At this time of the year our thoughts tend to become reflective. The days are becoming shorter and for many of us the coming winter months mean long evenings inside. It can be a lonely time – a time in which we are ‘thrown’ back unto ourselves. But it can also be a time in which new ideas are shown. In our reflections we may realise that there are a number of things in our lives which are not necessary. In nature we see too that after the harvest the seed is all that remains and yet within that seed everything is contained for further growth. The seed is the potential and is contained within the earth’s bosom until Springtime when it will germinate.

At Hallowe’en it is this turning point, the ‘bringing back to the essence’ which we celebrate the dying of the old year and the conception of the new year, or the reaffirmation of life. It involves the descent into the Underworld. In virtually all the mythologies there is an underworld, a place in which we are often judged and purified and after a period of rest, resurrected.

The archetype of the Underworld is vast and it would take more than one article to fully explore this concept. As is often the case the archetype can be examined on many different levels. The underworld can be seen for example as a journey or passage in our evolution, as an initiation. Or it can be seen as a prelude to our birth into the spiritual world. In any event we are brought back to our essence – as the Goddess Ishtar, we are stripped of our jewels and have to face the Lord (or Queen) of Death.

For most people the idea of death is a terrifying thought. What is waiting for us beyond the veil? Is there a heaven or hell? Is there life after death? It is hardly a consolation to realise that millions of other people have crossed over the threshold. No one can really prepare us for the journey – as much as no one can prepare us for initiation. We may know the general procedure but the experience is unique to each person, as every experience is.

We can hope, however, to remove the fear which may destroy our full appreciation of the experience.

Each year as we celebrate Hallowe’en we are reminded of the confrontation with the Lord of Death. We are reminded too of our loved ones who have already passed on. And yet we also celebrate the continuation of life, perhaps not in the same guise as we’ve known, but as the spirit of life.

(Magic-Raven-Samhain-Altar-2013)

As we celebrate we come to realise that death is only another aspect of life’s cycle – an important aspect. The very painful part of death is having to come to terms with the fact that a loved one is no longer physically present. It can be very difficult for those left behind to realise that the person in question is entering a new phase of his or her evolution. In some religions death is celebrated in a joyous way, which may be difficult to understand for those of us who are used to experiencing death as a mournful event.

As I said earlier no one really knows what happens when we die although virtually every culture has an image or picture of the period following death. In this article I hope to illustrate several different images of the underworld, from a mythological point of view.

It is generally known that the death cult played an important role in Egyptian Mythology. There is enough evidence of mummification and ritual embalmment for us to surmise that death was in important event in Egyptian life. Osiris who was at first a nature god became the Egyptian god of the dead. One of his names was Osiris Khenti Amenti, “Lord of the Westerners”, the West being the place where the sun sets and where the dead dwelt.

In many respects it is not surprising that a god of vegetation became God of the Dead – he was constantly dying at harvest and being reborn at germination time.

Osiris, who introduced agriculture to the Egyptians, was also a wise king. After Egypt was civilised he wished to civilise the rest of the world. During his absence Isis ruled Egypt, also wisely. When Osiris returned the kingdom was in perfect order, but it wasn’t long before there was a plot to overthrow him by his brother Set. Osiris was killed and put into a coffer which drifted to the base of a tamarisk tree, and was subsequently found by Isis.

Later she brought the coffer back to Egypt and hid it in the swamps. Set however found it by chance and in order to destroy the body forever he cut it up in fourteen pieces and scattered it all over Egypt.

Isis was however determined to recover the pieces and started her search. She managed to find all the parts except the phallus. She ritually embalmed all the parts which restored the god to eternal life. After his resurrection he retired to the “Elysian Fields’ where he then welcomed the souls of the death.

In the Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’ Osiris is seen as the greatest of gods and it is he who judges the dead and determines their future destiny. The ‘Book of the Dead’ is said to have been written by Thoth who with Isis, Horus and Anubis helped to resurrect Osiris.

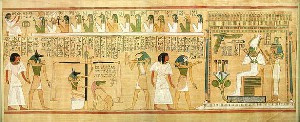

In the Book of the Dead the cult of Osiris is the basis of the book. Osiris points out the necessity of leading a pure life and gives instruction for attaining eternal life. In the Book of the Dead there is a judgement scene illustrated in the Papyrus of Ani (now in the British Museum). In the centre of the Hall of Judgement there is a scale. Maat, the Goddess of Truth and Justice stands next to the scale, ready for the weighing of the heart of the deceased.

When a person died he had to cross the stretch between the lignin and the dead. Thanks to the talismans placed in the sarcophagus with the passwords from the Book of the Dead the deceased would reach the Hall of Judgement. After having kissed the threshold the deceased would enter the Hall, where Osiris sat and where the scales were. There was also a monster present, “Amernait”, who would devour the hearts of the guilty. Around the Hall sat 42 judges who would judge special aspects of the deceased’s life. The deceased called each of the judged in turn by their name which proved that he did not fear them.

