For this reason, she was particularly popular with plebeians or the lower classes, the poor and travellers. November 13, is her festival, the Feroniae.

Leland writes: “Feronia was an old woman who went about begging in the country, yet she always had a gran pulitica–that is, she was intelligent or shrewd or very cunning in manners–and, as one would have believed, she was a witch. All who gave her alms were very fortunate, and their affairs prospered. And if people could give her nothing because of their poverty, when they returned home after the sun rose (dopo chiaro) they found abundant gifts–enough to support all the family–so that henceforth all went well with them; but if any who were rich gave her nothing, and had evil hearts, she cursed them thus; —

“‘Siate maledetti

Da me che vi maladisco

Di vero cuore!

E cosi i vostr ‘affari

Possono andare

A rotto di collo

Fame e malattie

Cosi non avrete,

Non avrete piu bene!’

(“‘Be ye all accursed

By me who curse you

With my heart and soul

May your lives for ever

Go to utter ruin;

Illness and starvation

Be ever in your dwelling!’)

By this, they knew she was a witch. But when she was dead she became terrible and did much harm. However, when those who had wronged her, and knew it, went to her tomb and begged pardon they were always sure to obtain it.”

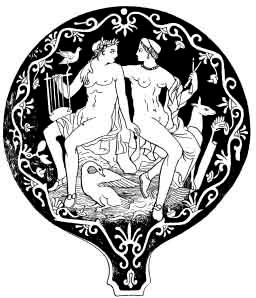

I should also mention that as far as forms of worship and magical tools the Etruscans were very fond of mirrors and they often depicted deities and included their names. The mirrors recorded the myths and tales of deities. “More than 3000 such mirrors have been unearthed from Etruscan archaeological sites and dot museum collections around the world. The earliest, dating from the sixth century BC, exhibit scenes from Greek mythology, frequently featuring Aphrodite, goddess of beauty, love, and procreation. As the Etruscan civilisationevolved, the people adopted Greek mythological figures as their own, and Aphrodite became Turan, goddess of love, sex, and fertility. She’s depicted on the mirrors as a beautiful woman, often naked or naked to the waist, with cascading ringlets. When clothed, she wears Greek-style garments with many jewels, and often a tiara. Occasionally, she’s winged.

(http://noveladventurers.blogspot.nl/2013/04/turan-goddess-of-love.html) Patricia Winton

Larissa Bonfante writes: “Etruscan mirrors and wall paintings constitute a rich repertoire of Etruscan mythological scenes. Often the labels on the figures give us an insight into points of view of images, themes, and motifs that are either strictly Etruscan or differ in significant ways from Greek religious and mythological iconography. The following appear to be characteristically Etruscan: (1) the prevalence of couples and ‘‘dyads,’’ (2) the importance of mothers, (3) representations of scenes of the birth of gods, with related midwives and other medical subject matter, and (4) the frequent appearance of souls or ghosts.” In this sense the mirrors seem to have a divinatory function but also for carrying out magical acts. And certainly, not used in the way we would use mirrors today. “From the numerous scenes of prophecy that appear on Etruscan mirrors, it may be conjectured that the mirror itself was an instrument of prophecy, as in the examples of katoptromanteia (conjuring with mirrors) attested in Greek and Roman ritual. Rather like making predictions by gazing in a crystal ball or a vessel filled with liquid (lekanomanteia), one could discern the future by looking at a reflected but somewhat mysterious image in the shiny surface of the mirror.

Several Etruscan mirrors show a female figure gazing intently into a mirror, seemingly not in the act of grooming but rather as a part of conjuring with mirrors/katoptromanteia” (NancyThomson de Grummond) “Sometimes the names of the figures are inscribed making the mirrors important for knowledge of the Etruscan alphabet and writing.” (Judith Swaddling for the British Museum, commenting on the CSE project)

(Engraved mirror: The diviner ‘Chalkas’ (Vulci ca 400 BCE, Vatican Museo Gregoriano Etrusco)

Divination/ Haruspicy; liver augury

In the “Chalkas” mirror we can see the diviner standing “with one foot on the rocky earth and gesturing with the right hand … as in siting of temples, orientation by cardinal points was crucial to the process; the universe was full of gods prepared to communicate with the devout, and the liver was its microcosm.

The haruspex interpreted a variety of omens, from lightning and monsters to the entrails of victims.” (Turfu and Gettys) They were mediators between gods and men.

