Otherwise Than the Binary. New Feminist Readings in Ancient Philosophy and Culture

Edited by Jessica Elbert Decker, Danielle A. Layne, Monica Vilhauer

SUNY series in Ancient Greek Philosophy

SUNY Press, 2022 (paperback 2023), 368 pag., ISBN 9781438488790 (hardcover, $ 95) / 9781438488806 (paperback, $ 33,95). Digital formats also available.

In light of recent discussions, the word ‘binary’ immediately calls ‘gender’ to mind. Emotions run high around this subject, but it isn’t always clear what exactly is meant. As I understand it, the binary is a way of dividing phenomena and concepts in two opposing classes, and grouping together phenomena supposed to belong to the same group. Sexual difference and gender are probably the most encountered aspects of the binary. But it’s about more than just sex or gender as such.

If there are only two groups something can be assigned to, other things will be in the same group, and everything in the same group will be considered to belong together, to be connected at some level. And everything not in that group will be considered to be in the opposite group. This applies equally when the two groups are conceived as two halves of the whole: dividing in two means creating two opposed, mutually exclusive classes. If ‘masculine’ is grouped together with for instance sun, day, visibility, knowledge, order, culture then concepts like life, health, truth etc. must belong to the same half; and moon, darkness, dreaming, poison, secrecy etc. will be assigned to the opposite ‘feminine’ half. These underlying cultural notions come to light when, for instance, dark-skinned persons are thought to be less cultivated than light-skinned persons; when women are required to be socially invisible; when information given by a man is considered more reliable than the same information given by a woman.

When things don’t quite fit into either category, for the sake of clarity or aesthetics they are often made to fit. One should be careful in this endeavour, and not mistake created order for natural order. Clusters of associations can provide shortcuts to understanding the world, but obviously in concrete situations can mislead as well as inform.

The dualisms of binary thinking are almost always at play, consciously or unconsciously, and often one of the two is preferred over the other. The preferred one then readily becomes normative. Sometimes the order is reversed by societal developments, for example in our culture’s preference for ‘young’ and ‘new’ over ‘old’. Within subcultures, sometimes the order is upturned in protest to the so-called superiority of what became the norm, and notions like darkness, the body, intuition, softness, the temporal, polytheism, etc. are given prominence over light, mind, rationality, firmness, eternity, monotheism, etc. As a counterbalance to the dominant view, such a reversal may be necessary. But it still functions as a binary, and risks falling into the same trap of putting one up as the norm, to the diminution or even exclusion of the other. Sometimes a third element is added. But this in itself doesn’t change the traditional rating of positive/negative of the earlier two.

Even for those who don’t embrace ideas of – for instance – women’s inferiority, it is difficult to be entirely free from the thought patterns underlying such ideas. On social media I once saw a black-and-white picture that was supposed to show man-sun-thinking-culture and woman-moon-feeling-nature as complementary halves; different in being, but equal in worth. It consisted of drawings within the yin-yang symbol. But in this picture the ‘masculine’ half filled the upper half of the circle, and the ‘feminine’ the lower half, which made it to look as if the female was a distorted reflection in dark waters of the shining male above. Which comes eerily close to the traditional Aristotelian view of humanity as essentially male, with women as deficient men. When this was pointed out, the person who posted the picture got quite upset and defensive: this was not what they meant at all.

Plato’s Cave. Engraving by Jan Saenredam, 1604. Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. – Light versus shadows, truth versus opinions in Plato’s famous Allegory of the Cave.

To remedy a problem, it is customary to look for the roots of the problem. In Otherwise Than the Binary, a major root of problems connected with the binary is located in Plato’s writings. To examine the huge cultural influence of his philosophy, with its division between the world of pure Being – the ideal, eternal Forms to be understood by the intellect, and usually associated with the masculine – and on the other hand the changing world of embodied Becoming – physical phenomena, grasped by sense perception, and usually associated with the feminine – the eleven chapters of the book are arranged in three parts: before Plato; Plato; and after Plato.

The chapters are by different authors on different subjects, but frequently referring to one another. There are also underlying connections that come to mind when you lay the book aside and let your thoughts wander about what you’ve read. It could be enlightening to read the book not only article by article, in the given order or maybe choosing the chapters that seem most appealing; but also criss cross through the articles; following as it were the scent of khôra across the pages, or the themes of oracular language, the relation between humans and gods, the power of desire…

In this review, I can’t possibly discuss all the fascinating and important ideas the book offers, so I’ll limit myself to a few themes that may be of special interest to readers of Wiccan Rede Online.

