I first met Seti I in Cairo, in a room as quiet as an intake of breath. In the dimmed light, his mummified face—regal, startlingly human—rested behind glass, the mortal trace of a man who stood beneath Nubian suns and ordered stone to remember the gods and sky. Later, on my travels south and crossing to the West Bank at Luxor, I came to the Valleys of the Kings, Queens, and Nobles. Because of safety concerns, Seti’s tomb (KV17) was closed. There had been rockfalls, yet I could peer down into the cool mouth of the corridor into the limestone earth and catch the beginning of the wall inscriptions: the opening passages of the Book of Gates. Even at the threshold, the text worked on me like a tide at the ankles—twelve hours, twelve trials, travelling in the sun-boat, uttering the names you must know to pass.

Seti has long been a companion in my devotions and studies—not only a formidable Nineteenth Dynasty pharaoh, but an exemplar of ritual sovereignty: how a culture understands leadership as both service and keeper of sacred cosmology. My travels to reach his temple centre would demand more than I had expected. To get there, we would travel via Dendera and then on to Abydos, a distance of more than 100 kilometres.

Dendera’s Starry Counterpoint Dendera is the cult centre of Hathor; her temple offers a sense of power and artistry. The famous Zodiac of Dendera, with its Greco-Roman skin and Egyptian bones, is less a toy for horoscopic tinkering than a cosmography—the sacred order by which any witch finds their bearings. On a day when the temple was near empty, I stood in the inner sanctuaries and heard the Dendera hush and a weeping for the loss of the celebrated circular sky map. Its myth and mathematics today rest in the Musée du Louvre in far-off Paris.

The Temple (Temple of Hathor) stands close to the town of Dendera, just north of Luxor on the Nile’s west bank. It is renowned for its colourful ceilings and beautiful Hathor-headed columns. Built in Greco-Roman times, it was the centre of the sacred cow goddess cult, the worship of Hathor and a place for pilgrims seeking joy and healing.

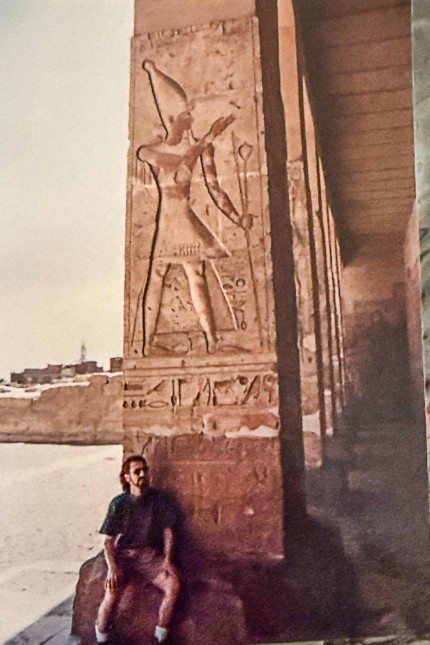

From Dendera, we travelled north for about 105 km by minibus (about 1.5 hours), crossing rural roads often shared with donkey carts and motorbikes. This route brought us to Abydos, one of the oldest and holiest cities of ancient Egypt. There stands the Temple of Seti I, dedicated to Osiris and is famous for its detailed carvings and the Abydos King List. It was a major pilgrimage destination, strongly linked to the afterlife and Egyptian kingship.

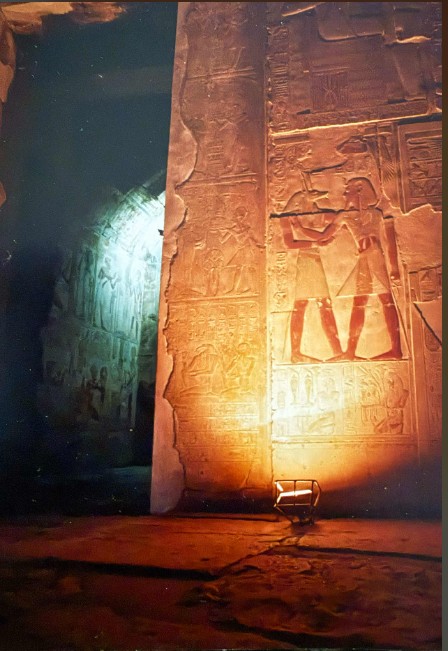

At Abydos, Seti’s temple unfolds seven chapels, shrines to Ptah, Re-Horakhty, Amun-Re, Osiris, Isis, Horus, and a seventh to Seti himself, as the deified king. I looked at the detailed hieroglyphs that tell the story of how a man—a pharaoh—becomes a god. It’s the heartbeat of Seti’s vision, carved in stone and still within our reach.