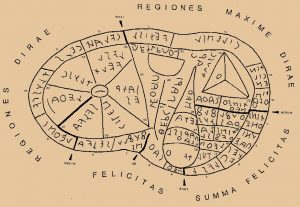

“The Piacenza Liver (a representation of a sheep’s liver cast in bronze for use in haruspicy) is deliberately sectioned off with lines indicating the domains of individual gods with specific names. This demonstrates lucidly the established order of Etruscan cosmos which this hepatic microcosm served to represent. What’s more, the Piacenza Liver is known to be preceded by a similar Babylonian model in clay made a millennium earlier. There is no shred of doubt that their set of divinatory beliefs are related and we also know that the Babylonian pantheon is rich and complex too. Hopefully then we can shed this insidious myth that Etruscan religion and pantheon have no native structure to study. They certainly do.”

http://paleoglot.blogspot.nl/2007_02_01_archive.html

(Diagram of the sheep’s liver found at Picenum with Etruscan inscriptions on the bronze sheep’s Liver of Piacenza)

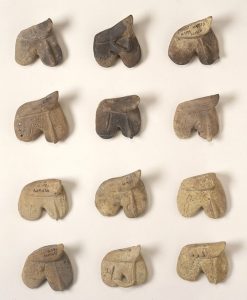

Examples of clay models found in Babylon:

Babylonian liver augury: http://imagesource.allposters.com/IMAGES/BRGPOD/68838.jpg

Several examples of Mesopotamian liver models:

Figure 2. Liver Models from Mari – Musée du Louvre – Paris – AO 19829, AO 19830, AO 19831, AO 19832, AO 19833, AO 19834, AO 19835, AO 19836, AO 19837, AO 19838, AO 19839, AO 19840 (Image Copyright: C. Larrieu). http://www.theposthole.org/read/article/277

[Louvre] Palace of Mari These inscribed models are part of a cache of 32 livers discovered in room 108 of the Palace. The liver was considered in Mesopotamia the essential organ for the thought and the feelings. The examination of entrails of a sheep or a kid was used to predict the future. Malformation or anomalies of the liver were reproduced in clay and the prediction was inscribed. These copies of the livers served as a reference for the priests and demonstration pieces for students 1. Prediction of Kish concerning Sargon 2. Prediction of imprisonment 3. The country will revolt against Ibbi-Sin (last king of the 3rd dynasty of Ur), the liver was correct 4. Prediction of the destruction of a small city

http://www.wiglaf.org/~aaronm/travel/paris2009/Louvre/tn/Liver%20models%20for%20divination.jpg.html

(Figure 4. Assyrian diviner extracting the entrails from a sacrificial animal (bottom left corner) – Assurnasirpal II’s) http://www.theposthole.org/read/article/277

In the essay “Dialoguing with the Gods: the Liver Models from Mari” Emilio Passera describes in detail how the models were used.

“The Mari models are strongly linked with religion, which in ancient Mesopotamia had different contexts, ranging from state to private, but hepatoscopy was used in both contexts. We know in fact that it was used for state concerns, but in Mari, we also have more common requests, such as if a man should buy a boy as a slave or not. Hepatoscopy shows that the relationship with the gods was a dialogue, where the diviner asked them to show their will in order to act in the most profitable way (Heeßel 2010). Omens in general show us how the future was conceived; differently from the unchangeable destiny of the Romans, in Mesopotamia the very purpose of divination was to be able to act against future threats, and know the will of the gods. Living in harmony with them was beneficial, and thus extispicy was strongly connected with decision-making, especially in state affairs. This is especially true for the Neo-Assyrian Empire where the abundance of evidence shows how divination played a key role in influencing the king’s actions: nothing could be done against a bad omen but postpone the planned project and try again after a reasonable amount of time had passed (Koch 2011). This again stresses how there was little division, if any, between the king, the state, and religion. They were strongly linked together, as the king, as the state, asked the gods an opinion on decisions. During the Neo-Assyrian period in particular, we see how astrology and extispicy played a complementary role, but while astrology was highly debated and various interpretations were given, extispicy was straightforward and diviners never offered more interpretations. Divination was so important that diviners followed the army on expeditions (Koch 2011; Figure 4)”

It was this aspect that we see so evident in the Etruscan form of divination. Whether via Liver Augury or the Mirrors – their fate was intrinsically linked to the ‘messages of the Gods’.

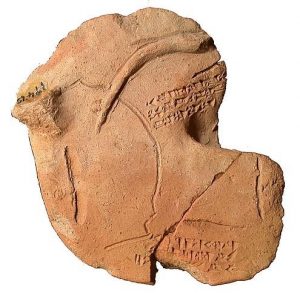

Also, the Hittites used Haruspicy in this way:

The following passage from the prayer of Kantuzili, a prominent Hittite priest of the first half of the 14th century, presents the function of divination quite clearly.