Myth, Divination, and the Pre-Platonic

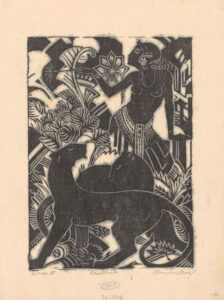

Circe and two black panthers. Woodcut by Henri van der Stok (1880 – 1932). Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. – Magic, darkness, femininity and wild nature in one powerful image.

The first part of the book: ‘Myth, Divination, and the Pre-Platonic’ opens with Andrew Gregory asking: ‘Was Homer’s Circe a Witch?’ This question may surprise readers of Wiccan Rede Online. Of course she was… wasn’t she? Now it gets philosophical, for what is a witch, what makes a witch a witch? But remember, this is about Homer’s Circe, not the Circe of later writers or painters. Gregory informs us that in the Odyssey, Circe is never called a witch; neither in the descriptions nor in how other persons of the epic address her. There is no word for witch or witchcraft at all in Homeric Greek: Circe is a goddess.

But does this goddess conform to later notions about witches? Can she influence the weather, does she have a special wand or staff, use magic potions, raise the dead, call on evil powers to work her magic, etc.? In the Odyssey, Circe has some – not all – supposedly ‘witchy’ characteristics, but more importantly: so do others. Why then is it that Circe is now known as a witch, but Hermes and Athena as gods, not witches? Gregory writes: “The modern Western idea of a witch has been generated within patriarchy and there are many gender assumptions implicit in that construction. Those gender assumptions are necessary for the construction of Circe as a witch. (…) If Circe is held to fit some supposed modern pattern of witchcraft, then it must be recognized that many other Homeric deities fit this pattern as well, perhaps a whole pantheon of them.”

Andrew Gregory argues that a misogynistic reading has evaluated powerful female characters only in relation to the male protagonist: did she help him, as Athena helped Odysseus? Then she is considered a goddess. Did she have her own agenda that (partly) crossed his plans, as Circe and Calypso did? Then she is considered a witch. The paper didn’t entirely convince me (for instance, I believe it’s very well possible to consider Hermes both a god and a witch), but I think everyone can agree with Gregory that female characters deserve to be considered in their own right, instead of being judged according to their usefulness to a male hero.

In ‘The Roots of Life and Death in the Homeric Hymns and Presocratic Philosophy’, Jessica Elbert Decker shows that ancient myth and philosophy were not two completely different and separate ways of looking at the world. They shared their poetic approach. Just as the poets Homer and Hesiod told their stories as inspired by goddesses, so did the philosophers Parmenides and Empedocles present their ideas as revelations by goddesses. En passant is pointed out that the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite is a hymn to proclaim the might and workings of the goddess, as you’d expect from a hymn. On the surface it might appear as a tale of her defeat, and how “[i]t’s a lucky thing that her daddy Zeus came along and saved her from herself”. But this appearance may well be a playful and cunning devise of the goddess who delights in laughter. This chapter was such a joy to read. It reminded me how important, but moreover how pleasurable it is to read texts slowly, carefully, more than once, and with an eye for wordplay, irony, allusions, narrative frame, multiple layers, and other meanings between the lines.

Platonic Transformations

Socrates and Xanthippe. Etching and drypoint print by Jan Tersteeg, 1765. Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. – Socrates’ wife Xanthippe is said to have been no meek little housewife. She frequently spoke her mind, and according to one story (told by Diogenes Laertius and others), once when he was talking to his pupils, she scolded him and threw water over him. Water, or according to some, piss from the chamber pot. Socrates reacted by remarking: “After thunder comes rain”. In this image, Xanthippe doesn’t look very angry, but rather seems to play a prank on her husband.

In the second part, ‘Platonic Transformations’, I experienced the same sensation reading Hilary Yancey’s and Anne-Marie Schulz’s paper ‘As Much Mixture as Will Suffice. Socrates’ Embodied Intermediacy in Plato’s Phaedo and Symposium. The title of their article is taken from the dialogue Phaedo, which tells about Socrates’ last hours before his death. The Symposium describes a drinking party at which the participants talk about Eros. For Yancey and Schulz, the key concept to understanding those dialogues is ‘mixture’.

