2017 was going to be the year that I wanted to try and go back to India. It would mark the 40th anniversary of my overland journey from Istanbul to Delhi. Arriving via the Khyber Pass, between Pakistan and India, my first stop was in Amritsar. I’ll never forget visiting the Golden Temple of the Sikhs and making thanks for my safe passage through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. I’d made it!

I spent the next few months travelling through India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. On the way back from Sri Lanka I decided to go to the British Hill Station of Ootacamund, in the Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu. I was in awe of the ‘Blue Hills’ and vowed I would come back one day.

I was also already regretting that I’d spent most of my time in the northern part of India and left too little time to explore the south. Kerala and Karnataka looked amazing, but I decided to return to Europe. So, in 1978 I flew back from Delhi via an overnight stop in Kabul. The Russians had invaded Afghanistan so I was escorted to my hotel from the airport. This would later herald the ‘beginning of the end’ for backpackers making the overland journey from Europe to India. No longer would we be able to use public transport/ buses freely from country to country, although crossing the borders were always hazardous even in the 70’s, sometimes taking up to a whole day to cross.

So fast forward to 2016. Obviously going ‘overland’ was not an option so I started to look at flights to Bangalore/ Bengaluru. I also checked the best time of the year to visit Southern India. January to May seemed to be the best period to go…and what better time to escape the greyness of a Dutch winter?

On January 4, 2017, I left Amsterdam arriving in Bengaluru (via Delhi) on January 5. I was glad to reach my hotel in the older part of the city which felt familiar. I would notice that many things have changed in India in 40 years, especially with the advent of internet and Bengaluru is one of the so-called Silicon Cities of India, but so many things were still the same.

Settling in after a long journey I decided to go te bed fairly early. However roundabout 2am I was awakened by John phoning. I was absolutely stunned when he informed me that Alan had suddenly died! Alan who I had known since 2001 and often tracked me on my travels making sure I was safe – had only 2 days earlier wished me as always “safe travels. How was this possible??

The following morning, still dazed at John’s news, I decided to take a walk near to the hotel. Within 5 minutes I literally stumbled across a beautiful Buddhist temple, Mahabodhi Loka Shanti Buddha Vihara. At the bookshop, next to the temple, candles were also available so I bought one and lit it for Alan inside the temple. I sat for quite some time thinking about him and praying for “safe travels” on his new journey. I would watch over him for a change.

During the next few days I acclimatised, visited more temples … and planned the next leg of my journey. To Ooty.

Ootacamund/ Udagamandalam

I will never forget travelling to Ooty in the 70’s using the 1-meter gauge mountain railway. It still exists but it is more of a tourist attraction these days. So, choosing a super sleeper bus this time I arrived one early morning in Ooty after the 10-hour journey from Bengaluru. Even the modern Volvo bus took 3 hours to travel the 53-km journey from Mettupalayam to Ooty. The train took 5 hours 😊 But, what a journey through the hills along the precarious roads. I would later see the beautiful tea plantations and the forests of the Nilgiris.

(Nilgiri Mountain Railway, a UNESCO world heritage site)

From Wikipedia, “The origin of the name Udagamandalam is obscure. The first known written mention of the place is given as Wotokymund in a letter of March 1821 to the Madras Gazette from an unknown correspondent. In early times, it was called OttakalMandu. “Mund” is the Anglicised form of the Toda word for a village ‘Mandu’. The first part of the name is probably a corruption of the local name for the central region of the Nilgiri Plateau.

The stem of the name (Ootaca) comes from the local language in which Otha-Cal literally means Single Stone. This is perhaps a reference to a sacred stone revered by the local Toda people. The name probably changed under British rules to Udagamandalam from Ootacamund, and later was shortened to Ooty.

Ooty is situated in the Nilgiri hills. The name meaning blue mountains in Tamil and most other Indian languages might have arisen from the blue smoky haze given off by the eucalyptus trees that cover the area or from the Kurunji flower, which blooms every twelve years and gives the slopes a bluish tinge. Because of the mountains and green valleys, Ooty became known as the Queen of Hill Stations.”

