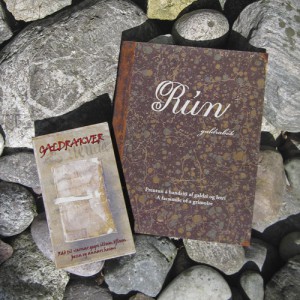

Rún, magic grimoire

Strandagaldur ses – Galdrasýning á Ströndum, Hólmavik 2014. ISBN 978-9979-9584-7-5

133 p. KR 3.600 (ca. € 25)

Galdrakver (Book of Magic) Lbs 143, 8vo

Landsbókasafn Íslands – Háskólabóksafn, Reykjavik 2004; 2nd ed. 2010. ISBN 9979-800-40-2 (I-II)

64 & 215 p. KR 6.950 (ca. € 48)

Unless one succeeds in raising the dead to interview them, it is impossible to ascertain how much credence writers, compilers or copyists of grimoires* themselves attached to the magical symbols, charms and cures they mentioned. It has been said that the books may have been written as fiction, and are best to be considered as a literary genre. According to that view, a grimoire was meant to amaze and amuse, more or less like today’s magic shows or fantasy movies, or to give enjoyable shivers like a horror story. Or perhaps to let people dream of a different reality where everything is possible, some land of Cockaigne. Not so much as a serious manual.

One possibility doesn’t exclude the other: different people have different ideas and needs. Just like today, some may have taken the magic seriously and others less so, while many will have been not too strict in what they believed or didn’t believe, and were quite happy to give things a try if it wasn’t too creepy or too much of an effort.

The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft certainly knows how to put the horror potential of traditional magic to good use for entertainment and publicity. Their ‘necropants’ are famous all over the world. But they also provide information on Icelandic history and folklore (although most of it in Icelandic), both as articles on the website and books from the webshop. I was especially interested in their grimoires, and ordered Rún, magic grimoire and Galdrakver (Book of Magic).

Rún starts with a collection of magical alphabets, followed by ‘staves’, or symbols to be carved in wood or drawn otherwise. For example: “A stave to protect sheep: To prevent the tide flooding your sheep, carve this stave on the horn of the oldest ram.” There is an instruction to make a ‘Witch riding stave’, and one to make a ‘Looking Glass’ in which you can see all over the world. The book also gives some untranslatable riddles, and advice about herbs and stones.

The main part of Rún is a facsimile reproduction of a handwritten grimoire. In the back of the book an English translation is given, and some background information. The manuscript was written in 1928 for Magnús Stindgrímsson, a farmer who was also an active community member and one of the founders of his local library. Apparently his 14-year old daughter Borghildur copied it from an unknown source. A comparable manuscript in the National Library in Reykjavik (Lbs 4375 4to) states to be copied from a manuscript from the year 1676.

In comparison with what I seem to remember from similar texts, what strikes me is that when something has to be written in blood, the Icelandic sorcerer/ess as a rule does not use the blood of a mole or a white dove or other animal, but his or her own blood, “from the life vein of your left hand” or “from the small toe of your left foot, the little finger of the right hand, and the right breast.” (Still, not all Icelandic magic is suitable for vegans.)

Galdrakver consists of two small books (14 x 8,5 cm) in a case. The first volume is a facsimile of a 17th century handwritten book of magic. The second volume gives a literal transcription of the text, and translations in modern Icelandic, Danish, English and German. This book contains so-called epistles, symbols, spells and prayers that were supposed to give some kind of protection, and sometimes included a story of how those powerful words and symbols came to be known to mankind.

There are for instance three drawings of three connected circles, “which God sent with one of his angels to Pope Leo, which he was to bring to King Charlemagne for protection against his enemies”. Of every one of the nine circles is specified what it is good for, or from what it protects, e.g. “from the rage of enemies, so that when they lay eyes upon thee their minds are seized with such terror that they become powerless and collapse” (3rd circle of the first set).

I noticed that the same symbols are given twice in Rún, first as “Charlemagne’s aid circles” but without specifying the different kinds of aid, and later on, the drawings barely recognizable, as “The circles of Charlemagne: first ‘helm’, second ‘rune’, third ‘rose’. These are highly powerful protective staves against everything evil, both on land and sea.”

Books like these are fascinating reading material and deserve to be studied. They give an impression of the hardships and fears of the people who wrote or used them. A comparison between books from different times and/or places could provide insight in how information was passed on without the help of mass reproduction devices like the printing press, photocopier or computer. But reading grimoires can be just good fun, too.

* I use the word ‘grimoire’ here in the sense of the Dutch ‘toverboek’, meaning any book that gives magical instructions, recipes, symbols, incantations etc., regardless of the ‘colour’ of the magic or the social class of the intended readers.