This is a slightly edited text of a talk I gave at the Australian Wiccan Conference, Canberra, September 1992 and you might wonder why I have chosen to republish this after more than 20 years. In fact I had all but forgotten it when I stumbled upon the text whilst moving files from my old PC to my new one. Curiosity piqued I read it and as I did so, I remembered why I had decided on this topic for my talk at Canberra in 1992. Some of the examples – particularly those of the “ritual child abuse” scam in the 1980s and 1990s – have passed into history and maybe should be left to lie there; but the phrase that kept repeating on loop in my head as I re-read this talk is that those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.

Persecution and fundamentalism present as big a danger to us in the 21st century as they have always done in the past. At one point in the talk I commented that the only thing that has really changed is our ability to communicate more widely and more effectively than in the past and that comment was made in 1992, before the advent of the world wide web and mass communication on a scale impossible to envisage throughout most of humanity’s history.

On 12th September 2010, I was a member of a panel at the ‘Day for Gerald Gardner’ at Conway Hall in London and a member of the audience asked the panel: “what do you consider the greatest threat facing us in the modern world?” I had no hesitation when it came to my turn to comment and said, “fundamentalism”. When asked if I meant Islamic or Christian fundamentalism or Wiccan, I said, “all fundamentalism.” I may be simplistic but in my view, the narrow-minded certainty expressed by fundamentalism in any of its guises is the biggest threat we face today, and indeed have always faced.

Witch 1643

In Australia recently, the government made a formal (and extremely eloquent) apology to those children and their families who in the past, were torn apart by well-meaning interception in removing babies from their mothers. Only an absolute certainty in being right could have led to such an occurrence in the first place; a mindset that was so sure of itself that even witnessing scenes of trauma resulting from forcibly removing children from their families was considered to be inconsquential.

Examples of the consequences of a fundamentalist mind-set are everywhere and it would be too depressing to highlight more than one example here. Nevertheless, this prevalence of absolute certainty in being right is the main reason that I thought it might be time to dust off this talk and give it another outing. The original talk was supported by slides (yes, pre-powerpoint days!) and although I still have them, I have yet to transfer them to jpg files so have used similar alternative images where appropriate.

To begin, an example of religious persecution:

“I am told that, moved by some foolish urge, they consecrate and worship the head of a donkey, that most abject of all animals. This is a cult worthy of the customs from which it sprang! Others say that they reverence the genitals of the presiding priest himself, and adore them as though they were their father’s… As for the initiation of new members, the details are as disgusting as they are well-known. A child, covered in dough to deceive the unwary, is set before the would-be novice. The novice stabs the child to death with invisible blows; indeed, he himself, deceived by the coating of dough, thinks his stabs harmless. Then – it’s horrible! – they hungrily drink the child’s blood, and compete with one another as they divide his limbs.

Through this victim they are bound together; and the fact that they all share the knowledge of the crime pledges them all to silence. Such holy rites are more disgraceful than sacrilege. It is well-known too what happens at their feasts…. On the feast day they forgather with all their children, sisters, mothers, people of either sex and all ages. When the company is all aglow from feasting, and impure lust has been set afire by drunkenness, pieces of meat are thrown to a dog fastened to a lamp. The lamp, which would have been a betraying witness, is overturned and goes out. Now, in the dark so favourable to shameless behaviour, they twine the bonds of unnameable passion, as chance decides. And so all alike are incestuous, if not always in deed, at least by complicity; for everything that is performed by oneof them corresponds to the wishes of them all… Precisely the secrecy of this evil religion proves that all these things, or practically all, are true.” (Minucius Felix: Octavius)

Although the language is not modern, the description of the practices could have come straight from any modern tabloid or blog. And this is the point that I wish to make; the facts of persecution have not changed in almost 2,000 years, for that piece was written in the 2nd century AD. Moreover, the religion it condemns is Christianity, not Paganism, for Paganism at that time was the dominant state religion. In fact the author is a Christian apologist, and is attempting to rebuke what he sees as unfair criticism, by parodying the offences which Pagans accuse Christians of perpetrating.

Persecution of religious minorities is quite simply that; it is persecution by a large body of people, generally those who represent “society”, against a smaller one generally comprised of those who have either rejected, or for one reason or another, fall outside of the social “norm”.

Let us look at the medieval picture of the witch; society’s scapegoat par excellence. Often shown as an old, ugly woman, most likely poor, and most likely on the fringe of the society in which she lives. This is the stereotype of the witch. We know it is false; we know it has no basis in fact; however, it became an integral part of the mindset of medieval Europe, and through fairy tales, drama and literature, and more latterly, cinema, the media and television, it has remained an integral image in modern society. One has only to look to Roald Dahl’s “Witches”, or Frank Baum’s “Wizard of Oz”, for proof of this. It came as a surprise to me to learn that “The Wizard of Oz” was in fact a deliberate propaganda exercise, released just at the beginning of World War II. If you remember, the magic words are: “There’s no place like home”, and where was “home”? Kansas, the heartland of America.

When looking at medieval persecution of heresy, the waters are muddied by the many different causes and effects that permeate the whole matter. There was no single cause, and no single victim. It is a fact that far more women than men were persecuted; there are a number of reasons for this, not least that throughout this period, Europe was engaged in one war after another, most notably The Crusades, and men were in rather short supply. There were also several epidemics of the plague, not to mention other diseases such as dysentery and cholera, which in the Middle Ages were sure killers. Another reason is the rampant misogyny which, begun with the earliest Christians, has permeated their theology ever since:

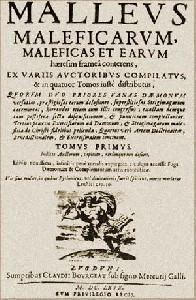

(Malleus Maleficarum)

“What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted in fair colours… The word woman is used to mean the lust of the flesh, as it is said: I have found a woman more bitter than death, and a good woman more subject to carnal lust… [Women] are more credulous; and since the chief aim of the devil is to corrupt faith, therefore he rather attacks them [than men]… Women are naturally more impressionable… They have slippery tongues, and are unable to conceal from their fellow-women those things which by evil arts they know…. Women are intellectually like children… She is more carnal than a man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations… She is an imperfect animal, she always deceives…. Therefore a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft…. Just as through the first defect in their intelligence they are more prone to abjure the faith; so through their second defect of inordinate affections and passions they search for, brood over, and inflict various vengeances, either by witchcraft or by some other means…. Women also have weak memories; and it is a natural vice in them not to be disciplined, but to follow their own impulses without any sense of what is due… She is a liar by nature… (Malleus Maleficarum, edited by Jeffrey Russell).