I would find out much more about the TODA later when I visited the Tribal Museum…but I am jumping ahead…

First, I wanted to explore the Nilgiri Hills – and indeed the plantations and forests were as beautiful as I remembered. Only now the residential areas were so built up and sprawling along the roads that much of my idea of viewing a ‘paradise on earth’ slowly evaporated. I joined a day-trip and visited the most touristy places, including a tea plantation.

(A typical view of a tea plantation in the Nilgiri Hills – Morgana 2017)

Here you can also see the slightly blue haze which is always present. See note earlier. Apparently, the Eucalyptus trees are not indigenous to the Nilgiris but were introduced from Australia by the British. Eucalyptus oil is still widely produced as are other essential oils, such as clove oil.

For Gardnerian witches: according to Philip Heselton, David and Com, (Gardner’s governess) owned at least one tea plantation in Ooty. He writes:

“Gerald had kept a rather loose contact with Com and David after he had ‘escaped from her clutches’ in Ceylon. In 1912, David and Com had moved to the Nilgiri Hills in southern India and had acquired several tea estates, including Ripple Vale and Ibex Lodge Hill, the most famous of which was the Nonsuch Estate, which still exists.” letter from Gillian Hodges to the author 5 May 2008)

I asked the taxi driver who drove me around to the Toda village etc if he knew of the estates. He also confirmed that the Nonsuch estate still exists. He was willing to take me there but that it was a long way from where we were at that moment, so I declined his offer.

However, the most impressive and to me the most interesting places were the ones I visited on my own. As ever it starts with a walk… in this case through the Ooty centre.

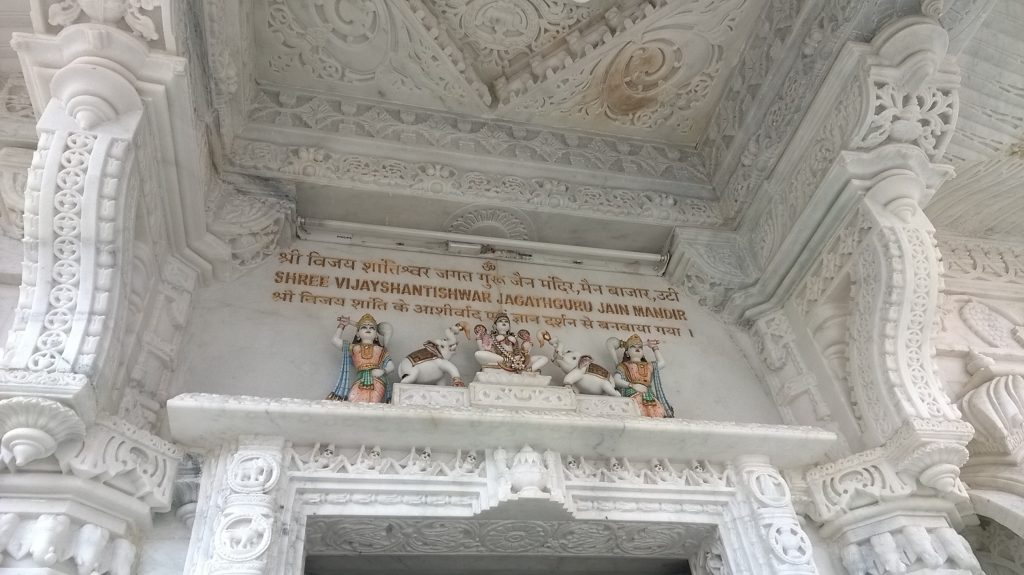

Perhaps the most beautiful temple I saw this trip was the Jain Temple in Ooty. Completely made of dazzling white marble the intricacy of the stone work was like lace work. Of course, I couldn’t take photos inside but I was able to take these photos outside. The stone work inside was just as intricate. The atmosphere was so serene and calm that I spent some time thinking of Alan.

On the same day that I saw the Jain Mandir I also witnessed a celebration. From a distance, I could hear chanting… then I saw a large circle of mainly men moving clockwise.

Then this small lady tapped me on the shoulder and told me that this was a TODA celebration.

