On November 4th 2023, Silver Circle held an event, ‘Honouring our Ancestors’, at the Autumn Gathering at Westhoffhuis in Lunteren. During the opening ceremony friends were invited to honour and remember beloved ones and ancestors.

The founder of modern witchcraft/Wicca Gerald B. Gardner was honoured with a presentation from Morgana, entitled: ‘Gerald Gardner & Indonesian Influences’. His book The Kris and Other Malay Weapons (1939) has become a classic, not only in Wiccan circles, and she was able to show various illustrations of not only the Kris but how they are made. She made mention of her visit in 2019 to Java & Bali under the guidance of Rich Eduard and Ivonne Keulen. (Read also Gerald Gardner and Indonesian influences, part 1).

Following the presentation Rich and Ivonne, from Stichting Aliran, continued the story with more about ‘The Kris & Javanese Mysticism’.

They had prepared a circle with a number of examples of Krisses and other ritual attributes.

Guiding us through a journey to meet ancestors or spirits of the Kris we were able to choose which Kris we felt attracted too. I chose a small one from Sulawesi, although I knew nothing about this region of Indonesia.

Tink wrote of her experience: “Today I went to SC Honouring our Ancestors Autumn Gathering after all and I’m glad I did. I’ve had a great day! It wasn’t a big group, but it was great to meet old and new friends and talk about all kinds of things.

In the opening ritual we were invited to honour our ancestors and loved ones on the other side of the veil. Morgana gave an interesting presentation about Gerald Gardner & his Indonesian influences, and his book ‘The Keris and Other Malay Weapons’.

In the break we enjoyed special-made spicy pumpkin soup and nice conversation. Then Rich and Ivonne of Stichting Aliran Tenaga Dalam continued on the theme with a fascinating workshop on the keris & Javanese mysticism. I don’t know a lot about it and perhaps it’s not really ‘my thing’, but I am definitely interested and always like to learn about other cultures. And knives attract me anyway. In the workshop we were allowed to make contact with a keris and through it with an ancestor. I had a wonderful, very special experience and shared it afterwards. It took away most of the fear for the ‘stille kracht’, although I’ll always stay cautious.”

On the Stichting Aliran website Rich describes in more detail the importance of ancestors and heirlooms:

Pusaka, Jimat and Keris: talisman and heirloom

“The literal translation of the word pusaka is heirloom. Many Indonesian families in the Netherlands cherish an heirloom from the Dutch East Indies as one of the few concrete tangible memories of a life far away and long ago. It connects the family and their history. The pusaka object can be a keris or another object that has a valuable meaning, such as a pair of wayang golek dolls, jewellery, coins, but also a photo, a letter or an old teddy bear can be a pusaka. The value of the pusaka lies mainly in the meaning the object carries, due to its long history within the family. The pusaka is often well preserved and is passed on to someone from the next generation who has an affinity with it. Sometimes the stories associated with it and its traditional uses are also preserved.

Indonesia also has a long tradition of family heirlooms. Heirlooms enjoy great prestige because they can be many generations old. Because the pusakas have been used from generation to generation, this frequent use can be felt on the object as an attached energy field. The pusaka is then appreciated precisely because of the energy attached to it and has then become a jimat (talisman). It has now become an instrument with which potential contact can be made with an ancestor. Its powers are invoked when the item is used again.”

We finished the day by regrouping in the larger Circle and thanking the Spirits of the Land for their presence and bid them farewell.

The inner working with the Kris reminded me of some of the inner journeys we make – but also the inner connection we have with our own ceremonial dagger/knife, the Athame.

When I was compiling and sorting the material I had for the first part of this presentation I started taking more notice about my connection to my Athame. Certainly after the visit to Bali & Java with Rich & Ivonne in 2019 I became much more aware of the similarities of the Kris and Athame. Previously, much of my experience of the Athame has been led by my own intuition, although there were some instructions of course about how it should look, what it should be made of etc.

Although we see the Athame referred to as a ‘creature of steel…’ many people use wood, or other types of metal (silver, iron, bronze) these days. The Kris blade is traditionally made of iron, or ‘meteorite nickel’ but it is also a ‘creature of steel’. Today stainless steel is used.

As a ‘creature of steel’ let us look at the esoteric background of first, the Athame. As a ritual tool it is rich and multi-faceted, drawing from a variety of historical, cultural, and symbolic sources.