It is easy to comprehend the persecution of women when one is confronted with such obvious hatred and fear of the gender. But perhaps the most powerful impetus of the witch trials era is one often present in the trials; pursuit of power or wealth. For an example we can look to Gilles de Rais, who as the wealthiest man in Europe (as well as Joan of Arc’s Captain), was a prime victim for a charge of heresy. Found guilty, his lands, properties and wealth were confiscated by his accusers. A telling fact after his executive was that he was buried on consecrated ground in the Churchyard; normally forbidden to heretics. In “The Encyclopaedia of Witchcraft and Demonology”, Russell Hope Robbins says:

“At first, Gilles dismissed their accusations as “frivolous and lacking credit”, but so certain were the principals of finding him guilty that on September 3, fifteen days before the trial began, the Duke [John V of Brittany] disposed of his anticipated share of the Rais lands. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to place any credence in the evidence against him, among the most fantastic and obscene presented in this Encyclopaedia.”

Charges included the now obligatory conjurations of devils and demons; Satan, Beelzebub, Orion and Belial are mentioned by name. The charges also included geomancy, human sacrifice and paedophilia and it is probably the accusations of paedophilia that most people who have heard of Gilles de Rais remember.

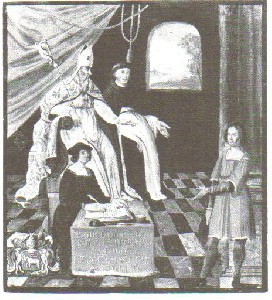

(Gilles de Rais (left) and The Trial of Gilles de

Rais (right). The painting is by an unknown

artist c. 1835 — no original painting survives.

Far right: Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia),

unknown artist.

There were not many who had the wealth of Gilles de Rais, but even in a small parish the meanest property was eagerly seized and the witch hunts became a profitable business. The victims were even required to pay for the fuel upon which they were burnt. But the laws were not consistent throughout Europe and in some areas, if the victim confessed, then his or her property could not be confiscated, but was inherited by the next of kin. Extant records show that many of the accused were tortured to the point were they would admit to being anything demanded of them, although technically, they were only allowed to be tortured once. This is why trials records specify that the torture was “continued”.

Although many heretics were women, a great many men were also taken, tortured, and put to death. This is a letter from one such victim at the notorious Bamberg in Germany; a poignant epitaph to one of Europe’s most hideous crimes:

Many hundred thousand good-nights, dearly beloved daughter Veronica. Innocent have I come into prison, innocent have I been tortured, innocent must I die. For whoever comes into the witch prison must become a witch or be tortured until he invents something out of his head – and God pity him – bethinks him of something.

I said: “I have never renounced God, and will never do it – God graciously keep me from it. I’ll rather bear whatever I must.”

And then came also – God in highest heaven have mercy – the executioner, and put the thumbscrews on me, both hands bound together, so that the blood spurted from the nails and everywhere, so that for four weeks I could not use my hands, as you can see from my writing. Thereafter they stripped me, bound my hands behind me, and drew me up on the ladder. Then I thought heaven and earth were at an end. Eight times did they draw me up and let me fall again, so that I suffered terrible agony.

All this happened on Friday June 30th and with God’s help I had to bear the torture. When at last the executioner led me back into the cell, he said to me: “Sir, I beg you, for God’s sake, confess something, whether it be true or not. Invent something, for you cannot bear the torture which you will be put to; and, even if you bear it all, yet you will not escape, not even if you were an earl, but one torture will follow another until you say you are a witch.”

The author of this letter, Johannes Junius, did indeed confess to being a witch, and in August of 1628, was burned at the stake. He managed to send his final letter to his daughter, which ended by saying:

“Dear child, keep this letter secret, so that people do not find it, else I shall be tortured most piteously and the jailers will be beheaded. So strictly is it forbidden… Dear child, pay this man a thaler… I have taken several days to write this – my hands are both crippled. I am in a sad plight. Good night, for your father Johannes Junius will never see you more.”

This letter describes more accurately than any historical treatise just how uncompromising the ecclesiastical courts were in their hunt for heretics. Witches, of course, were only one kind of heretic.

I mentioned earlier that there are many causes and effects to the period that is commonly referred to as ‘The Burning Times’ or the Great Witch Hunt. It is often assumed that Christianity has been the dominant western religion for 2,000 years. This is not so. The death of Christ may have heralded a new religion, but there was certainly not an immediate conversion of the world to Christianity. Parts of Scandinavia remained wholly Pagan until as late as the 12th century. The British Isles and mainland Europe were converted to Christianity over a lengthy period covering mainly the 4th to 9th centuries. Some parts have never truly been converted and with the opening up of the Eastern bloc countries, we are now re-discovering a wealth of Pagan tradition and folklore that has been hidden for hundreds of years: initially from the invading Christian missionaries, and then later from the various communist regimes.

As the new religion of Christianity began to spread, many different sects and cults appeared within its ranks. The Pope was the nominal head, but rarely was he a person of spiritual purity and ascetic tastes; the political scene in Rome has always been cut-throat and devious. The enormous wealth and power controlled by the Pope was an incentive to the most grasping and corrupt of men at that time to aspire to the Papacy. Pope Alexander VI (1492) is a superb example of the type who made it to Europe’s foremost political seat of power: otherwise known as Rodrigo Borgia; father of Cesare, Juan, Lucrezia and Jofre, and supreme commander of a private army that any modern dictator would envy.