Liver model (2nd half of 16th or 1st half of 15th cent. B.C.)

“Now may my god open his innermost soul to me with all his heart, and may he tell me my sins so that I can acknowledge them. May my god either speak to me in a dream — and may my god open his heart and tell me my sins so that I can acknowledge them — or let a dream interpretess speak to me or let a diviner of the Sun-god speak to me by reading from a liver in extispicy, and may my god open to me with all his heart his innermost soul, and may he tell me my sins so that I can acknowledge them.”

http://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/HPM/hpm-en.php?p=divin-en

But how did the haruspex divine or read the liver?

This is a diagram of the partitions from the Liver of Piacenza:

According to Natalie L.C. Stevens in “A New Reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven”:

“THE EVIDENCE According to ancient authors, the Etruscans divided the heaven into 16 equally sized regions, each of 22,5 degrees, called paries, regiones, or sedes, the dwelling places of gods. Such a 16-part heaven was unique in the ancient world; the Romans, for example, knew only a four-part heaven. According to Cicero and Pliny, the Etruscans twice duplicated the more common quadri-partition to create this 16-part heaven. It is not known when the Etruscans created the 16-part division, but the quadri-partition was already known in the seventh century B.C.E.4

Haruspices (seers) used the heavenly partitions to read the will of the gods by noting, for example, the direction of lightning. The eastern paries-were favourable and the western unfavourable. Therefore, the north south line was of fundamental importance. That Tin, the main god of lightning, dwelled in the north may be inferred because lightning in the north-western part was seen as most terrible and in the north-eastern part was most lucky. The south-east was less lucky and the south-west less terrible. This four-part division in the omens strongly suggests that quadri-partition was the original core of the 16-part heaven.”

(The Urn of Av Lecu, Etruscan museum, Volterra)

A modern interpretation.

In 2012 I was very fortunate to be involved as a participant in a ritual based on the Etruscan “Liver Augury”. I was curious as to how Edith Cammenga and her Dutch team prepared for it so recently I visited her and interviewed her.

My first question was why did they use a sheep’s liver? Edith told me that sheep (and goats) were very common in the ancient world. Their gut and liver was often full of parasites which would reflect the state of the local area where they grazed. Was it fertile? Or suffered from drought? Or other disasters? Did the gods need to be appeased?

When the sheep was sacrificed, there was a membrane surrounding the liver. The haruspex would look at the condition of the liver through the membrane, not even removing it from the sheep. They could see immediately how the land was. Was the liver bright red or spotted with white blemishes?

She continued…” The ‘caput’ (literally head) was very important. Discoloration would be considered a very bad omen.”

In the ritual we did – a fresh sheep’s liver was used. We also became the gods in the ‘model’ as described in the Liver of Piacenza. The names of the Gods were written on our bodies, with body paint, and we were placed in the particular partition according to the God. During the ritual, we were asked to guard our section and in so doing we became the oracle. One of the reasons I asked Edith about the ritual was because I realised I couldn’t recall what I said or did. She told me that people moved around the ‘model’ whilst others from the ritual team acted as guardians/watchers. The only thing I could distinctly remember was a friend of mine being told that she would not go to Egypt. As it turned out her plans to go to Egypt didn’t manifest.

The thing that made the most impression on me was, in fact, the connection ‘with the land’. At one point, we all looked at the liver. It is quite different, of course, actually looking (and feeling) at the liver than seeing photos or looking at the bronze/clay models. Regarding the names of the gods and spirits, and the regions or partitions, as noted earlier (Natalie L.C. Stevens) the North-Western part was the most dreaded whilst the North-East the most fortunate.

I later looked at the names of the Etruscan Deities the equivalent (if any) with the Greek and Roman. I also checked back on Leland’s book “Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition”, Charles G. Leland/ 1892.

See appendix 1 and 2 for the names of the Gods.

And https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Etruscan_mythological_figures#L

One of the things which came about after participating in the ritual in 2012, was the growing awareness of how important storm gods and lightning were in the ancient world.