Blades have been used in magical and religious ceremonies since ancient times. In various cultures, knives and daggers were considered powerful tools for both mundane and spiritual purposes. They were often used to draw protective symbols, perform sacrifices, and delineate sacred spaces. The Athame’s use in modern Wicca can be traced back to Western Ceremonial Magical Traditions. Texts such as the Key of Solomon (a medieval grimoire) describe the use of ritual knives for specific magical operations, including drawing circles and invoking spirits. In Alchemical and Hermetic traditions, blades were symbolic tools used to represent separation and transformation processes. The Athame can be seen as an extension of these practices, symbolizing the ability to cut through illusion and uncover deeper truths.

In many traditions, the Athame is associated with the element of Air, representing intellect, communication, and the power of thought and discernment. In some Wiccan traditions, however, it is instead linked to Fire, symbolizing willpower, passion, and transformative energy. This duality highlights the Athame’s role in both mental and spiritual processes.

In the ritual ‘Cakes & Wine’ the Athame often embodies the masculine principle, or yang energy, complementing the feminine principle, or yin energy, represented by the chalice. This balance is crucial in many Wiccan rituals, emphasizing harmony and the union of opposites.

When used to cast and close the sacred circle, one is creating a protected space for ritual work. This act of delineating sacred space is a fundamental aspect of many esoteric traditions, ensuring that the ritual area is consecrated and protected from external influences.

The Athame is a tool for directing magical energy. When performing rituals, we use it to focus our will and intent, channelling energy towards specific goals, invoking deities, or banishing unwanted entities.

In addition to practical uses, the Athame is employed in various symbolic actions within rituals. These include consecrations, the symbolic cutting of cords (representing the severance of unwanted connections), the symbolic opening and closing of gateways between realms, and the drawing of magical symbols in the air.

On a deeper psychological level, the Athame can represent inner strength, clarity of thought, and the ability to cut through illusions. It is a symbol of personal power and spiritual authority, reflecting the journey towards self-awareness and mastery.

As Gerald Gardner pointed out ‘The Athame is the true Witch’s Weapon’ and as such embodies and embraces all the elements including Spirit and the connection to our Higher Self. In this sense it links us to our Ancestors who have trodden this path and continue to guide us.

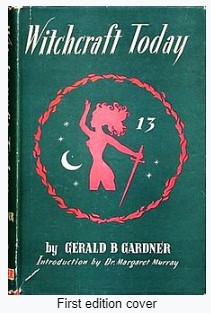

Gardner’s description and use of the Athame (Weapons) primarily appear in his books Witchcraft Today (1954) where he briefly mentions the Kris in relation to the Athame, noting the influence of Eastern magical practices on Wiccan tools. He admired the Kris’s craftsmanship and spiritual significance, which then inspired the use of the Athame in Wicca.

In The Meaning of Witchcraft (1959): Gardner elaborates on the magical and symbolic aspects of ritual knives, including the athame. He draws parallels between the Kris and Athame, emphasizing their roles in focusing and directing energy.

Gardner’s integration of these tools into his writings helped shape modern Wiccan practice, blending elements of Eastern and Western magical traditions to create a unique and cohesive system of ritual tools and symbolism.

In the book Gerald Gardner – Witch by Jack Bracelin (1960) there is a long account by Gerald of his experiences in Malaysia and where he retells stories of the Kris.

He writes: “The kris, it seemed, was considered by everyone – collectors, weapons experts, museum curators – as merely a weapon, simply the characteristic form which the dagger had taken in these parts. And yet, he noticed, the blade was treated with respect by the Malays. It came in distinctly different varieties. Some kris at least had distinctly talismanic virtues. Many tales of magical kris and their makers were told.”

The Kris and the Athame both have connections to traditions of ancestor worship and veneration, though they emerge from different cultural contexts and practices. The Kris (or keris) is a traditional dagger from Southeast Asia, and is particularly associated with Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines. Its wavy blade and rich symbolism make it a significant cultural and spiritual artifact. It is often considered a powerful heirloom, passed down through generations. It is believed to carry the spirit and blessings of the ancestors, making it a vital part of family heritage.

Having its own spirit and magical properties it is used in various ceremonies for protection, blessings, and communication with the spiritual realm. It is used in rituals to honour ancestors, seeking their guidance and protection. It is also used in rites of passage, such as weddings and funerals, to invoke ancestors and ask for their blessings.

And as we saw in my description of a Kris being blessed in Bali (2019) it is custom-made, reflecting the personal and spiritual characteristics of its owner. The process of crafting and ‘activating’ a Kris involves rituals to connect it to the Spirit.

In the ritual to consecrate the 3 Krisses offerings and prayers were made to ancestors and deities. This consecration enhanced its spiritual potency and connection to the ancestral realm.

Whilst the Kris & Athame have similarities both in looks (both have a double-edged blade) and usage there are nuances.