Meanwhile, in London, within Sir John Soane’s Museum, Seti’s vast alabaster sarcophagus glows like moon-milk in a sepulchral chamber. Inside and out it bears the Book of Gates; at the base, the sky-goddess Nu’t (Nuit, to Thelemites) stretches her protective body beneath the king, receiving and regenerating him. Recent programs at the museum—In Focus: Celebrating the Sarcophagus of Seti I—invite us to see the piece not merely as art, but as ritual technology: a portable underworld of names and stars.

Entering the Seven Chapels The seven chapels at Abydos form a ritual diagram in stone. Each shrine stages an exchange: king and deity, offering and response, the visible and the numinous. In the seventh, Seti is divinised, man made a god, not as vanity, but as the liturgy of the office he fulfilled: the human tasked to carry the god’s image until the image lives in the human. The King List nearby folds history into rite; the community remembers itself to remember the cosmos.

By the time I’d reached Abydos, it was the end of a long-held vow. The route we travelled was frequently unsealed dirt roads. I was physically exhausted, feeling sick from the constant jolting about in the vehicle. The heat had got to me, too. It took all my energy just to get to the hypostyle hall. This was the large, open area of the roofed entrance hall, supported by columns, and traditionally served as a processional and transitional space before the inner temple. I leaned against one of the 12 hypostyle columns. I was parched and reeling. I used the stone to steady myself before I could enter the temple complex. Many of my photographs at Abydos show the telltale signs that I could barely stand. Finally, deep inside the dimly lit temple, I entered Seti’s chapel. In the seventh chamber, I lay prostrate in a quiet savasana, corpse-pose upon living stone. My eyes and camera read the chapel walls as if they were my own funerary rite.

From my corpse pose, looking up at the carved hieroglyphs of Seti’s chapel, I wondered whether there were hints to be found about how Seti was made into a god. Examining the moment, preserved in stone, Seti did not do this deifying act to himself; it was enacted upon him. He was the instrument used by the gods and the fates during an allotment of time. Only the gods can make a god.

Working the Gates (for Witches and Scholars Alike)

Later, on my return to Sydney, I pondered these rites I’d witnessed preserved in stone. The Book of Gates is both study and praxis:

Name-work—To pass a gate, you speak the guardian’s name. Not superstition, but the ethics of address. The world is relationships; names are how we pledge reciprocity.

Hour-work—Twelve segments, sunset to sunrise: an underworld vigil any coven can structure a timed meditation or trance. Assign each hour a virtue, a trial, a trance, a rebirth. Record what arrives; repeat seasonally and let the pattern teach you.

Nu’t’s Embrace—The image floor of Seti’s sarcophagus is the image of Nu’t. Sky below, sky above: the sarcophagus enclosure becomes the body of Nu’t. We fall into her darkness to rise as dawn.

Ma’at as Measure: Let the “Table of Nations,” what the Egyptians called the “four races” of humankind, haunt your ethics. Who is welcomed in your circle? What do your rites do for justice, not merely power?

London by Candlelight, Luxor in Memory

Seti’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV17) discovered in 1817 by Belzoni remains one of archaeology’s great revelations. The sarcophagus Sir John Soane purchased in 1824 became his prized possession. Seti’s sarcophagus isn’t fragile because it is old; it is fragile because it is still working. The object is almost painfully beautiful: translucent calcite-alabaster, incised with a night-script meant to be read by the soul. In the translucent sarcophagus, Seti is both passenger and pilot.

(Hieroglyphic of the Book of Gates, 5th hour, detail of the solar barque with Amoun-Ra, as the midnight god.)

The Book of Gates is not a ‘book’ as we know it, but a sequence inscribed both in Seti’s tomb and on his sarcophagus—a choreography of the nocturnal journey, hour by hour, with guardians whose names must be spoken for passage with the solar god as companion. Nu’t, the eternal, is inscribed in the floor base of the sarcophagus, and her image is thought to have also been on the interior of the now missing lid. The missing lid and motif of Nu’t in the floor of the sarcophagus are like a metaphor: the lid removed, the sky-goddess within, the initiate’s entry point is revealed. In Nu’t’s embrace, the deceased are given a cosmological guarantee; the Great Mother of the deep sky and space promises rebirth.