Toda lady – wearing the typical Toda toga or ‘putkuli’ and with the typical hairstyle of ringlets. Morgana 2017)

She told me that they visited the market in Ooty every week to sell milk. She also invited me to go and visit the Toda village. I remember seeing a day trip advertised to visit the “Tribal village & Tribal Museum” and decided to do it a couple of days later. In between times I looked up my notes about Tribal culture in India and read up a little bit about the tribes in the Nilgiri Hills. (See the earlier reference about the name Ooty and the Toda).

Although my interest in India was inspired by the stories from the Bhagavad Gita and Hinduism, when I visited in the 70’s I soon found out that there were also many people who were classed as ‘Tribal’. I would later see many of the folkloric influences in Wicca were akin to the animistic practices of indigenous people.

I was therefore more than curious to find out more about the Toda. Their dress and the lady’s hairstyle (the ringlets) were so very different from the Hindus and so on. Hiring a private taxi, I first went to the Toda village. Today the Indian Government are encouraging the Toda – about 800 in total spread, over various hamlets, to live in houses made of concrete. The traditional house style resembling a beehive or barrel, is still emulated but is gradually being replaced by ‘normal’ oblong shaped houses.

So, who are the Toda and what do they believe?

There are several conflicting theories about the origin of the Toda. There is an interesting article by Anthony R. Walker, “The truth about the Todas, On the origins, customs and changing lifestyle of the tribal community in the Nilgiris”.

He writes:

“SINCE the early 19th century, a great deal of misinformation has been generated about the origins and socio-economic institutions of the Toda people of the Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu. But, for over a century now, following the arrival in the Nilgiris in 1901 of Cambridge University scholar W.H.R. Rivers, much painstaking anthropological and linguistic research has been accomplished. This has resulted, inter alia, in such books as Rivers’ The Todas (1906), M.B. Emeneau’s Toda Songs (1971), Ritual Structure and Language Structure of the Todas (1974) and Toda Grammar and Texts (1984), and this writer’s The Toda of South India: A New Look (1986) and Between Tradition and Modernity and Other Essays on the Toda of South India (1998).

Despite this solid body of research, it seems that some writers have no qualms about propagating arrant nonsense in the name of information. As it is said, “a good story travels a thousand miles while the truth decides which pair of socks to wear”. Unfortunately, a “good story” on the Internet travels even faster, and spreads more widely than ever before.

A particularly galling assemblage of ancient errors and modern absurdities about the Toda people is the anonymously written article “The Todas: Pagan Rituals, Primitive Rites”, posted on indiaprofile.com, apparently a site designed to promote tourism and disseminate information about India’s people and their cultures.” (For the full text of this article I have included the website link under ‘references’.)