This is most noticeable when we look and compare the masculine and feminine aspects of both weapons. The masculine aspects of the Kris are often seen as a symbol of power, strength, and authority, traditionally carried by warriors and leaders, both men and women. This association with protection, defence, and assertiveness aligns with masculine energy.

Concerning feminine aspects, the wavy, sinuous lines of many keris blades can be seen as embodying feminine qualities of fluidity, grace, and subtlety. In some cultures, the Kris is believed to possess a nurturing and protective spirit, guarding its owner and bringing harmony and balance. These nurturing and protective roles are often associated with feminine energy.

In rituals, the Kris may play roles that emphasize feminine aspects, such as fertility, creativity, and connection to the earth and the spiritual realm.

However, the Kris is often regarded as having a dual nature, embodying both masculine and feminine qualities. This duality reflects the balance and harmony between opposing forces, a common theme in many Southeast Asian spiritual traditions. Each Kris is believed to have its own unique spirit, which can be either masculine or feminine, or a blend of both. The specific characteristics of a Kris’s Spirit depend on its craftsmanship, history, and the rituals performed during its creation and consecration.

It’s symbolism is versatile and can change depending on the context in which it is used. In some ceremonies, it may emphasize masculine attributes, while in others, it might highlight feminine qualities. It cannot be strictly categorized as masculine or feminine; instead, it embodies a dynamic interplay of both energies. This duality reflects its deep spiritual significance and its role as a powerful cultural artifact.

Understanding the Kris requires an appreciation of its rich symbolism, historical context, and the cultural beliefs surrounding its creation and use. It stands as a testament to the nuanced and multifaceted nature of spiritual and cultural symbols in Southeast Asia.

Ironically Gerald Gardner’s interest in the ‘Kris and other Malay Weapons’ has helped to keep the heritage of the Kris alive. His book is still regarded as a classic. Reading between the lines of his other seminal works, particularly the book Gerald Gardner – WITCH by Jack Bracelin, we can see how his experiences in Malaysia, Borneo, Sri Lanka pointed to an animistic approach in his Wicca practice and his love for ancestral veneration.

In any event my own journey with the Kris has enriched my understanding and working with my Athame. At every Circle, at every Full Moon I remember, when calling the Quarters or blessing the Salt & Water, or celebrating Cakes & Wine my dedication and commitment to the Craft. My Athame is indeed my ‘true Witch’s wonder-working weapon’.

APPENDIX

As I mentioned in my article in the book Gerald Gardner – WITCH by Jack Bracelin (1960) there are many references to Gardner’s research in Malaysia concerning the Kris. In this excerpt, it is also interesting to note his own experiences and contact with local people. His interest was not purely academic – his curiosity about folklore and folk-magic was much deeper.

Excerpt from Chapter 6 THE MAGIC OF MALAYA

about The Magic of the Kris

His (Gerald’s) interest in weapons and his new, close friendship with the Malays inevitably drew him to the study of the Kris – the wavy dagger which has been brought back by so many former residents in Malaysia, but about which, he noted with surprise, there was virtually no literature, certainly no book. The kris, it seemed, was considered by everyone – collectors, weapons experts, museum curators – as merely a weapon, simply the characteristic form which the dagger had taken In these parts. And yet, he noticed, the blade was treated with respect by the Malays. It came in distinctly different varieties.

Some kris at least had distinctly talismanic virtues. Many tales of magical kris and their makers were told.

Was there really a magical, amuletic kris? Nonsense, said the planters, the civil servants, the museum people. Gardner was far too full of ideas; he thought that everything had a meaning which it did not necessarily have. But, he argued, was it not necessary to ask the Malays something about their weapons, about their varieties, their history? No, everything that was known had been written by Raffles – and Raffles’ name was sacrosanct.

But Gardner knew better. He arranged for Cornwall to invite some of his Malay friends, to show him their dances, their knives, tell him the tales of old. Raffles had only mentioned ordinary kris in his book, which everyone quoted, but had never read through. And they came, bringing old weapons, wrapped in cloth and disguised, because they were not now officially allowed to carry them.

During this evening girls performed dances based on the temple dances of Hindustan, and there was a purely Malayan Kris-dance and kris-fencing. Gardner noticed the respect with which the blades were treated.