They argue that, contrary to what is often thought, Plato is not urging philosophers to live as if they were only soul, rejecting the physical (an interpretation still encountered in the phrase ‘Platonic love’). It’s true that according to him, the body with its desires and emotions shouldn’t dictate one’s life; but neither should it be denounced. Feeling physically attracted to beautiful bodies can be an initiation, and the first, necessary step towards desiring wisdom. A philosopher (lover of wisdom) should strive to a ‘sufficient mixture’ of body and soul. Not too much or too little of either, but a mixture that is exactly measured to its purpose. Socrates is shown as an example of someone who succeeded in this.

Monica Vilhauer’s article ‘Overturning Soul-Body Dualism in Plato’s Timaeus‘ discusses a dialogue that has been hugely influential in philosophy and esotericism, if only for its mention of Atlantis, the Demiurge (or ‘craftsman’ as it is translated here), and the World Soul (here ‘soul of the cosmos’). Vilhauer argues that within the text, there are clues to disrupt the common binary and misogynistic reading of Plato.

A central notion here is chôra (also spelled khôra), a word that can be translated as ‘place’ or ‘space’. It isn’t the realm of passive, receptive matter, but turns out to be a different metaphysical feminine. In the dialogue that bears his name, Timaeus proposes it as a third kind, between Being and Becoming. He says it is passive, but his speech shows it is also active. He indicates that chôra is difficult to describe. It doesn’t fit in the languages of logos or mythos, but has its own, dream-like, oracular language.

Late Antique Destabilizations

I can’t leave without mentioning William Koch’s ‘Hekate and the Liminality of Souls’ in the third part: ‘Late Antique Destabilizations’. In the Middle Platonism of the Chaldaean Oracles, the ancient goddess Hekate was identified with the cosmic soul of the Timaeus. Koch describes how in this view the soul of the cosmos is problematic in a similar way to the soul in Plato’s own philosophy: it had a central role, and at the same time didn’t neatly fit in the binary Being/Becoming.

In the Chaldaean Oracles, Hekate and other divinities teach philosophy in the form of oracles. This reminded me of the goddesses of Pre-Platonic philosophers, who dictated their philosophical truths in verse.

Hekate as cosmic soul was associated with the moon. The moon was the station where souls after death, on their way to the eternal realm were purified; or in the reverse direction got their temporal specifics on their way to be born. Hekate was traditionally a goddess of passages like death and birth, and in this aspect became as it were the khöra of Platonism. She was imaged as having two faces, like Janus. Her domain was an ambiguous ’third’ between the two main realms of Being and Becoming. Her function was essential, but she didn’t preside over a separate realm in her own right.

In contrast with the Chaldaean Oracles, the later Greek Magical Papyri visualise the goddess not just as dual but also as three-headed or triple-bodied. This referred to her ancient powers over the three realms of earth, sea and sky. Hekate was queen of the daimons, metaphysical beings closer to mankind than the gods. In Platonism, the gods were more and more conceived as distant perfect beings, less ‘human’, and not as responsive to prayers as daimons were to invocations. (Note here that in the Symposium, Diotima is said to have called Eros not a god, but a daimon megas, a ‘great spirit’.) Koch states that in the Greek Magical Papyri, a Pre-Platonic world view has survived. This implicates that working with the Greek Magical Papyri could offer an escape from the Platonic binary.

Medea offers a ram at the altar of Hecate and Hebe, with Proserpina and Pluto present. Engraving by René Boyvin, after Léonard Thiry, 1563. Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. – Hecate (the statue on the left) has three faces.

In conclusion: this book gives several fascinating views on aspects of ancient philosophy and culture, with consequences for our time. Without at least some knowledge of the classics, philosophy, and feminist thinking, the discussions in this book can be difficult to follow. An academic library nearby would be nice, to investigate the source texts (or translations) in more depth. I didn’t have that, but I was tempted to take up dozens of other books next to this one, to refresh my memory and expand my knowledge. Otherwise than the Binary is no easy holiday reading, but it’s certainly worth the effort. I found it immensely captivating and thought-provoking.