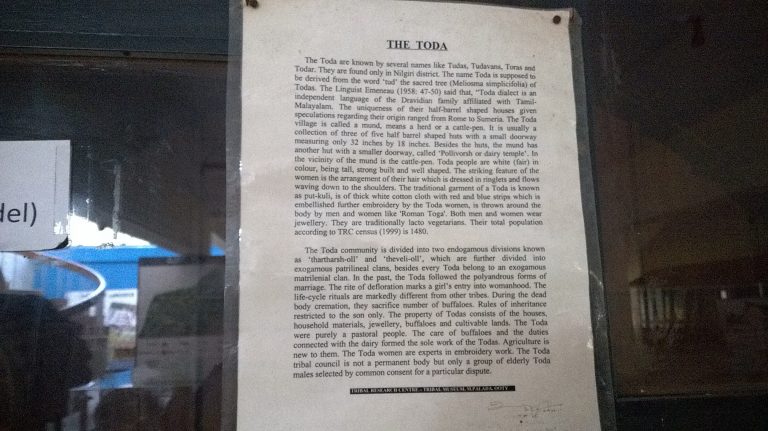

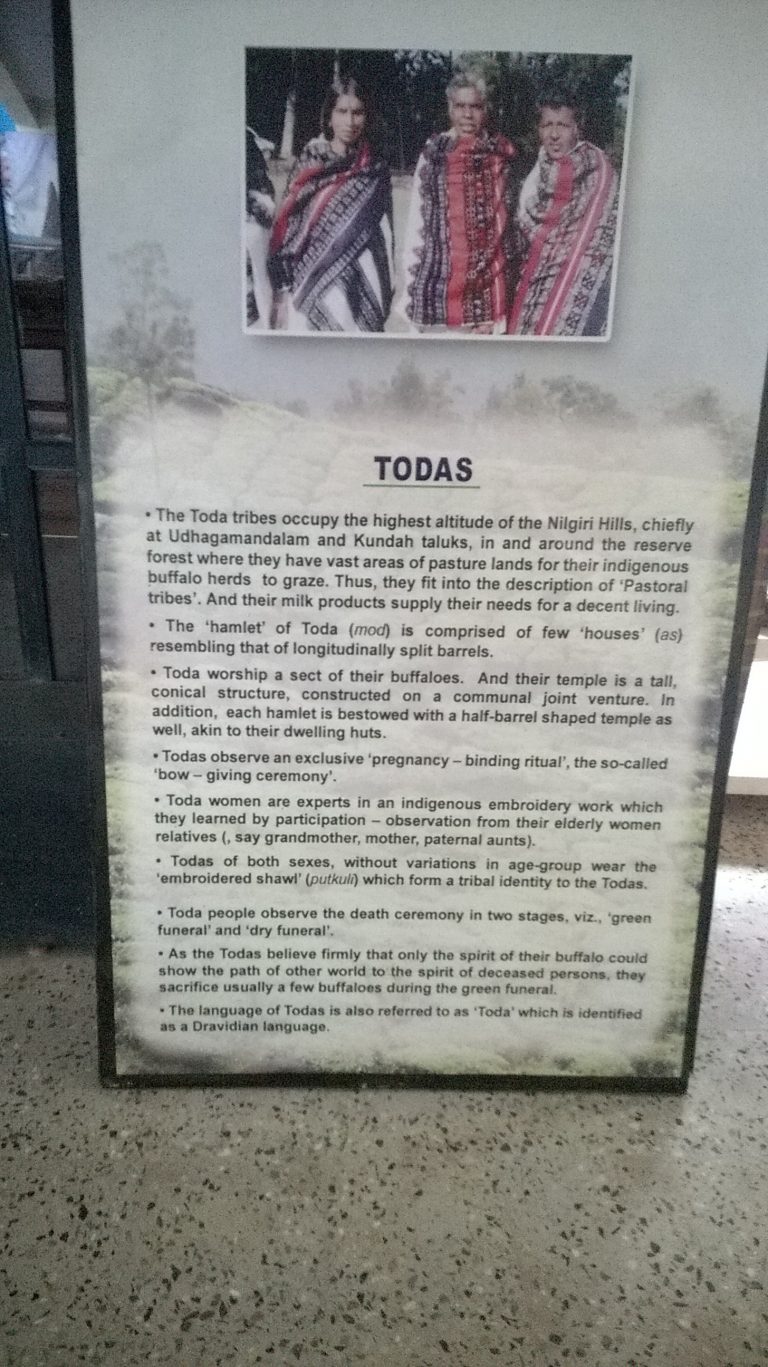

Here are a couple of the information sheets I saw at the Tribal Museum in Muthorai Palada, Ooty.

The Tribal Museum, although not the easiest place to get to, is most definitely worth a visit with much information and artefacts about several different tribes.

Coming back to the Toda. As a pastoralist tribe, the Toda revere the Buffalo, especially the She-Buffalo.

A.R. Walker, “Central to Toda religion are sacred places associated with the community’s dairy-temples, their related buffalo herds, appurtenances and priesthood. These are not simply places where gods reside, but are themselves divine, the “gods of the places”, the Todas say. Entry into a Toda dairy is prohibited to all but Toda males of appropriate ritual status. But the dairy-temples are not “secret”; many are located within the munds themselves.”

From the information sheet, 2. “Toda worship a sect of their buffaloes. And their temple is a tall conical structure…”

When I visited the village, I was allowed to enter the meadow (first taking off my shoes of course) and to go right up to this strange conical structure. Normally women are not even allowed in the vicinity of this temple. Made of layers of grass-like fibre it towered about 12 meters. Apparently, the fibre was not local and was brought from afar especially for the temple. There was a single entrance. I was told that there was a special ceremony held only once every 12 years. The Priest who officiated was called the “Holy Milkman”.