Egyptologists read these images as funerary literature; modern witches will recognise an initiatory mapping of the afterlife. The twelve hours offer a ritual curriculum: naming, boundary-crossing, confrontation, and reintegration. This is not simply judgment before Osiris, though judgment is present, but a drama of union: the king becomes Osiris and Amoun to rise as Ra, as Khepri, the morning scarab that lifts the sun-disc again. The Soane sarcophagus remains a principal witness for the Book of Gates; even nineteenth-century publications leaned on it to establish an understanding of the sequence.

Among the most striking scenes associated with Seti’s tomb is the register of the “four races” of humankind—Egyptian, Asiatic, Nubian, Libyan—processing before the gods. For scholars, this is historical iconography; for practitioners, it is a reminder that initiation is not parochial. Ma’at—the balance that holds ocean to shore and oath to deed—isn’t tribal. The gates open for those who know the names and keep the right relationship.

(The photo of the sarcophagus of Seti I in the crypt of Sir John Soane’s Museum, evening by candlelight, London.)

I think of Soane’s sepulchral chamber—how the museum sometimes lights the sarcophagus by candle, returning the alabaster to its lunar nature. I think, too, of standing on that ramp in the Valley, peering down into the corridor where the first frames of the Book of Gates appear; and of my supine stillness in Seti’s chapel at Abydos. Three hours of one ritual: open air on the West Bank, stone rest in a temple, and lamplit in a London crypt. Belzoni’s 1817 discovery was more than a spectacle; it was only a beginning. The conversation continues—curators, conservators, and, yes, witches—turning the pages again. [1]

Seti’s legacy is the ground of the work. Deep sky above, deep sky below: the circle becomes the body of Nu’t. We fall into her darkness to rise as dawn.

Ma’at as Measure—Let the “Table of Nations” (the images that depict diversity of races) haunt your ethics. Who is welcomed in your circle? What do your rites do for justice, not merely power?

And for the Egyptologist with an esoteric ear: philology, palaeography, and conservation notes only deepen the enchantment. Precision is reverence. The more closely we read the registers, date the hands, and parse syncretisms at Abydos, the better we avoid romantic projection—and the more available the text becomes to real ritual imagination.

From Sydney’s headlands to the Thames embankment, from salt air at Bondi to desert dust at Luxor, the teaching is one: my choice of curiosity to make a pilgrimage of descent, provided me a way through the hours of night. Seti’s sarcophagus is a door; the Book of Gates is an invocation; and in Nu’t’s arms of embrace, we remember we belong to a larger, deeper skies.

(At the entry to Seti’s chapel at Abydos, showing the hieroglyphic image of Seti being guided by Anubis.)

Witches and scholars, over to you: What gate do you stand before tonight or in this season? Is Ma’at there to restore your choices—is Nu’t there to ask her to embrace you? And for those who have stood at Dendera, Abydos, or before Soane Museum’s glowing sarcophagus—what did the stones say to you?

[1] As of October 2025, the Sarcophagus of Seti I remains on permanent display in the Sepulchral Chamber (basement) of Sir John Soane’s Museum, London, where Soane installed it after purchasing the piece in 1824. Carved from translucent Egyptian calcite (alabaster), the sarcophagus is incised inside and out with passages commonly known as the Book of Gates, with the sky-goddess Nu’t depicted across the base. The object has been displayed within a protective glass case since 1866 (refurbished with clear safety glass in 2007).

Images: 3, 4, private collection Tim Ozpagan

1 – Amoun-Ra-Book-of-Gates (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehen#/media/File:Book_of_Gates_Barque_of_Ra_cropped.jpg)

2 – Soane-sarcophagus-late-event-candlelight (https://www.soane.org/sarcophagus-seti-i)

3 – Tim-Ozpagan-Abydos

4 – Tim-Ozpagan-Seti-Chapel

Resources

Sir John Soane’s Museum The Museum continues to programme talks around the piece—see In Focus: Celebrating the Sarcophagus of Seti I (15 October 2025, 1–2pm; tickets £5) and check the “What’s On” page for future dates; standard gallery hours are currently Wed–Sun, 10am–5pm, free entry. Sir John Soane’s Museum+1 It is presently displayed in the crypt section, called Sepulchral Chamber, of Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. https://www.soane.org/sarcophagus-seti-i

Sarcophagus of Seti I https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarcophagus_of_Seti_I

Scanning Seti: The Regeneration of a Pharaonic Tomb https://factumfoundation.org/our-projects/exhibitions-and-conferences/scanning-seti-the-regeneration-of-a-pharaonic-tomb/