Then followed the weighing of the soul. Anubis or Horus would place the ideogram of Maat, a feather, symbolising truth, on one half and the heart of the deceased on the other half. Thoth recorded the weight on a tablet and told Osiris the result. If the scales were in perfect balance, Osiris would render a favour able judgement and the deceased would enter the dominion of Osiris and enter into everlasting life and happiness.

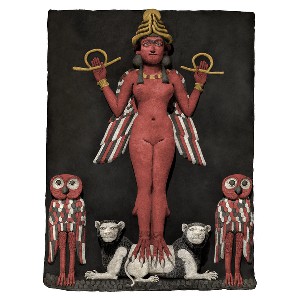

The underworld of Assyro-Babylonian mythology was under the earth. It was a land of no return and to enter it the deceased had to pass through seven gates, abandoning a part of their apparel at each gate. At the last gate there were completely naked and imprisoned in the ‘dwelling place of the shadows’. At first the “Princess of the Great Earth’, Ereshkigal, ruled over the infernal regions, but later Nergal became her husband. Ereshigal gave him a a tablet of wisdom to hold and Nergal, who had been a God of Destruction, became the overlord of the dead. One person who managed to enter the underworld and return was the Goddess Ishtar. Ishtar, whose name means ‘Daughter of Light’ was a warrior goddess, In her youth she had loved Tammuz the God of the Harvest. Overcome with grief she tried to rescue Tammuz from the underworld and made the descent into the infernal regions.

At each of the seven gates she stripped off her jewels and finally came face to face with Ereshkigal.

Ereshkigal made her prisoner and on Earth there was great sorrow.

“Shamash and Sin, her father, carried their grief to Ea. Ea, in order to deliver Ishtar, thereupon created the effeminate Sasushu-Namir, and sent home to the land of no return, instructed with the magic words to restrain the will of Ereshkigal. In vain the queen of the infernal regions strove to resist. In vain did she attempt ‘to enchant Sasushu-Namir with a great enchantment’.

Ea’s spell was mightier than her own, and Ereshkigal had to set Ishtar free. Ishtar was sprinkled with the water of life and, conducted by Namtaru, again passed through the seven gates, recovering at each the adornment she had abandoned.”(Larousse).

(The Queen of the Night relief Old Babylonian)

Esther Harding: “Ishtar had taken the dread journey to the underworld and although she was sore beset, she eventually conquered the darkness and rose again as the new moon, small at first but with power to recreate herself… she symbolises the power of life from the dead, Thus, like Sinn, who preceded her, and like Osiris of the Egyptians, she became Goddess of Immortality, the nape of life after death.

In Greek mythology too the underworld is a place of shadows. It too was situated under the earth. Certain caverns and rivers which flowed underground marked the entrances to the underworld. Two of these rivers were called “Acheron” (River of Sadness”) and “Cocytus” (River of Lamentation). Preceding the actual underworld there was the “Grove of Persephone” which had to be crossed before entering the gate of the Kingdom of Hades. The gates were guarded by monstrous dog called Cerberus.

In the underworld, flowed subterranean rivers – the Acheron, Cocytus, Phlegeton, Lethe and Styx.

“Acheron was the son of Gaea, He had quenched the thirst of the Titans during their war with Zeus and been thrown into the underworld where he was changed into a river. To cross Acheron it was necessary to the apply to the old Charon, the official ferryman of the underworld.

He was a hard old man, difficult to deal with. Unless before embarking the shade of the deceased newcomer presented Charon with his obulus, he would mercilessly drive away an intruder so ignorant of local usage. The shade was then condemned to wander the deserted shore and never find refuge. The Greeks therefore carefully put an obolus into the mounts of the dead.

The Styx surrounded the underworld with its nine loops. The Styx was personified as a nymph, daughter of Oceanus and Tethys. She was loved, it was said, by the Titan Pallas and by him had four children. As a reward for the help she rendered the Olympians during the revolt of the Titans it was decided that the Immortals should swear by her name, and such vows were irrevocable.

Those who drank the waters of the Lethe forgot the past. Lethe flowed, according to some, at the extremity of the Elysian fields, according to others at the edge of Tartarus. The Elysian fields and Tartarus were the two great regions of the underworld.’ (Larousse).

Hades was absolute master over the underworld. He was also known as Pluto. It was Hades who abducted Kore to his realms whilst she was picking flowers. Her mother Demeter came to search for her but was unable to rescue her completely because Kore had eaten the fruit of the pomegranate. Later Hades and Demeter made a compromise in which Persephone (Kore) would spend part of the year with Hades and the rest of the year on earth (i.e. during the fertile part of the year.

(Hecate)

Hecate who was originally a moon goddess was also a divinity of the Greek underworld. She descended into the underworld when she was thrown into the Acheron to try and remove a stain caused by her coming into contact with a women who had just borne a child. Hecate tried to hide with the woman after she had angered her mother Hera by stealing her rouge.

In the underworld Hecate was the Goddess of Enchantments and Magic. When she appeared on earth she was accompanied by hounds, a symbol of the moon. She often appeared at crossroads or at graves. At crossroads statues of Hecate could be found and at full moon offerings were made to her to appease her.