In the village – mund– was another temple which appeared to be used regularly:

(A ‘regular’ Toda Temple – Morgana 2017)

Even in this ‘regular’ temple women were prohibited from entering. There was however another structure which looked as if it was a more communal meeting place where I suspect ceremonies like the one I had seen a couple of days earlier in Ooty were performed.

(A single column, stone, in the communal area of the Toda village – Morgana 2017)

This single column reminded of what I had read about the name Ottacamund, “The stem of the name (Ootaca) comes from the local language in which Otha-Cal literally means Single Stone. This is perhaps a reference to a sacred stone revered by the local Toda people.”

Today the Toda earn their living by selling milk and embroidered cloths. At sunrise the Toda priest, the “Holy Milkman” offers his morning prayers and milks the sacred buffalo. Meanwhile the women and girls help milking the domestic buffaloes. They also gather together to curl their hair into the distinctive ringlets and to embroider their shawls/putkuli. The embroidery motifs are inspired by nature and their daily duties. The Sun and Moon but also reptiles, animals (rabbits) and of course the horns of the buffaloes are used.

“The fabric used is coarse bleached half white cotton cloth with bands; the woven bands on the fabric consist of two bands, one in red and one band in black, spaced at six inches. Embroidery is limited to the space within the bands and is done by using a single stitch darning needle. It is not done within an embroidery frame but is done by counting the warp and weft on the fabric which has uniform structure by the reverse stitch method. To bring out a rich texture in the embroidered fabric, during the process of needle stitching, a small amount of tuft is deliberately allowed to bulge. Geometric pattern is achieved by counting the warp and weft in the cloth used for embroidery.”

Recently the Toda embroidery was awarded “Geographical Indication/GI status. This means that prized goods are designated by their specific geographical location and protected by law.

(Toda embroidery awarded GI status – The Hindu, March 2013)

“Programme Coordinator of the Foundation T. Samraj said that henceforth only those registered with the three organisations could deal with Toda embroidery. The embroidery was unique in many ways and out of a total population of around 1600 only about 300 to 400 Toda women still practiced the art.

Pointing out that the art was several centuries old, members of the community said that in their dialect embroidery was called, ‘pukhoor’. While the most famous Toda embroidered item is the shawl called ‘pootkhuly’, over the years they have started making many things like wall hangings, table mats, shoulder bags, ladies and gents tops and shopping bags. While over the years the tradition has been passed down generations (from mother to daughter), during the past few years organisations such as the Tribal Cooperative Marketing Development Federation of India had been facilitating training programmes.” (The Hindu newspaper, March 2013)

Looking at some of the Toda motifs I was reminded of the embroidery I knew from the Balkans and Slavic countries. Suddenly home was very close by 😊

References:

Ooty: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ooty [Accessed July 23, 2017]

Nilgiri Mountain Railway, a UNESCO world heritage site: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ooty#/media/File:NMR_up_train_at_Kateri_Road_05-02-28_04.jpeg [Accessed July 23, 2017]

Philip Heselton “Witchfather, A Life of Gerald Gardner, Volume 1, Into the Witch Cult” Page 105/ letter from Gillian Hodges to the author 5 May 2008)

ANTHONY R. WALKER – THE TRUTH ABOUT THE TODAS, On the origins, customs and changing lifestyle of the tribal community in the Nilgiris: http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2105/stories/20040312000206600.htm [Accessed July 23, 2017]

This is the article which A.R.Walker disputes: “The Todas – Pagan Rituals, Primitive Rites”:

http://www.indiaprofile.com/lifestyle/todas.htm [Accessed July 23, 2017]

Information about Tribal Museum, Ooty: http://www.eooty.com/tourism/sightseeing/tribal-museum.php [Accessed July 26, 2017]

Toda embroidery: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toda_Embroidery [Accessed July 26, 2017]

http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-tamilnadu/toda-embroidery-gets-gi-status/article4556982.ece [Accessed July 26, 2017]

Very interesting, Morgana! Beautiful pictures too – Greets, Luna Verde – Cristina <3

Thanks Luna! In my next ’tale of India’ I want to talk about Muziris, the ancient port.