Then the old people would sit and talk, and tell tales; tales of Sembelan Poluh Sembelan, the magical spear. This was tied to the central beam of a house in the neighbourhood. Once a year it was taken down for cleaning, and then replaced. It was possessed by a hantu – a spirit – and it must not be allowed to work loose. The hantu caused it to rattle when any member of the family was going to die: a story reminiscent of odd omens associated with so many old houses in Britain. …

In between the dancing and the singing, the feasts and the expeditions to see strange weapons and hear of stranger tales, Gardner heard tantalising tales of the Kris Majapahit, the most curious of all magical weapons. Over a period of twenty years in Malaya, Gardner followed the clues to the Majapahit and other unusual kris, and became the world expert on every variety of the weapons. His beautiful home housed a magnificent collection of oriental weapons, many of which went to the Raffles Museum in Singapore.

Today, the British Museum has a Kris Majapahit, and another magical variety – the Kris Pichit, a tiny talismanic dagger – presented by Gardner. Although the Singapore Museum had four majapahits, they had no idea what they were. The Majapahit was almost a legend; many people did not believe that they really existed at all. By dint of considerable discussion and proving points, one by one, Gardner was able to establish their actual identity.

These weapons, whose powers are known and believed by Malays of all stages of culture, have small figures, sitting or standing, on the hilt. … The kris contains a hantu – a spirit, which has in some way become attached to it. These daggers are very old; they are not wavy like other varieties of kris. Small, slender and thin, the iron of which they are made is black. The handle and blade are all in one, and the handle is a figure of a man or a woman. Many Malays said that the larger figures are male, the smaller female. They might represent some ancient gods or spirits which were the titularies of the enchanted blades.

Gardner pursued his search.

The Malays agreed that the majapahits were very poisonous.

The kris of the Majapahit type brings luck to the owner, and the hantu may preserve him against dangers of all kinds. But they are only lucky if the spirit likes the owner. “You must treat them with respect”, Gardner noted. …

Like other pioneers, he [Gardner] proved his results only against stiff opposition. In one museum, when he spoke of the kris majapahit, an official flatly refused to believe in the vast complex of folklore about the little dagger: “Why do you not ask the Malays who work in the museum?” said Gardner. “Even the doorkeeper could tell you a great deal about what all Malays believe about this most important of their cultural objects”. But this is not always the way in which the academic mind works, and Gardner’s unorthodoxy in squatting down with the natives and learning about their ways was looked upon askance. …

Some of the majapahits, the Malays confided in Gardner could draw fire. If a house, for instance, was burning, and the kris was pointed at it and moved in an arc, the fire would follow the movement of the dagger and leave the house. These powers, as in many other forms of magic, must be used only in cases of real need. If a fire were lit just to test the kris, it would not do its work: and the hantu within it would bring bad luck upon the experimenter. Nobody would play about with spirits, or challenge them.

Gardner himself found that a Kris could be your friend. One protected him from robbers:

The little dagger certainly did the trick for him: “So I betted on the superstition of the people. In all countries robbers are the most superstitious of people. I spread the yarn of what I carried. Anyhow, though several attempts were made to get me while carrying money, none came off. Several times there were bad floods, and ambush parties waiting for me were cut off and nearly drowned. At last, I was reckoned ‘unlucky’ to meddle with – and generally got the job of fetching the pay, which I liked, as it meant a trip to town at the Company’s expense”.

Gardner embodied some of his investigations and conclusions in papers which he wrote for the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society[i]; which gained him a good deal of academic recognition when they were published. Meanwhile, he worked upon his magnum opus – Kris and Other Malay Weapons, which finally established him as the world authority. This is still the standard work on the subject. …

Malays said that a magical kris should be kept tightly sheathed at all times when not in use, and pointing upwards or downwards – otherwise the evil influence would do harm and cause sickness. “How much the modern Malay believes I cannot say; more than he admits, I believe. That older people believe in it I had proof, when a highly educated Malay lady screamed and nearly jumped out of her chair, because a sheathed kris majapahit I was showing inadvertently pointed at her”. If enlightened Westerners cannot break a looking glass without at least a momentary anticipation of seven years of bad luck, it seemed not impossible that in Malay many might not be prepared to risk illness or death from the magic knife. Attempts to explain the origin of the belief in pointing to produce death or disease are many, and Gardner mentions some of them. “Malays have a much-feared form of sorcery, tuju – pointing out a victim to a spirit of evil, or setting the spirit at him. The pointing is usually done with the finger, though I have heard of a human bone being used. Perhaps the idea of pointing the kris is in setting the spirit of the kris at him”.