Because of their sumptuous lifestyle, their obvious disregard and contempt for vows of poverty and chastity, and their abuse of the spiritual authority invested in them, many spiritually inclined Christians rejected the Catholic Church and instead followed leaders who lived simple, ascetic lives in accordance with the teachings of Christ. Some of these sects became very popular and were soon perceived by the Pope as a threat to his status and power. It has been suggested that the witch trials were a direct result from the persecution of these sects. A discussion of the different sects falls well beyond the scope of this talk but briefly, the main thrust was against the Cathars or Albigensians, and the Waldensians (Vaudois), and it was their persecution which gave rise to the legal machinery that developed into the Inquisition and the so-called witch hunts.

It began with Pope Lucius III and the emperor, Frederick I Barbarossa; they met at Verona in 1184, and issued the decree “Ad abolendam”, which excommunicated sects like the Cathars and Waldensians and laid down the procedures for ecclesiastical trial, after which the accused would be handed over to the secular authorities for punishment. The punishment decreed was confiscation of property, exile, or death. By the 12th century, burning had already become the established means of execution for heretics, and so this became enshrined in law.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Dominican Order of Friars was established and its members were instructed by the Pope to investigate and prosecute heresy. From this simple beginning grew the awesome machinery of the Inquisition, which although never aimed particularly at witches, became a byword for terror in parts of Europe.

As you can see, the motives for the heresy persecutions were not to stamp out Paganism, although that was certainly a by-product, but to remove the threat of any competition to the power of the Church (and thus to the Pope), in Rome. And the greatest threat came from other “Christian” sects, not the Pagans. The change from an accusatory to an inquisitorial process became established, and the legal machinery which allowed – indeed encouraged – psychopaths and religious zealots to persecute at will, was in place.

Have you got a neighbour who annoys you? plays loud music, or who keeps their smelly refuse next to your garden fence? Now your recourse is to the local council or the police; in the Middle Ages, you simply denounced the offender as a witch or heretic, and let the Church deal with them for you. Not only did it cost you nothing, if you were lucky, you might also inherit their property.

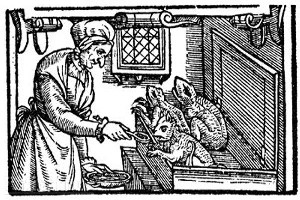

(Elizabethan era witchcraft)

For once you were taken as a witch or a heretic, there was little chance of escape. Certainly some victims were pardoned and released, but the vast majority were not so lucky. When you consider the style of questioning, this is not surprising:

1 How long have you been a witch?

2 Why did you become a witch?

3 How did you become a witch and what happened on that occasion?

4 Who is the one you chose to be your incubus? What was his name?

5 What was the name of your master among the evil demons?

6 What was the oath you were forced to render to him?

21 What animals have you bewitched to sickness and death, and why did you commit such acts?

22 Who are your accomplices in evil…?

24 What is the ointment with which you rub your broomstick made of…?

This set of questions came from Lorraine, and was used consistently throughout the three centuries of the main persecutions. Bearing in mind that the accused had to answer – no answer at all, or a denial, was tantamount to guilt – you can see how easily the composite picture of the witch evolved. As Rossell Hope Robbins says: “The confessions of witches authenticated the experts, and the denunciations ensured a continuing supply of victims.

(Witches dance)

Throughout France and Germany this procedure became standardised; repeated year after year, in time it built up a huge mass of ‘evidence’, all duly authorised, from the mouths of the accused. On these confessions, later demonologists based their compendiums and so formulated the classic conceptions of witchcraft, which never existed save in their own minds.”

It is also rather disturbing to discover just how important individual religious zealots appear to have been in the persecutions. Rather like today, where a crusading tele-journalist, or evangelical vicar, can cause untold harm to innocent people. Without exception, these accusations are by those with an unhealthy mania against anyone whose theology or practices differ from their own. In the words of one modern evangelist: “if you’re not fighting and winning, you’re losing.”.

Conrad of Marburg, described by Norman Cohn as, “a blind fanatic”, was a severe and formidable persecutor. As confessor to the young 21 year-old Countess of Thuringia, he would trick her into “some trivial and unwitting disobedience, and then have her and her maids flogged so severely that the scars were visible weeks later”. (Cohn). Conrad became Germany’s first official Inquisitor, and his zeal in denouncing heretics was unsurpassed. Another Conrad, a lay-Dominican Friar, and his sidekick Johannes, were also vigorous in denouncing heretics. As they moved from village to village, they claimed to be able to identify a heretic by his or her appearance, based on nothing but their own intuition. They were responsible for the burnings of many people, and said, “we would gladly burn a hundred if just one among them were guilty”. (Annales Wormantiensis).

(Mother Shipton)

Their comment about appearance is an important one; as we saw earlier, the stereotype of the witch hasn’t changed much in hundreds of years. We know it is false; we know that it exists only in the imagination of the persecutors, and yet how powerful and enduring this stereotype has proven to be.

If we think about this stereotype, what images do we conjure up? An old woman – occasionally an old man; or perhaps a young and alluring temptress? Flying through the air on a broomstick; worshipping a devil, often in the form of a goat; trampling upon the sacred symbols of Christianity; and of course our old friend the Sabbat, with its practices of sexual license, debauchery, drunkenness and ritual murder; the latter often of children.

But persecution does not restrict itself to witches; the similarities between this stereotype and that of the Jew are obvious: Jews have been persecuted throughout their history, but it is interesting to compare some aspects of their persecution with that of witches.

In the 12th century, the word ‘Synagogue’ was used for the first time to describe the meeting place of heretics. Professor Russell says that: “This usage, obviously designed to spite the Jews, was common throughout the Middle Ages, being replaced only towards the end of the 15th century by the equally anti-Jewish term ‘sabbat’.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica says on the subject of Jewish persecution that: “To reinforce racial and religious prejudice, the preposterous ritual murder accusation became common from the 12th century.” The third and fourth Lateran Councils had already prohibited gentiles from entering Jewish service, or being employed by Jews, and further ordered that Jews should wear a distinctive badge, and live only in Jewish settlement areas. This of course was the beginning of the ghetto.

