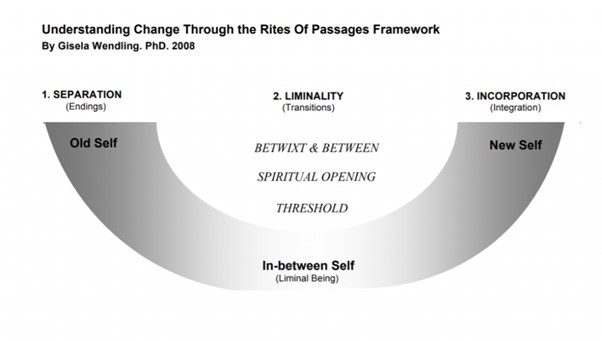

Rites of passage are ceremonial or symbolic rituals that mark significant life transitions or milestones, signifying a person’s progression from one stage of life to another. These rites are common in many cultures and serve to acknowledge and celebrate important events or changes in an individual’s life. Rites of passage often involve specific rituals, activities, or ceremonies that may have cultural, religious, or social significance. The three main stages of a rite of passage are:

Separation: This is the first stage, where the individual is separated from their current social status or role. It can involve physical separation or a symbolic detachment from their previous identity.

Transition: Also known as the liminal stage, this is the central and most critical phase of the rite of passage. During this period, the individual is neither in their old role nor fully integrated into the new one. It can be a time of uncertainty, learning, and personal growth.

Incorporation: In this final stage, the individual is reintegrated into society with their new status or role. They are acknowledged as having successfully completed the rite of passage and are welcomed into their new position or identity within the community.

Examples of rites of passage vary across cultures and can include:

Birth ceremonies: Welcoming a newborn into the community with naming ceremonies or infant blessings.

Coming of age ceremonies: Celebrating the transition from childhood to adulthood, often around puberty.

Initiation rituals: Formal ceremonies to mark the acceptance of an individual into a specific group or community, such as a religious initiation.

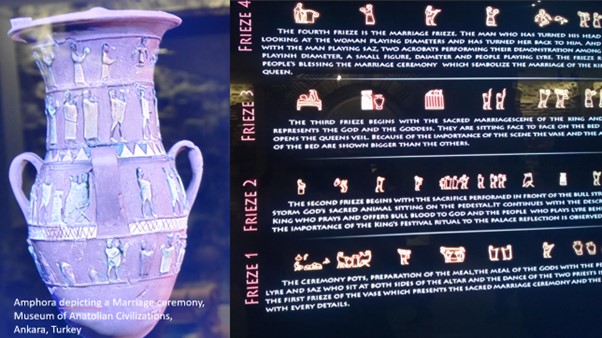

Marriage ceremonies: Celebrating the union of two individuals in a formalized marriage, or handfasting ritual.

Funerals and death rituals: Honouring the deceased and guiding their transition to the afterlife or the next realm.

In recent years we have seen the introduction of other ‘Rites of passage’ marking personal milestones, such as:

Graduation ceremonies: Recognizing the completion of educational milestones and transitioning into the next phase of life.

These rites serve as important cultural and social markers, reinforcing the values, beliefs, and traditions of the community while helping individuals navigate life’s changes and transitions. They often play a significant role in shaping individual identities and fostering a sense of belonging within a larger societal context.

Rites of Passage are sometimes also called Blood Rites – since most of the above-named rites centre around events in our lives which include ‘blood’ – childbirth, the first menstruation, the consummation of a marriage. Blood rites are also ceremonial rituals or practices that involve the use of blood. These rituals have been found in various cultures and historical contexts and may serve different purposes depending on the beliefs and traditions of the people involved. It’s important to note that the significance and nature of blood rites can vary widely across different societies, religions, and time periods and go beyond the scope of this article.

Religious Sacrifices: In some ancient cultures and religious practices, blood rites involved sacrificing animals or, in extreme cases, even humans to appease gods, seek blessings, or cleanse sins. The belief was that offering blood, which was considered a life force, would ensure divine favour or protection. (See the ‘amphora’ slide)

Initiation and Rites of Passage: Blood rites have been used as part of initiation rituals and rites of passage in certain societies. Drawing blood or inflicting controlled wounds on individuals might symbolize their transition from one social status or age group to another.

Blood Oaths and Contracts: Blood has been seen as a powerful symbol of commitment and trust in various cultures. In some societies, people would form blood oaths or agreements by mixing their blood together, signifying the seriousness of their promises. The concept of being ‘Blood Brothers’ and mingling each other’s blood in a ritual setting and swearing allegiance is very powerful. Breaking this kind of oath would be tantamount to killing the other.

