Wudewasa

Matthew Cowan (artist) Bruce E. Phillips & Andreas Bee (texts; both in English and German)

Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg Berlin 2016

ISBN 978-3-86828-700-4, 96 pag. € 24,90

Accidentally I came across this book with a word as its title that looked strange and yet vaguely familiar. I didn’t immediately recognize its meaning. But when I opened the book, the photographs made instantly clear that the artist let himself be inspired by folk traditions of dressing up in foliage, straw, sheepskins and the like, to symbolically enact encounters of mankind with nature spirits, or spirits of wilderness. And indeed ‘Wudewasa’ refers to the Wild Man, who can be the Green Man of vegetation but also the spirit of cattle, or of nature in general.

Matthew Cowan (yes, Cowan…) was born in New Zealand. Before turning to the arts, he studied psychology. Around that time he and his friends wanted to be in a band, “but none of us were really musicians, so we became Morris dancers,” he tells in an interview at the end of the book. Living in New Zealand in the 1990s they didn’t know much about Morris dancing, so they relied mainly on their own imagination. They started performing under the name of Green Man Morris and had a great time.

When Cowan came to the UK in 2009 to research European carnival traditions, and especially the costumes for traditional English dance, he followed Morris dancers throughout the country to take photographs. It struck him that folkloristic events attracted huge crowds, but at the same time were treated with derision and ridicule. This aroused his interest in the subjective narrative experience of such performances: “What is it that people are looking at and what stories are people telling themselves when they are looking at these events of ritual dance? (…) In their own minds do they know what it is that they are watching? Do the performers even know the origins of what it is that they are doing? I found that you could ask 10 different people and have 10 different stories (…) This is also the case with my artwork. The work I make is not the performance, it is the meaning that observers take from it.”

He also discovered the idea of the Wild Man. Depictions of the Wild Man (usually as Green Man) can be seen on buildings or in churches. The body of the Wild Man is covered in hairs or leaves. This character dates from at least the Middle Ages and lives on in diverse folk traditions. He is only half human, i.e. half civilized, and his non-human part often transgresses the norms of society. Wild Men characters and people wearing costumes during carnival can show lewd behaviour that wouldn’t be acceptable under normal conditions. They have something devilish about them and they may be frightening, but they can’t be called bad or evil – or good for that matter, for they represent the world of nature, which has no notions of morality.

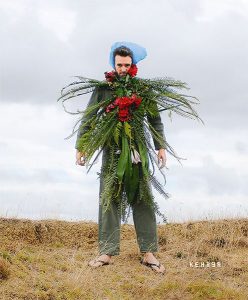

The Wild Man inspired Cowan to a series of ‘Wild Man’-costumes of his own devising. Wudewasa contains the essay ‘I am another’ in which Andreas Bee explores the principle of masking, and the interview with Bruce E. Phillips I already referred to, but it consists mainly of photographs of the artist, standing with his feet apart and arms slightly away from his body, wearing enormous ‘beards’ of flowers, ferns, grasses… Or a bodysuit completely covered in red and white ribbons with Morris bells, or chicken feathers, or synthetic wigs. There are also two Krampus-type costumes made out of plastic drinking straws, one white and the other black, called ‘Strawdevils (Day & Night)’, as well as two ‘Equinox Men (Spring & Autumn)’ whose ‘fur’ consists of strips of red/yellow and black/green orientation tape. Those reminded me of the modern shamanic dress made by Daan van Kampenhout out of plastic bags, which I saw years ago at the exposition on shamanism at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam.

There is a delightful kind of humour in this art. The use of a nowadays so ubiquitous material as plastic evokes a refreshing alienation, as well as a sense of living ‘authenticity’ that many modern masks, costumes or ritual objects seem to lack. But of course that is my perception; others may find other meanings. When I showed the book to my mother, the first thing she remarked was: “Why is he wearing a plastic bag on his head all the time?”

You can read more about Wudewasa and Matthew Cowan’s other projects on his website:

https://www.matthewcowan.net/flowerbeard.html