As we have seen though, the ritual murder accusation was already over a thousand years old before it was used against either the Jews or heretics and witches. Most people know of the expulsion of Jews from Spain in the 15th century, but perhaps not so commonly known is that for about 200 years prior to the expulsion, the Jews had been massacred and persecuted. Indeed, it was against the Jews that the infamous Spanish Inquisition of the 15th century was directed. The persecution of Jews in 20th century Europe is too well-known to require further comment here, but perhaps a few comments about its encouragement would be useful.

We are discussing persecution in this talk, and how persecution is manifested. Throughout history, the written word has been invaluable as a means of spreading propaganda. Even in the Middle Ages the crimes of the heretic were publicised by records of trials, where the confessions were made known to the general public. The infamous ‘Malleus Maleficarum’ became highly influential in Europe mainly because its publication coincided with the introduction of printing. It had little effect in England because no English translation was available until 1928. This fact alone demonstrates the power of the written word.

In medieval Europe, a pamphlet describing the crimes of a convicted heretic would be pinned to a post in the town square, and those who could not read had it read to them. In 20th century Europe, pamphlets were still used by one group to spread lies about another. In the 21st century this technique is still used with very great success for the lies that are circulated are often far more scandalous than the reality and once out there, they take on a life of their own.

An example: soon after the launch of the Pagan Alliance, Sydney radio 2MMM broadcasted a news story about the sexual abuse of children by occultists and witches. The Pagan Alliance responded immediately and provided the station with copy documents and news clippings from Britain, proving the story to be without foundation and a scheme by Christian fundamentalists to discredit Pagans. The news editor and chief journalist were impressed by the material and agreed that they had been used by the fundies. However, they refused to broadcast a retraction because it would be “old news”. So, the damage had been done and the fundamentalists achieved their objective.

This technique was used with very great effect in the early part of the 20th century, with the circulation of a pamphlet called, ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’. This purported to be, “an account of the World Congress of Jewry held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, during which a conspiracy was planned by the international Jewish movement and the Freemasons to achieve world domination.” (‘The Occult Conspiracy’ by M Howard).

German nationalists made very great use of the Protocols, which it was claimed were “smuggled out of Switzerland by a Russian journalist who had placed the documents in the safe keeping of the Rising Sun Masonic Lodge in Frankfurt.” (Howard). They were widely disseminated and writing in “Mein Kampf”, Hitler “denounced the Jews as agents of an international conspiracy devoted to world domination…”. (Howard) We all know what happened next.

The point is that although the Protocols were confirmed as a fraud in 1921, they continued to have an effect and once published, could not effectively be retracted. This is the aim of today’s fundamentalist, who believes that if he or she throws enough dirt at their opponents (basically anyone who does not agree with their uncompromising version of their religion or culture), then some will stick and the battle will be won. This strategy has been used for thousands of years to persecute minorities, and has always been successful. The formula is simple: discover what most people fear most and then accuse your enemies of practising it. It is an interesting comment on humanity that the fears that occur time and time again are consistent: conspiracy, buggery, paedophilia, sacrifice (human and animal), sexual license, drunkenness and feasting. More specific charges relating to a pact with a devil or desecrating sacred objects are additions to these core accusations.

A further interesting aspect is that there is a long history of accusations being made by children. It has been widely recorded that Hitler’s Youth Army required children to spy upon their parents and report any indiscretions; in the 1980s and 1990s social workers in Britain used an identical process for identifying Pagan parents. Children were asked about what their parents did and leading questions were commonly used.

In medieval England, there were many occasions where children’s evidence (sic) was used to convict witches. ‘The Leicester Boy’, ‘The Burton Boy’ and ‘The Bilson Boy’ were a few of many who claimed to be bewitched by witches. Eventually proven to be a fraud, at least ten women died as a result of the accusations of The Leicester Boy,and the Burton Boy caused the death of at least one of the women whom he accused. In the 17th century a number of women were executed on the allegations of hysterical children, even though fraud was often discovered during the course of the trial. It is a fact that the delusions of delinquent or disturbed children were often used by judges to confirm their own prejudices.

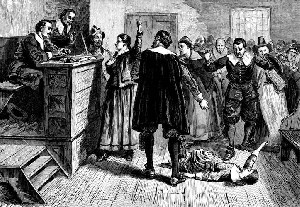

Salem (1692) is probably the best known of all the cases where children were the chief accusers. Although in fact, the children were more like young adults, with only one under the age of ten and most in their late teens or early twenties. However, as the panic grew, a great many more were sucked into the web of lies, and Martha Carrier was hanged on the evidence (sic) of her seven year-old daughter. At the height of the hysteria almost 150 people were arrested; 31 were convicted, and 19 hung. Some others died in jail and others were reprieved. As was common in Europe, the accused were required to pay their expenses whilst in jail, even if they were subsequently found innocent. Sarah Osborne and Ann Foster both died in jail and costs of £1 3s 5d and £2 16s 0d respectively were demanded before the bodies would be released for burial.

The chief of the accusers, Ann Putnam, confessed fourteen years later that the whole thing was a fraud. In 1697 the jurors publicly confessed they had made an error of judgement, and ten years after the executions, Judge Samuel Sewallevidence “confessed the guilt of the court, desiring to take the blame and shame of it…”. By then of course it was too late for those who were dead, or whose lives had been destroyed by the accusations.

(Salem Witch trial)

But we are getting ahead of ourselves here, for Salem is the last of the great witch trials, coming as it does towards the end of the 17th century.

I mentioned earlier that in Continental Europe, the heresy trials appeared to arise from the persecution of the Christian sects of the Bogomils, Cathars, Albigensians, and others such as the Jews, Waldensians, and even the Knights Templars. The stereotype of the witch was compounded from many different sources, and gradually became the composite figure of the shape-shifting hag, who flew through the air on a broom, and flung her curses at all and sundry.