Ancestral Veneration: In certain cultures, blood rites were performed to honour ancestors or connect with one’s lineage. Blood was viewed as a link between the living and the deceased, and rituals involving blood could strengthen this connection.

Healing and Magic: In certain forms of folk or traditional medicine, blood rituals were performed as a means of healing or to ward off evil spirits. Blood might be used in combination with herbs, chants, or other elements to harness its supposed mystical properties.

Symbolic Acts: Blood rites can also have symbolic meanings and significance. For example, in some religious ceremonies, wine or grape juice may be used to represent blood as a symbol of sacrifice or purification.

It’s important to acknowledge that while blood rites were and are practised in various cultures, many societies have moved away from such practices over time due to ethical, moral, and legal concerns. Some blood rituals have been criticized and condemned, particularly those involving harm or violence towards living beings. In the modern world, many practices once associated with blood rites have evolved into more symbolic or non-violent forms.

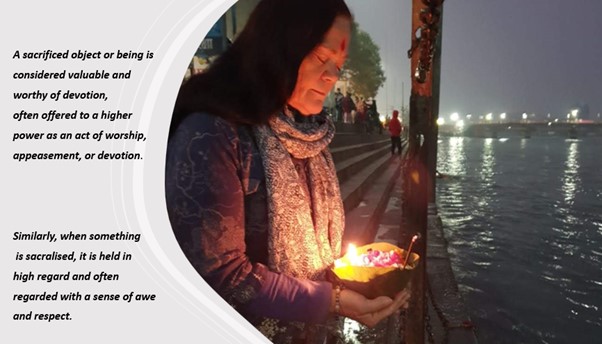

Sacrifice and sacralise

The word “sacrifice” has an interesting etymology that traces back to Latin and Old French. The English word “sacrifice” comes from the Middle English word “sacrifise”, which was derived from Old French “sacrifice” and ultimately from the Latin “sacrificium.” The Latin word “sacrificium” is a compound of two elements: “sacer” and “facere.” “Sacer” means “sacred” or “holy,” and “facere” means “to make” or “to do.” Therefore, “sacrificium” can be interpreted as “the act of making something sacred” or “the act of doing something holy.”

During the medieval period, the Latin word “sacrificium” was borrowed into Old French as “sacrifice”, maintaining a similar meaning to its Latin counterpart. The term “sacrifice” was later incorporated into Middle English, which was spoken from about the 11th century to the late 15th century. In Middle English, the word evolved to “sacrifise.” Over time, “sacrifise” underwent further changes, and the modern spelling “sacrifice” emerged. The word retained its original meaning of an offering made to a deity or a divine being, often involving the surrender or destruction of something valuable as a sign of devotion or appeasement.

Today, “sacrifice” is used more broadly to describe the act of giving up something for a higher purpose or a greater good, even if it is not directly related to religious practices. It can also refer to acts of selflessness or renunciation for the benefit of others.

What does sacralisation mean?

The term “sacralisation” is derived from the word “sacralise”, which refers to the act of making something sacred or treating it with great reverence and importance. In a religious context, sacralization involves the process of consecrating or making something sacred within a particular faith or belief system. This could include sacred rituals, objects, spaces (such as temples or holy sites), texts, or even individuals (like religious leaders or saints) that are revered and set apart as special and deserving of respect and devotion.

In a cultural context, certain practices, traditions, or symbols may be sacralised, elevating them to a level of significance beyond their practical functions. For example, national symbols, historical events, or cultural practices may be sacralised to foster a sense of identity, unity, and shared values among a group of people.

It’s important to note that the act of sacralization can vary widely across different cultures and historical periods. What is considered sacred in one society may not hold the same significance in another. Additionally, the process of sacralization can influence beliefs, behaviours, and societal structures, playing a significant role in shaping individual and collective identities.

What is the similarity between sacrifice and sacralise?

The similarity lies in their connection to the concept of making something sacred or imbuing it with special importance and reverence. Let’s explore the similarities between these two terms. Both “sacrifice” and “sacralise” involve the act of consecrating or treating something as sacred. When something is sacrificed or sacralised, it is set apart from the ordinary and mundane, becoming elevated to a higher, more revered status.

In both cases, there is a sense of reverence and significance attached to the subject. A sacrificed object or being is considered valuable and worthy of devotion, often offered to a higher power as an act of worship, appeasement, or devotion. Similarly, when something is sacralised, it is held in high regard and often regarded with a sense of awe and respect.

Both terms are commonly associated with cultural and religious practices. Sacrifices are frequently carried out as part of religious rituals, where offerings are made to deities or spiritual entities. Similarly, the act of sacralization can pertain to religious beliefs, objects, or spaces that are regarded as sacred within a particular faith. Additionally, sacralization can also extend to cultural practices, symbols, and social norms.