… As a part of the Malay heritage, Gardner felt, it should be more widely worn. …

Many legends surrounded the extraordinary Kris Pitchit, Gardner found. If he had seen only eight majapahits, only three of the reputedly miraculous Kris Pitchit had for long come his way. Over the years he was to find many more; one belonged to a resident of Kedah, one was in his own possession, and the third was lent by him to the Singapore Museum. They are all very thin, with blades damascened. Their special feature, from which they take the name pitchit (squeezed) is the round depressions on either side of the flat of the blade, which appear slightly raised on the other side, exactly as if someone had taken a strip of clay and squeezed it between the tips of his fingers. It could have been made by taking a red-hot blade, and squeezing it out with tongs shaped like the finger tips. The finger-marks seemed to have been made in the process of manufacture, he observed, as the damascening follows through the marks.

… Invulnerability, like drawing fire away from houses or killing by magic, seems to be successful in the Malay belief, only under “genuine” circumstances. It cannot be reproduced experimentally. This may point to the presence of the emotion-concentration theory. Magic, it is held, works at least partly because of the amount of emotional force which the individual puts into it.

But it only works in circumstances of actual necessity, not when you experiment or show off. …

His close contact with the magical thinking, the legends and the folk-practises of Ceylonese, Dyaks, Saki and Malays, as well as his reading of the work published by more and more Western investigators, was convincing Gardner of the necessity for a new attitude towards the whole question of the supernatural. As a scientific worker, he was bound to seek and if possible to find a rational explanation for the wonders which were reported from all sides. Legends, when they took very similar forms in various countries, were generally attributed to culture-drifts: stories following trade-routes, and so on.

Yet, at the same time, he was continually coming across instances of beliefs which were misinterpreted or ignored by more conventional workers. How much more priceless material, he wondered, had been shrugged off – both here and elsewhere – because it was not possible to find an explanation in the light of contemporary knowledge? Further, he noted that while the Malays and other Asian people were fond of inexact and escapist thinking, they were so often correct in matters of feeling and understanding.

His later experiences, with the witches of Britain, convinced him that magic did work, probably by elevating the concentration faculties of the mind in a way which made it impossible for it to be reproduced experimentally. Unlike most people with a pet theory, he had three frames of reference: the Oriental magicians, the spiritualists in London, and the followers of the Craft of the Witch in Britain. All of them, he is convinced, have something in common, something which we call magic, but which one day may find recognition (just as the Kris Majapahit, which ‘did not exist’) had eventually to be acknowledged through painstaking study and experience.

Some magical tales, at least, may be works of pure fiction. Others, again, could be caused by faulty observation of events, or distortion in transmission from one person to another. Behind many such accounts, however, Gardner was sure that there was something. So he collected unusual stories of the occult.

[i] From the Journal Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. XI, Part 11, 1933, where Gerald Gardner writes about the Malay Kris

References:

With thanks to Rich Eduard & Ivonne Kreule / Stichting Aliran for the photos and image of a card from the deck of cards – ‘Kaarten van Stille Kracht’.

Gerald Gardner – WITCH by Jack Bracelin, 1960. Octagon Press, 1990 I-H-O books Latest edition Publisher : Pentacle Enterprises (1 Sept. 1999) ISBN 9781872189086

https://www.jstor.org/journal/jmalayanras (Journal, Malayan branch Royal Asiatic Society , Vol XI, 1933 https://www.jstor.org/stable/41559813

Pusaka, Jimat, Keris: https://www.aliran.nl/aanbod/workshops/pusaka-jimat-keris/

Athame – damascus: https://www.etsy.com/listing/1113975447/custom-handmade-damascus-steel-knife

Kris – damascus: https://indosphere.medium.com/keris-the-sacred-daggers-of-indonesia-355326550e8d

Books, Leiden, 2009

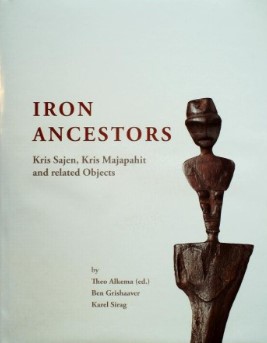

IRON ANCESTORS.

KRIS SAJEN, KRIS MAJAPAHIT AND RELATED OBJECTS.

Alkema, Theo (text); Grishaaver, Ben (photography); Sirag, Karel (line drawings).

This important monography focusses on the all-iron kris with an ancestor as its hilt, amulets rather than weapons. This first ever publication on the subject entirely devoted to these time-honoured heirlooms is based on the collection of the National Museum of Ethnology (Leiden, the Netherlands) and on a private collection of great quality and quantity. Theo Alkema’s ‘Iron Ancestors’ is enhanced with 288 illustrations by top-photographer Ben Grishaaver and with 27 exquisite drawings by the artist Karel Sirag.

https://www.academia.edu/23350430/THE_JAVANESE_KRIS (PDF)

ISAÄC GRONEMAN – THE JAVANESE KRIS, Preface and Introduction by David van Duuren.