The concept of the pact with the devil existed as early as the 8th century, and as we have seen, sexual license, buggery and ritual sacrifice have long been seen as activities supposed to be practised by those outside of society’s norm, whether they be Christian or Pagan. During the 9th century, shape-shifting, maleficia and the incubus/succubus became more commonly reported and by the 10th century, the idea of nocturnal flight was established. Published in 906, the Canon Episcopi described how some women were deluded in the belief that at night they could fly behind their Goddess, Diana (Holda or Herodias):

“Some wicked women are perverted by the Devil and led astray by illusions and fantasies induced by demons, so that they believe they ride out at night on beasts with Diana, the pagan goddess, and a horde of women. They believe that in the night they cross huge distances. They say that they obey Diana’s commands and on certain nights are called out in her service…”

In his fascinating book, ‘Ecstasies: Deciphering The Witches’ Sabbath’, Carlo Ginzburg suggests that the gathering and the night flight are based on genuinely ancient shamanic practices and there are echoes here to Maddalena’s story recounted by Leland in ‘Aradia: Gospel of the Witches’:

“Once in the month, and when the moon is full, ye shall assemble in some desert place, or in a forest all together join to adore the potent spirit of your Queen, my mother, great Diana”.

In 1012, Burchard’s Collectarium was published: the first attempt to assemble a book of Canonical Law. Book number 19 of this vast collection was called the Corrector and chapter five deals with various sins penances. It enshrines in law the notion of night flight, together with murder and the cooking and eating of human flesh. Although both the Canon Episcopi and Burchard’s Corrector are specific in attributing the powers of flight to witches, it is not until 1280 that the first picture of a witch riding upon a broom appears. This is found in Schleswig Cathedral.

In Orleans in 1022, the first burning occurred. The victims were accused of, “holding sex orgies at night in a secret place, either underground or in an abandoned building. The members of the group appeared bearing torches. Holding the torches, they chanted the names of demons until an evil spirit appeared. Now the lights were extinguished, and everyone seized the person closest to him in a sexual embrace, whether mother, sister or nun. The children conceived at the orgies were burned eight days after birth, and their ashes were confected in a substance that was then used in a blasphemous parody of holy communion.”

The 14th century saw a steady growth in the number of accusations and trials, and by the 15th century, the idea of the Devil’s (or Witch’s) mark had become established. So too was the idea of a flying ointment and a consistent image of The Devil became common in trials literature.

The Papal Bull of 1484, Summis Desiderantes Affectibus, and then two years later, publication of the Malleus Maleficarum, further established the “crime” of witchcraft as a heresy, and confirmed Papal support for its eradication. This infamous work – The Malleus Maleficarum or Hammer of the Witches – was incredibly influential in establishing a code of practice by which witches were to be denounced, tried, convicted and executed. The third part of the book describes how to deal with one who will not confess to the charges:

“But if the accused, after a year or other longer period which has been deemed sufficient, continues to maintain his denials, and the legitimate witnesses abide by their evidence, the Bishop and Judges shall prepare to abandon him to the secular Court; sending to him certain honest men zealous for the faith, especially religious, to tell him that he cannot escape temporal death while he thus persists in his denial, but will be delivered up as an impenitent heretic to the power of the secular Court.

It is also in this section that our friendly Dominican monks refer to, “witch midwives, who surpass all other witches in their crimes… And the number of them is so great that, as has been found from their confessions, it is thought that there is scarcely any tiny hamlet in which at least one is not to be found.”

Despite its incredible influence in Europe, as noted above the lack of an English translation until modern times meant that the Malleus had little effect in England, Wales or Ireland, where witchcraft accusations and trials were very different to those of the continent and Scotland. In fact Wales and Ireland seemed to escape from the witch persecutions almost entirely, with very few trials and even fewer executions.

Although many laws have been enacted in England against witchcraft, there has never been anything like the hysteria about witches common in mainland Europe and Scotland. The earliest known person accused of sorcery in England was Agnes, wife of Odo, who in 1209 was freed after choosing trial by ordeal of grasping a red-hot iron. There are certainly earlier mentions of witches, for example in the ‘De Gestis Herwardis Saxonis’, where Hereward’s wife is identified as a woman skilled in the mechanical arts and Julia of Brandon as a witch employed by the Normans to curse the English, but these are not trial records and as far as history records, Hereward’s wife was honoured rather than executed.

Indeed until 1563, commoners accused of witchcraft in England met light (if any) punishment. Those of noble birth were treated rather more severely, as the crime could easily be one of treason, and any action which implied a threat to the monarch was treated very seriously indeed. This resulted in the charge of witchcraft being used to remove political opponents with great expediency. There were certainly laws against the practice of witchcraft or sorcery: Alfred the Great (849-899 AD), King of Wessex and overlord of England, decreed the death penalty for Wiccans. Aethelstan, perhaps one of the most compassionate of the Saxon Kings, ordered those who practised Wiccecraeft to be executed, but only if their activities resulted in murder.

Under Henry VIII’s Act of 1546, the penalty for conjuration of evil spirits was death and the property of the accused was confiscated by the King. However, this was in effect for only one year being repealed by Edward VI in 1547, and only one conviction under this Act is recorded. In 1563, the statute of Queen Elizabeth I was established, which also made death the penalty for invoking or conjuring an evil spirit, but those who practised divination or who caused harm (other than death) by their sorceries, were sentenced to a year’s imprisonment for a first offence. Subsequent offences could be punishable by death and in some cases the confiscation of property as well.

Even though laws against the practice of witchcraft had been established for hundreds of years, the first major trial was not until 1566 at Chelmsford, and was typical of the English style of witchcraft: no pact with the devil, no gathering at Sabbats, but simple and direct acts of maleficia and the introduction of witches’ familiars. It was an important trial for it set the precedent in English law for accepting unsupported, and highly imaginative, stories from children as evidence. It also accepted spectral evidence (sic), witch’s marks, and the confession of the accused.