In the underworld the deceased appeared before Hades and the other judges. Once the deceased had been judged there were either cast into the Tartarus or sent to the Elysian fields. Tartarus was a prison for all those who had committed crimes against the gods whilst the Elysian Fields were a place of rest and tranquillity. The Elysian Fields were also called the Islands of the Blessed.

In Celtic mythology we come across a similar concept of the Elysian Fields in the ‘Field of Happiness’ or Tir na nOc. This was a magical place where warriors were healed of their wounds and the dead were restored to life. It was a place of feasting and lovemaking. Tir na nOc was also known as the ‘side’, a place where time did not exist.

As a counterpart to Tir na nOc there were also things to be feared, for example Ysbaddeden, in the tale of Culwch and Olwen.

Looking further north to Teutonic mythology we find a totally different concept of the underworld. In the earliest tradition of the world as a huge ash tree, Yggdrasil, which is more familiar. This world tree was divided into three main regions; Asgard, the abode of the gods; Midland, the abode of man, and at he bottom there were three roots. One of the roots stood over Niflheim of the underworld, which was ruled by the Goddess Hel. In one of the Norse myths concerning the death of Baldur we are again reminded of Osiris, Tammuz or of Adonis. In fact, Baldur like Adonis means “Lord”. Once again the beautiful young god of vegetation dies.

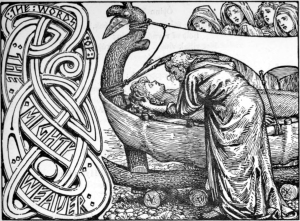

(Baldur)

Baldur had been troubled by dreams of impending evil and danger. He told the Aesir (the Gods) and Frigg his mother begged every living thing to promise never to harm him. This they did and subsequently the Aesir put him to the test by throwing stones and other projectiles to see if he could be harmed. But he remained unhurt. Loki who was watching became angry, so he disguised himself as an old woman and went to Frigg. He asked her what the Gods were doing and Frigg told him about the oath all the living things had sworn not to harm Baldur. “What!” exclaimed the old woman, “have all things sworn to spare Baldur?” “All things,” replied Frigg, “except one little shrub that grows near Walhalla, and is called Mistletoe, and which I thought too young and feeble to crave an oath from.”

As soon as Loki heard this he went and made a dart from the Mistletoe.

He returned to where the Gods were and found Hodur who was not partaking in the fun, because he was blind. Loki however offered to help him by directing his arm and in so doing Hodur threw the Mistletoe dart. The dart pierced Baldur and Baldur felt down lifeless.

When the Gods realised what had happened they began to discuss a way of undoing this terrible wrong. Frigg asked if there was anyone who dared to descend into Niflheim and offer Hel a ransom if she would allow Baldur to return to Asgard. Hermod, Odin’s son, stepped forward and mounting Sleipnir, Odin’s horse, he galloped towards Niflheim. For nine days he rode until he reached the river Gyoll which he passed over by a bridge of glittering gold.

The maiden who guarded the bridge asked him what he sought since he was not yet dead. He asked her if Baldur had crossed the river. To which the maiden replied that he had, and pointed towards the barred gates of Hel. With the help of Sleipnir, Hermod managed to clear the gates and ride on to the palace where he found Baldur.

The next morning he met Hela and he besought her to let Baldur come home, since all the Gods love him. She replied “If all the things in the world, both living and lifeless weep for him, then he shall return to life; but if any one thing speak against him or refuse to weep, he shall be kept in Hel”. Hermod rode back to Asgard and told the Gods what he had heard. The Gods then despatched messengers all over the world to beg everything to weep for Baldur. All living things willingly complied with this and the messengers returned delighted to Asgard. On their return however they saw a giantess Thökk sitting in a cavern. The begged her to weep Baldur out of Hel but she refused and said “Let Hela keep her own”. The giantess was of course Loki and so Baldur had to remain in Hel.

Later however Loki did not escape his punishment. Odin found him, after he had tried to escape the Gods’ wrath. The bound him with chains and suspended a serpent over his head, whose venom dropped on to his face.

Here he remained until Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods. (Taken from Bulfinch’s Mythology).

Only after Ragnarok is Baldur resurrected and allowed to return to peace.

In virtually all the myths mentioned above there are parallels, especially in the case of the dying god of vegetation who descends into the underworld, only to be given eternal life.

Another parallel is the Underworld as a place of rest and restoration.

(Hades)

Also many mythologies include the possibility of the living meeting with the death – something which in Craft philosophy is a feature of Hallowe’en, when the veil which separates our world from the world of the dead, and the Gods, is particularly thin. Our own Craft Legend of the Goddess descending into the Underworld runs parallel to some of the myths discussed here. Even so, it is a very moving archetype, which can be used on more than one level, because each person has some form of the Underworld within himself – a region not to be entered unless one is completely ‘naked’, i.e. unadorned, aware of one’s own positive and negative points, and fearless!

References and notes:

‘The Underworld’ published originally in Wiccan Rede, Autumn 1985

Spanish Translation (With thanks to Alder Lyncurium).