They can have symbolic meanings beyond their literal definitions. Sacrifices may symbolize devotion, submission, or the offering of oneself or something valuable for a higher purpose. Sacralization, on the other hand, symbolizes the recognition of something’s special value and its place within a broader system of beliefs or cultural significance.

Despite these similarities, it’s important to note that “sacrifice” and “sacralise” are distinct terms with their own specific uses and contexts. While “sacrifice” typically refers to an offering or relinquishing something valuable, “sacralise” relates more to the act of making something sacred or treating it with reverence, without necessarily involving an actual offering or destruction.

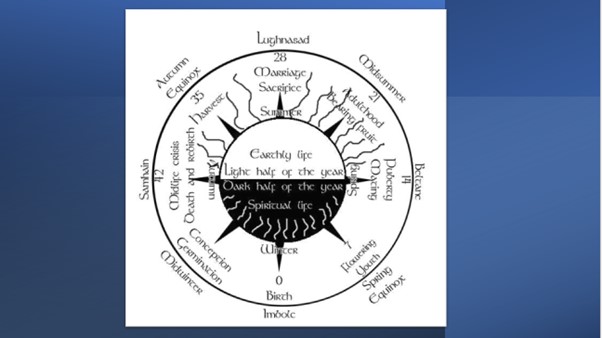

The Wheel of the Year, the Wheel of Life

This is a familiar symbol /map in Pagan and Wiccan groups. Indigenous people will also instantly recognise the Great Wheel of Existence.

(Re)sacralising the earth is the recognition and practice of Rites of Passage in the Wheel of the Year, the Wheel of Life… the celebration of birth at Imbolc, death at Hallowe’en and the turning of the seasons as Winter gives way to Spring and so on.

This is echoed in the Silver Circle Moon Calendar

Every year, every season, we attune with natural forces but also ancient practices. We may give our rituals and ceremonies a modern twist, but the underlying patterns of the Web of Life are unchanged.

What has changed dramatically is our position on this web of life, the web of wyrd. For centuries we have placed ourselves above Nature and become disconnected from the Earth, with Nature. However, if we realign ourselves and are Nature, albeit Human Nature, we have the possibility to truly resacralise the Earth.

The Rites of Passage, the Blood Rites, we use to mark the milestones on our life journey connect us to not only our ancestors but to the Starry Heavens.

“I am a Child of the Earth, but my race is of the Starry Heavens…’ Adapted from Orphic fragment 32

Pete Seeger in 1959 encapsulated this feeling of ‘being at-one’ with the rhythms of Nature in the now classic ‘Turn, turn, turn – to everything there is a season’.

“To everything, there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, a time to reap that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones,

and a time to gather stones together;

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to gain that which is to get,

and a time to lose; a time to keep,

and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew;

a time to keep silence and a time to speak;

A time of love, and a time of hate;

a time of war, and a time of peace.”

These are wonderful examples of using ancient texts and adapting them to modern times. The lyrics of Turn, Turn, Turn, are almost ad verbatim from the book of Ecclesiastes, as found in the King James Version (1611) of the Bible, (Ecclesiastes 3:1-8).

A renewed commitment, the fulfilment of our oaths and vows as we practice our rituals, rites and ceremonies can help to resacralize the Earth, our home, and our destiny.

References:

The three stages of the Rite of Passage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKP4cfU28vM

TURN! TURN! TURN! (Lyrics) – THE BYRDS

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turn!_Turn!_Turn!

“Turn! Turn! Turn!“, also known as or subtitled “To Everything There Is a Season“, is a song written by Pete Seeger in 1959.

https://www.hellenicgods.org/orphic-fragment-32—otto-kern..

https://www.hellenicgods.org/the-orphic-fragments-of-otto-kern

Full text:

“Thou shalt find to the left of the House of Hades a Well-spring,

And by the side thereof standing a white cypress.

To this Well-spring approach not near.

But thou shalt find another by the Lake of Memory,

Cold water flowing forth, and there are Guardians before it.

Say: ‘I am a child of Earth and of Starry Heaven;

But my race is of Ouranos. This ye know yourselves.

And lo, I am parched with thirst, and I perish. Give me quickly

The cold water flowing forth from the Lake of Memory.’

And of themselves they will give thee to drink from the holy Well-spring,

And thereafter among the other Heroes thou shalt have lordship…”

(trans. from Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion by Jane Ellen Harrison, 1903)

Museum of Anatolian Civilizations: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_Anatolian_Civilizations

Photos: Morgana