(Elizabethan era witchcraft 2)

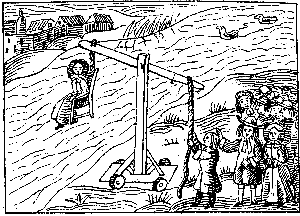

There are some very distinctive aspects to English witchcraft, which set it apart from its Continental and Scottish counterparts and which are worth noting. There was a relative lack of torture and witches were never burned in England. Traitors and murderers were burned; witches were hung. Of course, a traitor or a murderer could also be a witch, but this was actually quite rare. The torture used in England, when it was used at all, was typically swimming, pricking, enforced waking, and a diet of bread and water. Unpleasant, but when compared to squassation, being skinned alive, the strappado, the rack, and such delights as the thumbscrews and the iron maiden, hardly in the same class.

(Cucking stool)

The focus of English witchcraft was more towards simple, personal, acts of maleficia than a perceived conspiracy against the power of the Christian Church. As one of Britain’s foremost folklorists says: “Traditions of an organised, pagan witch-cult were never very plentiful in England, although they did exist occasionally, especially in the later years of the witch belief. They were never really strong, and after the end of the persecution in the early 18th century, they disappeared altogether.” (Christina Hole) This is interesting, because it has been suggested that the witch trials phenomena was largely inspired by the heretical Christian sects; this would seem to be born out by the type of accusations made in England, which were largely neighbour against neighbour rather than Church and State against an organised conspiracy of heretics.

What is also interesting is that it was commonly believed in England that if the bewitched victim could draw blood from the witch, then they would be cured and the witch’s power made ineffective. This belief has persisted in folk traditions to modern times. In 1875 at Long Compton, the body of an old woman, one Ann Turner, was discovered. She had been pinned to the ground by a pitchfork through her throat and across her face and chest had been carved the sign of a crucifix. James Heywood, a local farmer, had once claimed: “It’s she who brings the floods and drought. Her spells withered the crops in the field. Her curse drove my father to an early grave!”. Heywood maintained that the only way to destroy her power was to spill her blood and so after her murder, he was taken and tried for the crime. He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

In 1945, Charles Walton, a local labourer, set out one morning to do some hedging on nearby Meon Hill. That evening, his mutilated body was found in a field – pinned to the ground by his pitchfork, which had been stuck through his throat. There were cuts to his arms and legs, and local police were baffled as to the motive for the crime, and who the likely culprit might have been. But gradually locals began to talk about Mr Walton; they said he was a solitary and vindictive old man, who was concerned more with searching out the secrets of nature than in taking company with his neighbours. They said that he harnessed toads, using reeds and pieces of ram’s horn, and then sent them across fields to blight the crops. They also remembered that he kept a witch’s mirror – a piece of black stone polished in a mountain stream – concealed in his pocket-watch, which he used for weaving spells and seeing into the future. The police never discovered the culprit, but it was accepted locally that Mr Walton was murdered because he was a witch. His wounds were a result of the belief that a victim could be freed from enchantment if he or she were able to draw the blood of the witch. For more information about the witches of Long Compton, including the murder of Ann Turner, see ‘The Wiccan’ for Samhain 2008.

I could not leave English witchcraft without mention of that infamous gentleman, Matthew Hopkins; self-styled Witchfinder General. For all his fame, his activities were restricted to a geographically small area and a relatively short period of time.

Matthew Hopkins used the unrest of the Civil War to prey upon the fears of the common people. Little is known of his early life, except that he became a lawyer “of little note” and failing to make a living at Ipswich in Suffolk, moved to Manningtree in Essex; an area of Civil War tension.

With virtually no knowledge of witchcraft but armed with a couple of contemporary documents (including James I’s “Demonology”), Hopkins set himself up in business as a witchfinder. And a very profitable business it was too. At a time when the average daily wage was 6d, Hopkins received £23 for a single visit to Stowmarket, and £6 for a visit to Aldeburgh.

His approach was consistent: James I mentioned that witches had familiars and suckled imps; therefore, anyone who kept a familiar spirit or imp must be a witch. Bearing in mind the English partiality to keeping pets and you begin to see just how very profitable this technique could be. For example, Bridget Mayers was condemned for entertaining an evil spirit in the likeness of a mouse, which she called Prickears. Another (unnamed) woman was rescued by her neighbours from a ducking, where she confessed to having an imp called “Nan”. When she recovered she said: “she knew not what she had confessed, and she had nothing she called Nan but a pullet that she sometimes called by that name…”.

Hopkins moved from Essex to Norfolk and Suffolk and by the following year, had operations in Cambridge, Northampton, Huntingdon and Bedford, with a team of six witch finders under his control. “In Suffolk alone it is estimated that he was responsible for arresting at least 124 persons for witchcraft, of whom at least 68 were hanged.” (RHR)Hopkins moved too far too quickly however, and public opinion began to go against him. In 1646 a clergyman in Huntingdon preached against him and judges began to question both his methods of locating witches and the fees that he charged for the service. In 1647 Hopkins published a pamphlet called ‘Discovery of Witches’ in which he supported his methods in sanctimonious and pseudo legal language. It was to no avail however, for later that year he died, “in some disgrace” according to most authorities. Witchcraft legend has it that he was drowned by irate villagers in one of his own ducking ponds, but this has no recorded evidence to support it.

Moving away from England; Scottish and Continental witchcraft shared a great many similarities. Mary Queen of Scots and her son, James VI, were both educated in France and this ensured that continental attitudes towards witches were enshrined in Scottish law at the highest level. In fact the concepts of witchcraft were introduced into Scotland by Mary in about 1563. Before then, trials for witchcraft had been few and there were no recorded burnings of witches. In ‘The Encyclopaedia of Witchcraft and Demonology’ Rossell Hope Robbins says:

“Scotland is second only to Germany in the barbarity of its witch trials. The Presbyterian clergy acted like inquisitors, and the Church sessions often shared the prosecution with the secular law courts. The Scottish laws were, if anything, more heavily loaded against the accused. Finally, the devilishness of the torture was limited only by Scotland’s backward technology in the construction of mechanical devices.”