From Wikipedia, we read:

“Tinia, Tina, Tin

Chief Etruscan god, the ruler of the skies, husband of Uni, and father of Hercle, identified with the Greek Zeus and Roman Jupiter well within the Etruscan window of ascendance, as the Etruscan kings built the first temple of Jupiter at Rome. Called apa, “father” in inscriptions (parallel to the -piter in Ju-piter), he has most of the attributes of his Indo-European counterpart, with whom some have postulated a more remote linguistic connection.[42]The name means “day” in Etruscan. He is the god of boundaries and justice. He is depicted as a young, bearded male, seated or standing at the center of the scene, grasping a stock of thunderbolts. According to Latin literature, the bolts are of three types: for warning, good or bad interventions, and drastic catastrophes.[43] Unlike Zeus, Tin needs the permission of the Dii Consentes (consultant gods) and Dii Involuti (hidden gods) to wield the last two categories. A further epithet, Calusna (of Calu), hints at a connection to wolves or dogs and the underworld.[43] In post-classical Tuscan folklore he became an evil spirit, Tigna, who causes lightning strikes, hail, rain, whirlwinds and mildew. (Includes references from Leland and de Grummond.)

Two years later – in 2014 – I visited Hattusha, Turkey, the ancient capital of the Hittites, where I would find many instances of storm gods. I was also delighted to find out that the Hittites also used clay ‘models’ of livers and knew this form of divination. 🙂

To conclude, whilst we may not know much of Etruscan language, their influence on Roman culture and our ‘western’ culture is undeniable. A visit to modern day Tuscany is certainly recommended!

Many thanks too to Edith Cammenga and Yuri Robbers who pointed me in the right direction for source material. And of course, for the wonderful ritual experience in 2012!

Volterra today… (Volterra, Morgana, August 2016)

****

Appendix 1: The Gods Present on the Liver of Piacenza, by Region

Region 1: tin/cil/en(s) (Jupiter; Nocturnus [god of the night]).

Region 2: tin/thvf (Jupiter; Thufltha [unknown goddess]).

Region 3: tins/th ne(thuns) (Neptune in the region of Jupiter).

Region 4: uni/mae (Juno;Jupiter?).

Region 5: tec/vm (Apollo-like god).

Region 6: Ivsl (of Lynsa Silvestris [unknown goddess]).

Region 7: neth(uns) (Neptune).

Region 8: cath(a) (sun-related goddess).

Region 9: fuflu/ns (Liber [Bacchus, Dionysos]).

Region 10: selva(ns) (Silvanus Veris Fructus).

Region 11: lethns (Lethams [unknown god]).

Region 12: tluscv (unknown god).

Region 13: eels (of Earth).

Region 14: cvl(su) alp(an}) (door-keepingunderworld goddess [Alpan? a term, goddess, or personification of Harmony?]).

Region 15: vetisl (of Veiovis).

Region 16: cilensl (of the god of the night).

Region 17: tul(ar) (“boundary”).

Region 18: lethn (Lethams [unknown god]).

Region 19: la/si (of Lasa [Etruscan goddess in the circle of Turan; Venus]).

Region 20: tins/thvf(ltha) (Thufltha [unknown god dess] of Jupiter).

48 Dating to 300-250 B.C.E. (Cristofani 1989-1990, no. 69). 49 Dating to the Hellenistic period (Cristofani 1989-1990, 349, nos. 70,71). 50 For Rath, see Maggiani 2002, 167-68, no. 5 (fourth or the beginning

(From “A New Reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven” Author(s): Natalie L. C. Stevens Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 113, No. 2 (Apr., 2009), pp. 153-164 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America

***

Appendix 2

From, THE RELIGION OF THE ETRUSCANS – Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon, Editors University of Texas Press Austin chart 1. A Selected List of Etruscan Deities and Their Greek and Roman Comparisons

Listed below are some of the principal deities of the Etruscans within their spheres of influence. The spelling of their names varies in Etruscan inscriptions, and some of the major variants are supplied here, but it is not possible to include all of them. A word of caution is also in order regarding the equations with gods from Greece and Rome. Rarely is any Etruscan deity exactly equivalent to a Greek or Roman divinity, and it is best to think of these non-Etruscan mythological figures only as comparisons and in general to use Etruscan forms of the name to avoid making unwarranted assumptions.

NB I added the extra column “Charles G. Leland” using his book “Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition” (1892) as reference, http://www.sacred-texts.com/pag/err/index.htm

Etruscan Greek Roman Charles G. Leland/ 1892

‘ Olympian’’ Deities

Aplu, Apulu Apollon Apollo Aplu/ ch 1

Artumes, Aritimi Artemis Diana

Fufluns, Pacha Dionysos Bacchus Fuflunus / Fuflunu/ Faflon/ ch 4

Laran Ares Mars Maso/ ch 2

Mariś — Genius? Mania? / Mania della notte/ ch 2

Menrva, Menerva Athena Minerva

Nethuns Poseidon Neptunus

Sethlans Hephaistos Vulcanus Sethlans/ Sethano ch 5

Tinia, Tin Zeus Jupiter Tinia/ ch 1 Spulviero / ch 4

Turan Aphrodite Venus Turan/ Turanna/ ch 1

Turms Hermes Mercurius Turms/ Téramó ch 1

Turnu Eros Cupid, Amor Cavalletta/ cicada ch 9

Uni Hera Juno Cupra / ch 10

Vei Ceres? Demeter?

