Who were the Etruscans?

Many people often think of the Greeks & Romans as being the parents of the Classical World in Europe and yet there was a civilisation in the heart of what we now called Italy many centuries earlier. Forgotten by many it was the Etruscans who influenced the Romans. As often the case, in Europe, it was the Romans who wrote down the history.

But first of all a little bit of background information:

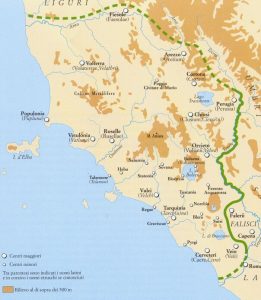

Where is Etruria, the area where the Etruscans are generally associated with?

And in more detail:

Today this area is better known as Tuscany. Etruria was always famous for its fertile ground. The region of Tuscany and the north western-part, Latium, formed together Etruria.

Timeline

Although the Etruscans were rivals of the Romans, they supported the Romans in the 2nd Punic War against the Carthaginians. In 90 BC the Etruscans were given the same rights as Roman citizens, whereby they effectively became a part of the Roman empire.

But let’s go back to the time before the Roman Empire. Where did the Etruscans come from? There still seems to be a lot of speculation. According to Herodotus, the Etruscans came from Lydia. The story goes something like: “around 800 BC, there was a famine in Lydia (in what is now western Turkey). Eventually the king, “divided the people into two groups, and made them draw lots, so that the one group should remain and the other leave the country.”

And Yaroslav Gorbachov, a linguistics professor at the University of Chicago, describes, “the Etruscans shared some unique customs with the Lydians and Louvians as well — like the practice of Herosposy, a form of divination from inspection of entrails. … Gleaning the will of the Gods through inspecting the livers of sacrificed animals.”

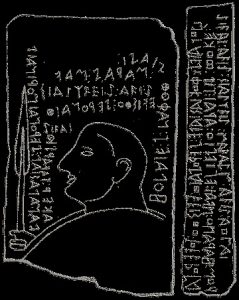

This would infer that the Etruscans came from near to Anatolia. Also when looking at the origin of the Etruscan language I came across this information about the Stele of Lemnos:

A little north of Poliókhni lies that village of Kaminia where, in 1885, as part of a church wall, the so-called Stele of Lemnos was discovered. This stele is generally dated at an epoch (shortly) before the Attic conquest of the island, and is now on exhibition at the National Museum of Athens. Portraying a warrior holding a spear, its paramount scientific and historical meaning is constituted, however, by two inscriptions. They are written in a hitherto unknown variant of the Greek alphabet and a language equally unknown in 1885; which language, from obvious reasons, was called Lemnian.

(stele of Lemnos)

“Further — which has been only briefly mentioned here with Luvian maua — there exist enough similarities between the Etruscan and Lemnian languages and the so-called Anatolian languages (in Asia Minor) to show that the roots of the Etruscans in Italy must be sought in the northwest part of Asia Minor — approximately in the region of Troy. And this might well form the historical core of that myth of Trojan origin, which the Romans have borrowed from their neighbouring nation, in order to claim it for themselves.”

(http://www.etruskisch.de/pgs/og.htm)

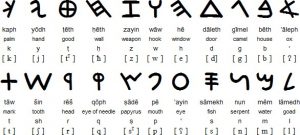

Others have claimed that Etruscan is very similar to Slavonic languages but I checked with a couple of Russian friends who said didn’t see any similarities. In fact, we saw more similarities with Phoenician when we looked at some examples such as this

(Phoenician alphabet)

“The Pyrgi tablets” are laminated sheets of gold both in Etruscan and Phoenician languages. They are exhibited at the Etruscan Museum in Rome – “Museo di Villa Giulia”

Structure of society: How did the Etruscans structure their society? And which things occupied their lives. According to Larisse Bonfante: “Etruscan society was an aristocratic society, and the funerary art that we see comes from the tombs of important families. Not surprisingly, there is an emphasis on the family. Etruscan art of the fourth century often illustrates the reunions of families that take place when members of the younger generation join their deceased relatives.” (Bonfante)

With respect to rituals and “Rites of Passage” she writes: “Scholars have suggested a number of motives for such horrific rites, and these can be applied to the situation in Etruria as we understand it from archaeological and iconographic evidence. Sacrifices were religious practices performed as offerings to the gods, to appease them and avert disasters, to mark the establishment of a new foundation, and as funerary rituals, to honor dead ancestors, and satisfy hostile ghosts. The killing of enemy prisoners could magically bring about the defeat of the enemy, or at least prevent their return.25 What all these kinds of human sacrifices have in common is that they were carried out in public by the family or community, which took part in their performance, and thereby enhanced the bonds that held them together as a group.” (Bonfante)

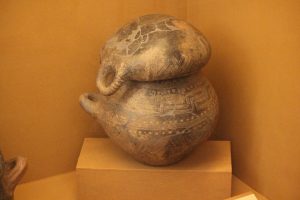

Funerary urns:

(Etruscan museum, Volterra)

(Etruscan museum, Volterra – CS)

(Etruscan museum, Volterra – CS)

(Etruscan museum, Volterra – CS)

(Etruscan museum, Volterra CS)

That the rites and celebrations are amply depicted on many of these urns. The ones with ‘lids’ and placed in little sanctuaries of their own would seem to indicate that the urns were not set apart and would form an integral part of everyday life. The position of women was renowned and they were seen equally with men.

In her excellent paper “Etruscan Women and Social Structure” (© 2011) Max Dashu has described in detail the position Etruscan women enjoyed.

She writes: “Etruscan women, whether married or unmarried, were famously free. Sarcophagi display their aura of complete self-confidence, and the affection of their male partners. They who took part in public events participated in councils and in nude athletics. The liberty of Etruscan women was notorious among the Greeks and Romans, who were scandalised at the liberty they enjoyed. Women socialised and drank at banquets with men, reclining with their chosen partners.”

(Sarcophagus and lid with husband and wife, Etruscan, 350–300 B.C., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Credit: Sebastià Giralt via Flickr)

(Etruscan sarcophagus from Cerveteric, 520 BC Museo Nazionale de Villa Giulia, Rome. Photo by Fraxe 2009)

She writes: “Greek men interpreted Etruscan women’s liberty as looseness, because of severe restraints on females in their own society. They projected absolute sexual licence onto Etruscan women, in a pattern dubbed “topsy-turvy” world, in which Hellenes projected absolute reversals of their own social codes onto peoples they saw as Others. Theopompos ran this female freedom through his own Hellenic framework that put men at the centre:

Sharing wives is an established Etruscan custom. Etruscan women take particular care of their bodies and exercise often, sometimes along with the men, and sometimes by themselves. It is not a disgrace for them to be seen naked. They do not share their [banquet] couches with their husbands but with the other men who happen to be present, and they propose toasts to anyone they choose. They are expert drinkers and very attractive. The Etruscans raise all the children that are born, without knowing who their fathers are.

[Theopompos, Histories CLII, in Lefkowitz and Fant, 88-89]

to be continued…

Hi Morgana, thank you for the link! Looks beautiful: nicely illustrated, well documented. I’m looking forward to reading it…

It is not always easy to find things in the wiccan rede online 🙂

Hi Magriet, Part 2 is also in this issue, see: http://wiccanrede.org/2017/02/etruscans-myth-magic-part-2/

Interesting… Looking forward to the next part. Thank you, Morgana!