It is well known that James VI was an ardent prosecutor of witches, and it was under his authority that the Bible was translated to include the word ‘witch’ (Exodus 22:18) to provide Biblical sanction for the death penalty for witches. The original Hebrew word (kashaph) likely meant either a herbalist, diviner or sorcerer, but was definitely not a witch. In the Latin Vulgate (4th century version of the Bible) the word was translated as maleficos’, which could mean any kind of criminal although in practice often referred to malevolent sorcerers. Similarly, the so-called Witch of Endor, consulted by King Solomon: the original Hebrew was ‘ba’alath ob’, roughly ‘mistress of a talisman’. In the Latin Vulgate she became a ‘mulierem habentem pythonem’, ‘a women possessing an oracular spirit’. It was only in the version of the Bible authorised by King James that she became a witch.

By the time that James acceded to the English throne in 1603, his attitude towards witches had undergone a subtle transformation. In fact, he was directly responsible for the release and pardon of several accused witches and personally interfered in trials where he believed that fraud or deception was being practised. However, Lynn Linton writing in 1861 says of him:

“Whatever of blood-stained folly belonged specially to the Scottish trials of this time – and hereafter – owed its original impulse to him; every groan of the tortured wretches driven to their fearful doom, and every tear of the survivors left blighted and desolate to drag out their weary days in mingled grief and terror, lie on his memory with shame and condemnation ineffaceable for all time.”

But it was under Charles II that perhaps the most famous and enduring of Scottish witches was tried, and most probably executed (although records of her punishment have not survived). On four separate occasions during 1662, Isobel Gowdie of Auldearne testified that she was a witch and gave what Russell Hope Robbins describes as, “a resume of popular beliefs about witchcraft in Scotland.”. He says that Gowdie “appeared clearly demented” but that “it is plain she believed what she confessed, no matter how impossible…”.

From Gowdie are derived some of the concepts of today’s Wicca, including the idea of a coven comprised of 13 people. Gowdie said that the coven was ruled by a Man in Black sometimes called ‘Black John’. He would often beat the witches severely and it seemed their main tasks were to raise storms, change themselves into animals, and shoot elf arrows to injure or kill people. Coming as she does right at the end of the witchcraft persecutions it is difficult to establish how much of Gowdie’s confession is based upon real, traditional folk practices of Auldearne and how much she is simply repeating the standard accusations against witches.

The Coven of 13 is probably the single aspect of her confessions that does not appear elsewhere in records of witchcraft trials and my own inclination is that she was probably as genuine a witch as was ever taken and tried.

(Isobel Gowdie)

I commented earlier how terrifying it is to consider the impact that a single person can have upon the lives of so many people and provided examples of King James, Kramer and Sprenger, Matthew Hopkins, and Conrad of Marburg. Their modern day equivalents are no less terrifying. I have already mentioned Adolf Hitler; what about Stalin? his great purge in the period following 1936 saw charges of treason, espionage and terrorism brought against anyone who showed the least inclination to oppose him. Using techniques which would not have been out of place during the great witch hunts, Stalin’s henchmen enforced confessions and effectively exterminated any threat to his political power.

We could look too at McCarthy, whose fame for persecution was such that his name is now used to describe ‘the use of unsupported accusations for any purpose’. It is no accident that his activities were referred to as a witch hunt nor that Arthur Miller’s play about the Salem witch trials, ‘The Crucible’, was more a comment about McCarthyism than a comment about 17th century American life. Sadly, many examples of oppression and persecution still exist in our own century.

Our latter-day inquisitors play upon society’s fears in much the same way as Matthew Hopkins played upon the fears of the people during the Civil War. They continue use the gullible and the vulnerable in pursuit of goals that would horrify if they were ever truthfully articulated. Take for example the claims made by Audrey Harper, who achieved notoriety in Britain as an ex-HPS of a Witches’ Coven. This extract is from an article by Aries, which appeared in Web of Wyrd #5:

“Sent to a Dr Barnado’s home by her mother, she grew up with deprivation and social stigma. In time she becomes a WRAF, falls in love, gets pregnant, boyfriend dies, she turns to booze, gives up her baby and becomes homeless. Wandering to Piccadilly Circus she meets some Flower Children with the killer weed, and her descent into Hell is assured. By day she gets stoned and eats junk food; by night she sleeps in squats and doorways. Along comes Molly; the whore with a heart of gold who teaches Audrey the art of streetwalking. She flirts with shoplifting, gets into pills, and then gets talent spotted and invited to a Chelsea party, where wealth, power and tasteful decor are dangled as bait. At the next party she is hooked by the “group”, which meets “every month in Virginia Water”. She agrees to go to the next meeting, which is to be held at Hallowe’en.

Inside the dark Temple lit by black candles and full of “A heady, sickly sweet smell from burning incense”, she is “initiated” by the “warlock”, whose “face was deathly pale and skeletal… his eyes … were dark and sunken” and whose “breath and body seemed to exude a strange smell, a little like stale alcohol.” She signs herself over to Satan with her own blood on a parchment scroll, whereupon a baby is produced, its throat cut, and the blood drank. Following this she gets dumped on the “altar” and screwed as the “sacrifice of the White Virgin”. The meeting finishes with a little ritual cursing and she’s left to wander “home” in the dark.

Her life falls into a steady routine of meetings in Virginia Water, getting screwed by the “warlock”, drug abuse, petty crime, and recruiting runaways for parties, where the drinks are spiked -“probably with LSD” – and candles injected with heroin release “stupefying fumes into the air”; the object being sex kicks and pornography. She falls pregnant again, gets committed to a psychiatric hospital, has the baby, and gives it away convinced that the “warlock” would sacrifice it. Things then become a confusion of Church desecration, drug addiction, ritual abuse, psychiatric hospital, and falling in with Christian folk who try vainly to save her soul. For rather vague reasons the “coven” decide to drop her from the team, and she dedicates herself to a true junkie’s lifestyle with a steady round of overdosing, jaundice, and detoxification units.