Silvanio/ Silvanus/Faunus/ ch 3

Cosmic Deities

Catha, Kavtha, Cath — Solis filia

Cel Gaia Terra Mater

Culśanś — Janus

Thesan Eos Aurora

Tivr, Tiur Selene? Luna?

Usil Helios Sol

‘‘Hero Gods’’

Hercle Herakles Hercules

Tinas Cliniiar (Cliniar), Dioskouroi, Dioscuri,

or Castur or Kastor and or Castor

and Pultuce Polydeukes and Pollux

Underworld Deities and Demons

Aita, Calu Hades Pluto Turms Aitas/ Mercury / ch 1

Charu _? Charon Charun/ ch 8

Phersipnei Persephone Proserpina Feronia/ ch 3 Diana/Herodias ch 8

Hecate Witches& walnuts/ ch10

References

Maps:

- http://www.dirkcannaerts.be/klassiek/etrusken/etrbeelden/map.jpg

- http://www.dirkcannaerts.be/klassiek/etrusken/kaart-etrurie.jpg

- Human Sacrifices and Taboos in Antiquity: Notes On an Etruscan Funerary Urn, Larissa Bonfante

- THE STUDY OF ETRUSCAN RELIGION Nancy Thomson de Grummond

- “The Skill of the Etruscan Haruspex” Jean Macintosh Turfu & Sandra Gettys.

- A New Reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven NATALIE L.C. STEVENS

- Votives, Places and Rituals in Etruscan Religion, Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, Editors S. Versnel, D. Frankfurter, J. Hahn VOLUME 166

- Etruscan Roman Remains in Popular Tradition, Charles G. Leland/ 1892

Sarcophagus and lid with husband and wife, Etruscan, 350–300 B.C., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Credit: Sebastià Giralt via Flickr: http://www.pri.org/stories/2016-04-15/where-did-etruscan-people-come-we-still-dont-know-linguistic-and-genetic-clues

Language: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/phoenician.htm

“The Pyrgi tablets” are laminated sheets of gold both in Etruscan and Phoenician languages. They are exhibited at the Etruscan Museum in Rome – “Museo di Villa Giulia”: http://ancient-time.blogspot.nl/2011/01/ancient-etruscan-art-of-europe.html

(Other really good photos of Etruscan artefacts. Lesley)

Note: The Pyrgi Tablets, found in a 1964 excavation of a sanctuary of ancient Pyrgi on the Tyrrhenian coast of Italy (today the town of Santa Severa), are three golden leaves that record a dedication made around 500 BC by Thefarie Velianas, king of Caere, to the Phoenician goddess ʻAshtaret. Pyrgi was the port of the southern Etruscan town of Caere. Two of the tablets are inscribed in the Etruscan language, the third in Phoenician.[1]

These writings are important in providing both a bilingual text that allows researchers to use knowledge of Phoenician to interpret Etruscan, and evidence of Phoenician or Punic influence in the Western Mediterranean. They may relate to Polybius’s report (Hist. 3,22) of an ancient and almost unintelligible treaty between the Romans and the Carthaginians, which he dated to the consulships of L. Iunius Brutus and L. Tarquinius Collatinus (509 BC).

The tablets are now held at the National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia, Rome.

Max Dashu: Etruscan Women & Social Structure

(Etruscan sarcophagus from Cerveteric, 520 BC Museo Nazionale de Villa Giulia, Rome. Photo by Fraxe 2009)

Head of Feronia, archaeologic museum of Rieti, Italy. From Punta di Leano, Terracina; dated last quarter of II century BC: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Head_of_Feronia_(cropped).jpg

Chalkas mirror with Liver Augury

Turan, Goddess of love by Patricia Winton

Corpus Speculorum Etruscorum NB The Corpus of Etruscan Mirrors/ Corpus Speculorum Etruscorum is a worldwide project to catalogue all known Etruscan mirrors in public and private collections. Under the leadership of the Istituto degli Studi Etruschi ed Italici in Florence, some 30 volumes have so far been produced. The first British Museum volume appeared in 2001

Liver of Piacenza By Lokilech – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Image of Liver of Piacenza as a diagram

“Dialoguing with the Gods: the Liver Models from Mari” Emilio Passera (pdf).