The “warlock”drops by to threaten her, and she makes her way north via some psychiatric hospitals to a Christian Rehabilitation farm. She gets married, has a child which she keeps, and becomes a regular churchgoer. But beneath the surface are recurring nightmares, insane anger and murderous feelings towards her brethren. At the Emmanual Pentecostal Church in Stourport she asks the Minister, Roy Davies, for help. He prays, and God tells him that she was involved with witchcraft. An exorcism has her born again, cleansed of her sin. She gets bap- tised and has no more nightmares, becoming a generally nicer person. She becomes the “occult expert” of the Reachout Trust and Evangelical Alliance, and makes a career out of telling an edited version of her tale.

Geoffrey Dickens MP persuades her to tell all on live TV; “Audrey, to your knowledge is child sacrifice still going on?” To this she replies, “To my knowledge, yes.” After this the whole thing rambles into an untidy conclusion of self-congratulation, self-promotion, and self-justification; and for a grand finale pulls out a list of horrendous child abuse, which is shamelessly exploited in typically journalistic fashion, and by the usual fallacious arguments which links it to anything “occult”; help-lines, astro predictions in newspapers, and even New Age festivals.

And so we are left with a horrifying vision of hordes of Satanists swarming the country, buggering kids, sacrificing babies, and feeding their own faeces to the flock.”

As a direct result of people like Audrey Harper publicising their lies and fantasy, children in England and Scotland were forcibly removed from their homes and subjected to the type of questioning used by inquisitors and witchfinders.

In 1990, journalist Rosie Waterhouse commenting upon the Manchester child abuse case said: “After three months of questioning by the NSPCC, strange stories began to come out and other children were named. The way the children began telling ‘Satanic’ tales in this case is remarkably similar to the way such stories first surfaced in Nottingham (1987-9). As ‘The Independent on Sunday’ revealed last week (23/9/90), the Nottingham children began talking about witches, monsters, babies and blood only after they had been encouraged, by an NSPCC social worker, to play with toys which included witches’ costumes, monsters, toy babies, and a syringe for extracting blood.”

Believe it or not, the parents of these children had no access to them whatsoever. Why? Because our modern, scientifically trained, social workers believed that, “[the parents] would try to silence the children, using secret Satanic symbols or trigger words”.

By March 1991, senior Police spokesmen were publicly claiming that “police have no evidence of ritual or satanic abuse inflicted on children anywhere in England or Wales”. Scotland has a different legal system, which is why it was not included in the statement – not because the police have evidence there, for they do not.

When the Rochdale case finally came to court after the children had been separated from their families for about 16 months, the judge delivered a damning indictment upon those who were responsible for it and said: “the way the children had been removed from their parents was particularly upsetting.” He saw a video of the removal of one girl from her home during a dawn raid, and commented that, “It is obvious from the video tape that the girl is not merely frightened but greatly distressed at being removed from home. The sobbing and distraught girl can be seen. It is one of my most abiding memories of this case.”

A consultant clinical psychologist scrutinised the interview transcripts and audio records of the Orkney child abuse case (27th February 1991), and in her summing up said: “[the Social Workers] told the children they knew things had happened to them and were generally leading all the way. When the children denied things, the questions were continually put until the children got hungry and gave them the answers they wanted.”

The father of four of the children who were taken into care said: “At first I thought the allegations were laughable, but I found out how serious the police were…”. Just to remind you of the words of Gilles de Rais some 500 years ago: [the accusations] are frivolous and lack credit…”.

One 11 year-old described being asked to draw a circle of ritualistic dancers. He said: “They got me to draw by saying, ‘I am not a drawer. Can you draw that?’ It was meant to be a ring with children around and a minister in the middle wearing a black robe and a crook to pull children in.”

The boy said he had been promised treats such as a lesson on how a helicopter worked if he co-operated and was told that he could go if he gave one name. How remarkably similar to witch trials, where the victims were always pressed to name their accomplices.

Let us return briefly to Salem, where, in 1710, William Good petitioned for damages in respect of the trial and execution of his wife Sarah and the imprisonment of his daughter, Dorothy, “a child of four or five years old, [who] being chained in the dungeon was so hardly used and terrified that she hath ever since been very chargeable, having little or no reason to govern herself.”.

After reading this text again after more than 20 years, I can draw no different conclusion to that I drew in 1992: persecution has changed in only one respect in the last 2,000 years. In the 21st century we have far more efficient and effective tools to spread lies and propaganda than was available to our ancestors.

Julia Phillips

(This version was revised in 2013 and published in The Wiccan, Beltane 2013.)

Select Bibliography

There are a great many books on the subject of the European Witch Trials. This list a short bibliography of those to which I referred when writing this talk.

Bradford, Sarah Cesare Borgia (1981)

Cohn, Norman Europe’s Inner Demons (1975)

Ginzburg, Carlo Ecstasies: Deciphering The Witches’ Sabbath (1990)

Hole, Christina Witchcraft in England (1977)

Howard, Michael The Occult Conspiracy (1989)

Kieckheffer, Richard European Witch Trials (1976)

Larner, Christina Enemies of God: The Witch Hunt in Scotland (1981)

Larner, Christina Witchcraft and Religion (1985)

Maple, Eric The Complete Book of Witchcraft and Demonology (1966)

Radford, Kenneth Fire Burn (1989)

Ravensdale & Morgan The Psychology of Witchcraft (1974)

Robbins, Rossell Hope The Encyclopaedia of Witchcraft and Demonology (1984)

Russell, Jeffrey A History of Witchcraft (1980)

Scarre, Geoffrey Witchcraft and Magic in 16th and 17th century Europe (1987)

Stenton, Sir Frank Anglo-Saxon England (1971)

Summers, Montague (trans)Malleus Maleficarum (1986)

Thomas, Keith Religion and the Decline of Magic (1971)

Trevor-Roper, H R The European Witch-Craze of the 16th and 17th Centuries (1988)

Walsh, Michael Roots of Christianity (1986)

Worden, Blair (Ed) Stuart England (1986)

Encyclopaedia Britannica (1969 edition)

Collins Dictionary of the English Language (1980)

Newspapers: The Times, The Guardian, The Independent (Britain)